By Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

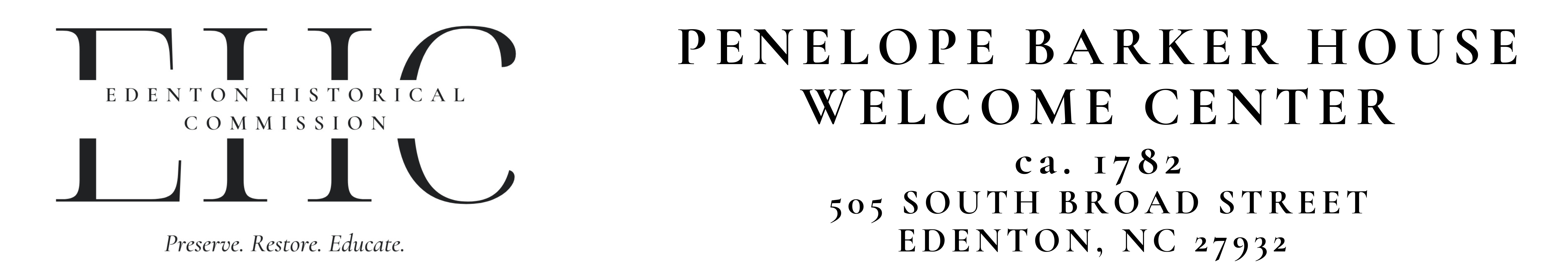

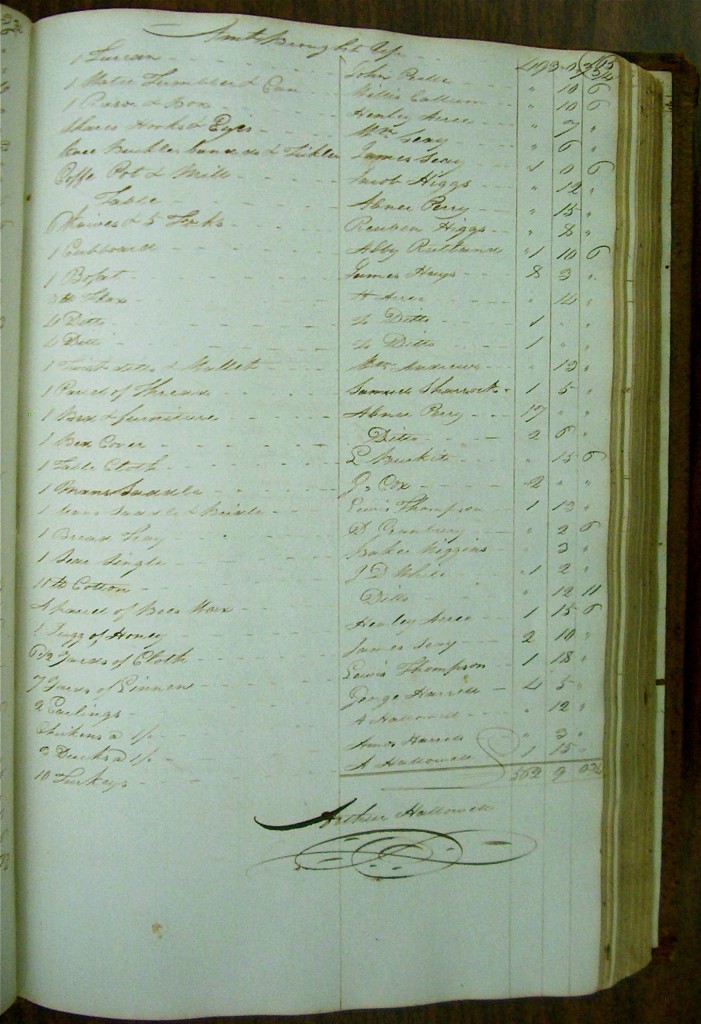

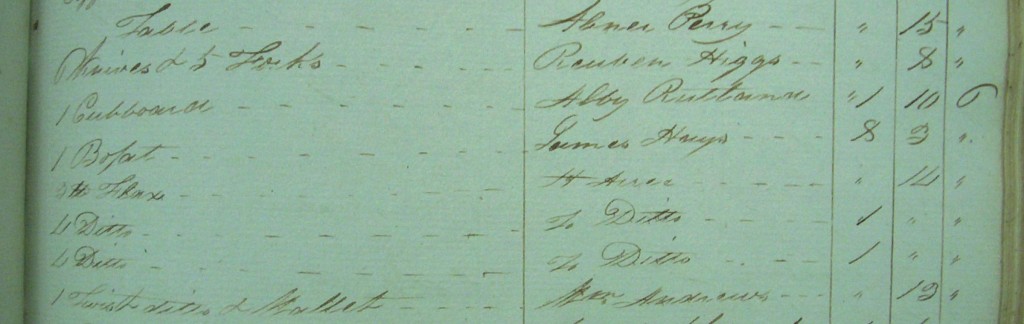

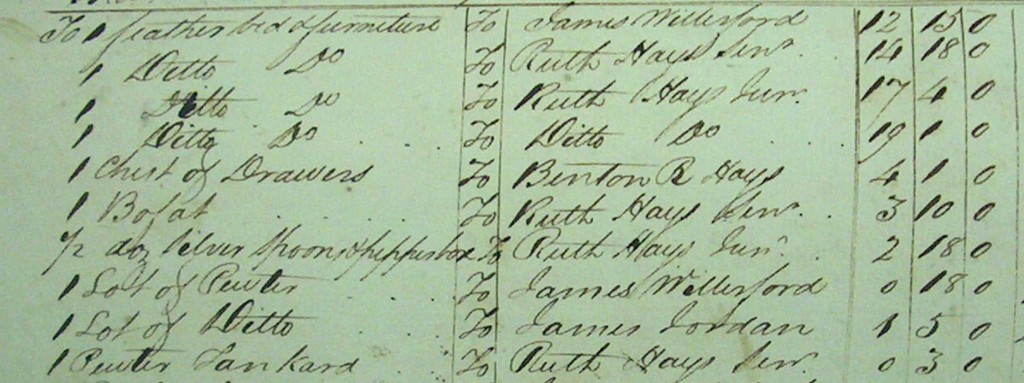

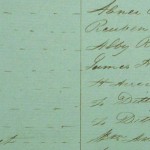

A recent article offered two insights into the history of the William Seay china press with secretary drawer currently in the collection of Historic Hope Foundation. The first involves the authors’ detailed examination of William Seay’s incised signature on the upper inside edge of one of the press’ case drawers. They go into great detail comparing Seay’s incised signature on the drawer to Seay’s signatures on the indentures of two of his apprentices, signed in 1774. They correctly conclude that all were written by the same individual, self-professed house joiner, William Seay (Fig. 1, Incised William Seay signature on Hope press). They especially emphasize the formation of the “W” in William in each of the signatures, noting how all examples are formed in the same way, and all include the same distinctive flourish at the beginning of the “W,” as well as distinctive loops at the bottom of the “W” in each signature.1 The “S” used in Seay also matches the “S” we found in Seay’s name written inside the built-in press in the Pugh-Griffin house (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Fig. 291). This is important as it demonstrates that William Seay carefully maintained the same method of writing his signature from the mid 1770s until near the end of his life around 1812.

The second insight involves the initials set in the roundel of the tympanum of the Hope press. Seay’s convention for his memorial pieces was to use two equal-size initials of the first and last names for a single owner. For a husband-wife piece, he used three equal-size initials of the first name of the husband, first name of the wife, and last name of the couple. This three-initial approach is seen on some needlework of the period. A number of documented examples remain of this same method being employed by regional silversmiths to memorialize a couple’s marriage.

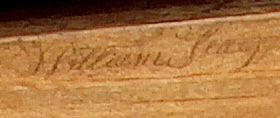

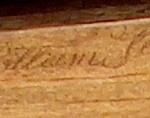

The Hope press initials likely represent the names of the press’ original owners just as the examples marked with the initials “WH” represent their ownership by Seay’s wealthy client, Whitmell Hill. The fact that there are three initials on the Hope press signifies that the press probably was constructed to memorialize the marriage of the original owners. Seay also employed three initials on the front of MESDA’s cellaret with the initials “JSS”, which commemorated the marriage of Halifax planter, Captain James Smith, to his fifth wife, Sarah Hill (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Figs. 183 and 185). Previously, the initials on the Hope press have been interpreted as “CRJ” or “CRT”. The authors of the article, however, present a persuasive case that the initials are actually “PRT”. They discuss the fact that each of the three initials on the Hope press display a “striking similarity” to the corresponding letters illustrated in an alphabet chart entitled “Flourishing Alphabet” in George Fisher’s, The Instructor, first published around 1731 and republished numerous times in Great Britain and the Colonies.2 All three letters on the Hope press are formed in exactly the same way as the corresponding letters in Fisher’s “Flourishing Alphabet”. The unconventional formation of the “P” both on the press and in the chart is especially enlightening. Seay also appears to have used a second alphabet chart from Fisher’s book entitled “An easy Copy for Round Hand” as inspiration for the “WH” initials on the furniture he constructed for Whitmell Hill and members of Hill’s family (Fig. 2, Alphabet chart from The Instructor) (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Figs. 86, 87, 98, 101, 106, and 117). Seay’s use of a second chart from the same book adds great strength to the interpretation that the letters on the Hope press are “PRT” and that they are based on letters found in the “Flourishing Alphabet”. Seay appears to have referred back to Fisher’s “Flourishing Alphabet” when he designed the initials on the Smith cellaret.3

The question now becomes who were “PRT”, the original owners of the Hope press? We conducted a search of census records for the years 1784-1787, 1790, 1800, and 1810 for Bertie, Halifax, Hertford, Martin, and Northampton Counties, the only counties where Seay patrons have been identified, for a male with the initials “PT”. A search was also conducted of grantor and grantee indexes of deeds recorded in these counties during this period. Since this piece was most likely constructed by Seay to commemorate a marriage, the “R” would represent the first letter of the given name of the bride.

Males with the initials “PT” proved to be quite rare in the census and deed records examined. Only five males with the initials “PT” were identified as potential owners of the press. Three were found exclusively in Halifax County. Peter Turner is listed as a resident of Halifax County in the censuses of 1784-87, 1790, and 1800. He was the son of William Turner and is listed in his father’s Halifax County will dated January 10, 1786.4 Peter Turner was a constable for District 9 in Halifax County as early as 1785. He served on Halifax County juries in 1796 and 1797. His will was written and signed on January 29, 1806, and was probated in February of that year. In it, he lists his wife as Susannah.5 Peter and Susannah Turner’s initials do not match the initials “PRT,” and there is no other evidence linking the Turners to William Seay.

The second potential “PT” in Halifax County is Peter Tuttle, who is listed in the Halifax County censuses of 1790, 1800, and 1810. He is listed in the Halifax County will of Robert Carter, dated December 25, 1797. In it, Tuttle is listed as Carter’s son-in-law. Carter’s wife is listed as Sarah Carter.6 Sarah Carter’s Halifax County will was written on May 21, 1799. In it, she lists Frances Tuttle as her daughter, making Frances the wife of Peter Tuttle.7 Peter and Frances Tuttle also are not a match.

Parcimus Tillery is the third Halifax County resident with the initials “PT”. Tillery first purchased land in Halifax County in 1800. This purchase and subsequent purchases were located near Fishing Creek in the western section of the county.8 He is listed in the will of his father-in-law, John Brickill. Brickill’s will was written on March 29, 1789. In it, Brickill left his son-in-law one Negro, but only after Tillery came of age. No Brickill daughters with the last name Tillery are listed as devisees, but an Eppy Tillery witnessed the document.9 Parcimus Tillery is not likely to have been the owner of the Hope press. His land is located well inland from the Roanoke River and known Seay patrons, and there is no know connection between William Seay and Tillery.

The fourth of the five potential candidates to have owned the Hope press is an individual whose initials actually match the “PRT” initials found on the press and who married a woman whose first name begins with the letter “R”. Peyton R. Tunstall was the son of Col. William Tunstall of Pittsylvania County, Virginia, and his wife, Elizabeth Barker Tunstall. William Tunstall was a member of a wealthy Virginia planter family and served as the first Clerk of Court for Pittsylvania County when it was formed from Halifax County, Virginia, in 1766. Elizabeth was the daughter of wealthy planter Thomas Barker of Bertie and Chowan Counties and his first wife, Ferebee Savage Pugh, the widow of Col. Francis Pugh of Bertie County. Upon the death of her husband in 1792, Elizabeth moved her family from Pittsylvania County to the Bertie County lands of her late father, Thomas Barker. The plantation was located near Apple Tree Ferry, south of Woodville.10

Peyton Tunstall was born in 1777, so he was a teenager when he moved with his family to Bertie County. He married in the late 1790s. This was the second marriage for his wife, Rebecca. A deed was recorded in Halifax County, North Carolina, on May 15, 1819, in which she relinquished her dower interest in a tract of land in Halifax County in favor of her son, Samuel Thomas Barnes.11 Peyton and Rebecca moved from Bertie County to Halifax County, North Carolina, by 1800. That year’s census lists his household as containing two males between 16 and 26 years of age and two females between 16 and 26 years of age. The other two household members were probably siblings. No children are listed, adding further proof of their recent marriage. They went on to have at least four children. The census also lists forty slaves in Peyton’s possession. He owned an additional 22 slaves listed in the 1800 Bertie County census, while his mother Elizabeth lists 89 slaves in Bertie County.12

By 1820, Peyton Tunstall inherited and acquired large land holdings in Bertie, Northampton, and Halifax Counties. By the mid 1820s, however, he had become heavily in debt. A number of actions against him are listed in Halifax County records. His debt grew to tens of thousands of dollars. He sold his inherited Bertie County lands as well as holdings in Northampton County in an attempt to salvage his Halifax County lands, but this was not enough. A Halifax County deed, dated May 22, 1826, notes that his remaining lands and property were to be sold to satisfy several remaining creditors. This included his home plantation, Woodstock, built by William Seay for John Drew, Jr. in 1788 and sold by Drew to Tunstall in 1803, as well as Tunstall’s other Halifax County lands. The deed also states that Peyton Tunstall’s slaves were to be sold, along with his livestock, and ‘household and kitchen furniture”.13 If he had owned the Hope press, he undoubtedly would have retained possession of it from the time it was constructed until the sale of 1826. After his reversal of fortunes, he, Rebecca, and their family appear to have moved to Franklin County, North Carolina, to be near his brother, George Tunstall. Peyton Tunstall is listed in the Franklin County census of 1830 but is not listed in the county’s census of 1840, so he most likely died between those dates.14 No record of the sale of his property in 1826 nor any estate records can be located.

Peyton Tunstall certainly had the wealth to afford a piece of furniture of the quality of the Hope press. Several of his family members married into families whose members were clients of Seay. They include his brother, William Tunstall, who married Sarah Pugh, the sister of William Alston Pugh, for whom Seay constructed the Pugh-Griffin house in 1811 and 1812. Peyton’s daughter, Lucy Tunstall, married John H. Anthony, the grandson of Whitmell Hill.15 Two factors, however, argue against his being the owner of the Hope press. Although the Hope press could contain just his initials, based on Seay’s other memorial pieces, it was probably constructed to commemorate a marriage. Peyton and Rebecca’s marriage took place in the late 1790s and was a second marriage for Rebecca. From his birth in 1777 until his father’s death in 1792, Peyton and his mother and siblings had resided in Southside Virginia and were members of a wealthy and affluent Virginia planter family. Elizabeth Barker Tunstall, and probably Peyton, were, therefore, likely to have been attuned to the latest fashion and furniture trends in Virginia, and especially to the new neoclassical style sweeping urban centers in the eastern United States, including Norfolk. While wealthy, but fairly isolated, planters of North Carolina’s Roanoke River Basin were eager to obtain furniture from William Seay and the Sharrocks, it seems doubtful these Virginians would have followed suit. It seems unlikely that they would have been willing to purchase an expensive piece of furniture that would have been out of style at the time of its purchase in the late 1790s. It seems more likely their tastes would have mimicked those of wealthy Mecklenburg County, Virginia, planters, Peyton and Jean Skipwith of Prestwould Plantation. Located just two counties east of Pittsylvania County, Prestwould was constructed in 1794. A number of family documents remain showing Skipwith purchases of fashionable furniture and accessories from Petersburg, Richmond, Norfolk, and Philadelphia.16 The wealthy Tunstalls would undoubtedly have followed suit.

Secondly, despite peripheral connections with extended family members who were patrons of William Seay, there is no evidence of any contact between Seay and Elizabeth Barker Tunstall nor Peyton R. Tunstall. Considering her wealth and the number of children she resettled in Bertie County, one would expect that if, like Whitmell Hill, her family engaged Seay for construction projects, a number of other pieces would have survived. The same holds true for Peyton and his children. So while Peyton cannot be conclusively eliminated as a candidate to have owned the press, it seems unlikely.

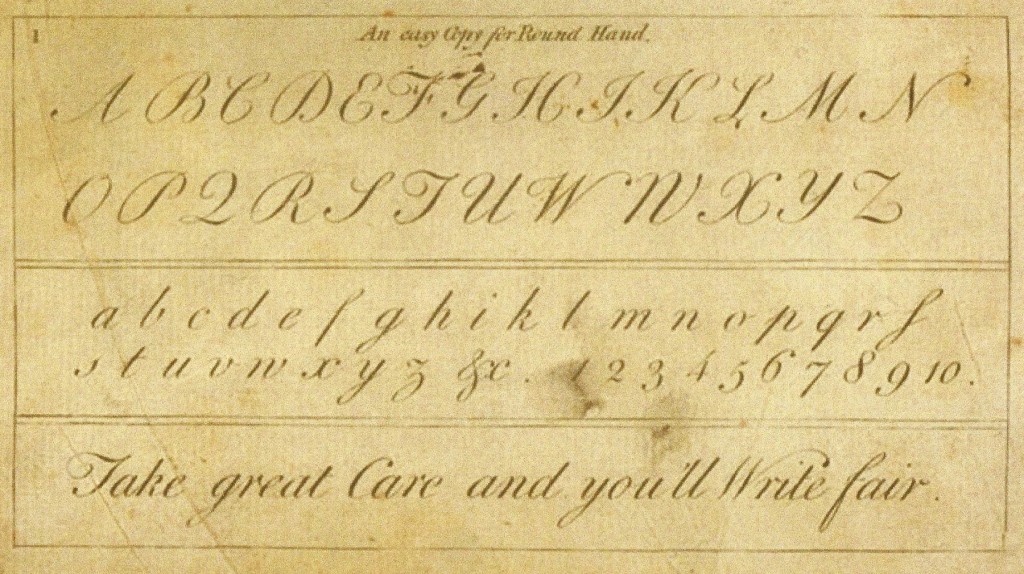

The fifth potential candidate identified during the search who might have owned the Hope press is Perry Tyler of Bertie and Hertford Counties. Perry Tyler was born after 1763 to John Tyler and his wife, Susannah Perry. Susannah Perry was the daughter of Benjamin Perry of Perquimans County. On March 3, 1755, Benjamin Perry deeded 150 acres in Bertie County to John Tyler adjacent to Peter Parker on “the Main Rd”. Joel Hollowell and Cadar Powell witnessed the deed.17 This land is located approximately five miles north of Roxobel and William Seay’s cabinet shop. When Hertford County was formed from Bertie County in 1759, the land fell just within Hertford County’s southwestern border. The 1779 tax list for Hertford County lists John Tyler owning 150 acres within its borders, with an additional 320 acres in Bertie County.18 Tyler’s Bertie holdings were located very near, if not adjoining, his Hertford County land. The Bertie property was one-half of a 640-acre land grant John Tyler received on April 20, 1758. Tyler sold the other 320 acres to the same Cadar Powell who witnessed the 1755 deed between Tyler and his father-in-law, Benjamin Perry.19

John Tyler had at least one other son, Perry’s brother, Moses Tyler. Moses was the second husband of Helen Cotton Powell, widow of Lewis Powell. Lewis Powell died in 1778 and was the son of the previously mentioned Cadar Powell.20 The Tylers were a wealthy planter family who could well afford an extravagant piece of furniture to commemorate the marriage of one of their family members. They lived only a few miles north of William Seay’s shop, so they were aware of his work and were probably familiar with the Whitmell Hill commission (Fig. 3, Map of Roxobel area). The two families were certainly acquainted with each other. Both William Seay and his brother James made purchases at the November 1800 estate sale of Perry Tyler.21

It has now been shown that the Tylers lived in close proximity to William Seay, had the wealth to afford a piece of Seay furniture such as the Hope press, and the two families were well acquainted with each other. The Tylers would have been aware of Seay’s ability to furnish a substantial commemorative piece of furniture to memorialize the wedding of a family member. The next question is whom did Perry Tyler marry and did her given name begin with the letter “R”? The answer is Rachel Hollowell. Perry and Rachel were married on February 8, 1792.22 Their union and the combination of their names created initials matching the initials on the tympanum of the Hope press. The date of their marriage is also significant. 1792 was just two years after Seay constructed the china press with secretary drawer for Whitmell Hill. Although the Hill press contains a clothes press in its lower section and the Hope press contains drawers, the two pieces of furniture are basically identical (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Figs. 2 and 5).

Rachel Hollowell was the daughter of William Hollowell, who purchased 200 acres from Thomas Williams at the juncture of Mill Branch and Connaquina Swamp in August 1754.23 This land probably adjoined the land purchased by Dr. James Seay, William Seay’s father, in 1754 (See Fig. 3). William Hollowell, one of a number of Perquimans County residents who moved to Bertie County during the third quarter of the 18th century, helped compile the 1759 Bertie County tax list. He also served as a Bertie County constable during the same period.24 Therefore, Rachel and the Hollowell family were neighbors of the Seays and certainly well acquainted with William Seay. After her father’s death, Rachel and her siblings sold family land to Reuben Norfleet.25 This land became part of Reuben Norfleet’s plantation, Woodbourne. Also, Rachel was related by marriage to the other large woodworking family in Roxobel, the Seay’s neighbors, the Sharrocks (See Fig. 3). Her brother, Arthur, married Elizabeth Sharrock on January 12, 1797. Elizabeth was the only daughter of cabinetmaker, Thomas Sharrock and his wife Bathsheba, and was therefore sister to numerous second generation Sharrock cabinetmakers.26

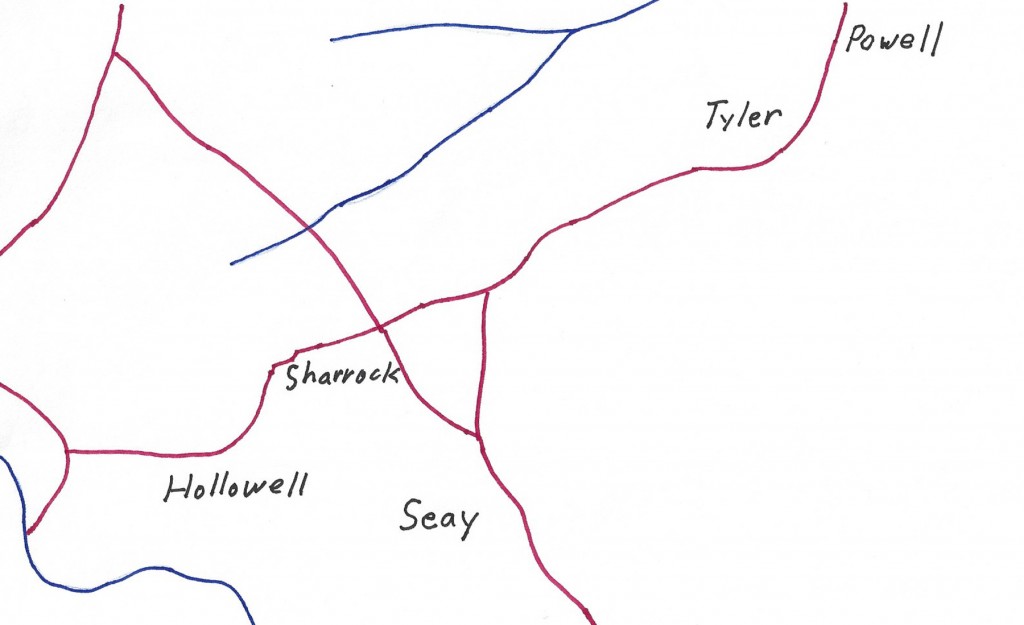

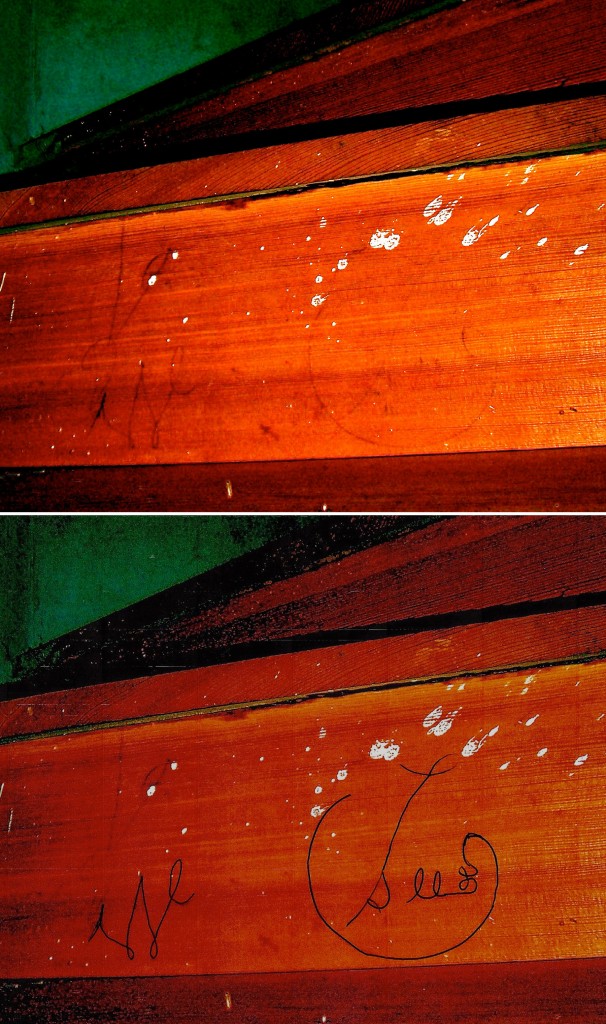

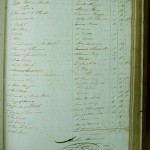

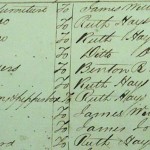

The 1792 marriage of Perry Tyler and Rachel Hollowell created a couple with initials matching those found on the Hope press. The Tylers were an affluent family who lived only a few miles north of the shop where the piece was created. The Hollowells were actually close neighbors of the cabinetmaker and his family. The next logical question in the inquiry therefore becomes whether there is any evidence that Perry and Rachel Tyler owned a piece of furniture matching the description of the Hope press. Once again, the answer is yes. Perry Tyler wrote his will on July 28, 1799. Rachel is not mentioned in the will so probably predeceased him. Perry died later in 1799, and his will was probated before the year’s end. He left a Negro girl and some personal property to Ruthey Hollowell, the daughter of Rachel’s relative, Cadar Hollowell. Perry left his nephew, Perry Cotton Tyler, son of his brother Moses, lands Perry had inherited from his father, John, in Hertford County.27 The sale of Perry Tyler’s personal property was conducted by his brother-in-law, Arthur Hollowell, one of the executors of his will, on November 29, 1800. Furniture included a chest valued at 10 shillings, a case and bottles, 18 shillings, a sugar box, 7 shillings, a table, 15 shillings, and a cupboard valued at 1 pound, 10 shillings and 6 pence. His sale also included a piece of furniture termed a “bofat” (Fig. 4, Estate of Perry Tyler) (Fig. 5, Detail of Fig. 4).28 In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the term bowfat referred to both built-in corner and flat-wall cupboards as well as freestanding corner and flat-wall cupboards used for the storage of drinking and dining wares.29 The Hope press is a freestanding flat-wall cupboard. One of its uses was for the storage of drinking and dining wares. Perry Tyler’s “bofat” sold for 8 pounds, 3 shillings, many times the value of any of his other pieces of furniture. The only more expensive pieces of furniture in his estate were two beds and furniture. The term furniture in this context described the bed’s mattress and fabrics, which were costly, thus the high value. A review of other Bertie County estate sales that took place in 1800 reveals that the Tyler’s “bofat” ranked in the upper echelon of furniture by value, other than beds and furniture, for the area and the period. The few pieces of furniture more expensive than the Tyler “bofat” usually were recorded as constructed of mahogany. A few desks sold in the 7-pound range, but most desks were much less expensive. Other bowfats sold that year included S. Turner’s example which sold for 3 pounds and a walnut example that sold for 15 shillings. Most estates did not include a bowfat. One example did sell for 10 pounds, a price commensurate with the value of the Tyler “bofat”. It was owned by wealthy planter, John Bond.30 Perry Tyler’s “bofat” therefore ranked in the upper range of this furniture form, which again matches the quality of the Hope press.

The evidence presented thus far creates a compelling case that Perry and Rachel Tyler were the original owners of the Hope press. William Seay served a client base composed of the wealthy planter families on either side of the Roanoke River. These families frequently intermarried thereby preserving and increasing their wealth. William Seay described himself as a house joiner in a 1790 deed, despite the fact that he was the owner of a large and valuable plantation, the son of a wealthy doctor and planter, and a peer of his clients. Seay was the house joiner of choice for this large, interrelated group of wealthy planters, including members of the Hill family and future Governor David Stone (Fig. 6, Seay’s name written in David Stone’s Hope Plantation) (The enhancement is based on our personal, on-site observation of the writing. The symbol above the “W” appears to be a version of a construction mark, a circle with a line drawn through it, first used by Norfolk-trained cabinetmaker, Thomas Sharrock, and later by some of his sons and probably other area craftsmen, although here beginning on its lower left with a flourish. The line drawn through the circle often returned in earlier examples.) Beginning with the Hill commission of 1790, Seay also satisfied some of the furniture needs of the same clients for whom he constructed houses. The Tylers were members of this planter elite along the Roanoke River, so they fell neatly into William Seay’s client base.

There is an additional piece of the puzzle to add to this story. As stated earlier, Moses Tyler, Perry Tyler’s brother, married Helen Cotton Powell, the widow of Lewis Powell. Lewis Powell was the son of Cadar Powell, who owned the 320-acre tract adjoining the land of John Tyler, Moses Tyler’s father. Jesse Powell, a son of Lewis and Helen Powell, lived with his mother and stepfather after his father’s death. On March 11, 1841, Jesse Powell wrote an account of his early years in Hertford and Bertie Counties. In it, he stated that his mother and her brother procured an apprenticeship for him “…with a Carpenter with whom I worked until I was 21 years old…. The man under whose direction I acquired a knowledge of the trade was so well pleased with me and another man that worked with him that he consigned to our superintendence entirely an extensive job he had undertaken. My Grandfather Cotton…gave me a little Negro boy named Nathan, who I took to work with me, and he soon became a pretty good workman.” Moses Tyler, and therefore his stepson, Jesse Powell, lived only four miles north of William Seay’s cabinet shop. In WH Cabinetmaker…, we discussed the likelihood that Seay maintained more than one construction crew at any given time, with men such as Thomas Sharrock or Lewis Murdaugh, Seay’s son-in-law, serving as foremen. This is a highly unusual practice and no other house joiners have been discovered in the Roanoke River Basin who conducted business on the scale to employ multiple crews. Jesse continued, “I had a good deal of work and have often been at my work bench waiting for it to become light enough for me to commence work.”31 This statement implies the presence of a purpose-built shop in which to house a workbench. It is unusual for a carpenter or house joiner to have the need for a shop. It was certainly more convenient to create and assemble interior trim, doors, and wainscot on the house site than to transport the finished material to the house site from another location. William Seay, however, had a shop at least by 1790. Seay added a shed to his shop shortly after it was constructed and probably after the Hill commission. The shed’s roof rafters were attached to the shop rafters, creating over ten and one-half feet in ceiling height in the shed for more conveniently assembling and finishing large case pieces. During the shop’s on-going restoration, in addition to evidence of bench locations as well as the location of the placement of the tension rod of a bow lathe, rows of small wrought nails were found set horizontally every three to three and one-half feet the full height of the rear plank wall of the shop, so therefore on the interior wall of the shed. Based on their exposure above the wood of the wall, they most certainly supported strips of wood set horizontally every three to three and one-half feet. The only logical purpose for these strips of wood would be to support a cloth or canvass on the wall of the shed to prevent saw dust and debris from penetrating through the small spaces between the logs of the rear plank wall of the shop into the shed where furniture was being finished. This type of feature would only be necessary in a cabinet shop.

Considering Powell’s place of residence, the volume of his master’s workload, and his description of his work place, William Seay is the obvious candidate to have been his master. Seay had other connections with the Powell family. He constructed a house for Jesse Powell’s brother, Cadar Powell, and a Seay Masonic corner cupboard descended in the family of another brother, Willis Powell. The corner cupboard was constructed between 1792 and 1796, so potentially during Jesse Powell’s apprenticeship. (See WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 95-99 and 219-221). Jesse Powell was born on December 5, 1772, so he would have completed his apprenticeship in 1793. This in all likelihood places the stepson of Perry Tyler’s brother, Moses Tyler, in the Seay cabinet shop in 1792 when the Tyler press was being constructed. Jesse Powell would also have been acquainted with the Whitmell Hill commission of 1790, which included the “WH” press matching the Tyler press. Jesse Powell maintained a presence in Roxobel’s woodworking community even after he moved to Halifax County in 1807 after completing his apprenticeship. He and his family are listed in the 1810 Halifax County Census along with eleven slaves.32 His name also appears in the Bertie County Census of 1810.33 Seven slaves are listed under his name, but no whites are included in this listing. His name is listed directly after Bathsheba Sharrock and two names before Lemuel Murdaugh, Seay’s son-in-law who was living on the Seay plantation. This places Powell’s seven slaves, who had probably been trained by Powell as woodworkers, directly between the two major woodworking families in Roxobel. If these slaves were merely farm hands, he could have leased them out in Halifax County. Powell continued to train a number of his slaves as woodworkers throughout his life based on the training he received from Seay as a young man. In his will dated March 14, 1859, four of his slaves are listed as carpenters, and he included a devise that “My carpenters are to build a house for said John T. Watson,” who was Powell’s grandson.34 Jesse Powell’s house still stands in Halifax County near Scotland Neck. Its front section was constructed after he purchased the property in 1807, and it was originally a tripartite structure, a favorite Seay house design. Its exterior cornice is original to this period and is composed of two rows of dentils alternating with the sawtooth design also favored by Seay. A similar element employing dentils alternating with demilunes rather than the sawtooth design is found on the exterior cornice of the Sally-Billy house, constructed by Seay around 1810 (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Fig. 354). The transom over the hall entrance of Jesse Powell’s house displays demilune-shaped lights similar to those found at The Hermitage, built by Seay in 1793 for Whitmell Hill’s son, Thomas Blount Hill, and at Woodstock, built by Seay in 1788 for John Drew, Jr. (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Figs. 57 and 366). Therefore both houses, The Hermitage and Woodstock, based on their date bricks, were constructed during Jesse Powell’s apprenticeship. It should be noted that in his 1841 memoir, Powell described the second man with whom he shared the superintendence of the “extensive job” as an individual who worked “with” the carpenter rather than “for” the carpenter. Furthermore, Thomas Sharrock has been shown to have been on site during the construction of Woodstock in 1788 when he witnessed two deeds for the owner, John Drew, Jr.35 Jesse Powell is undoubtedly but one of a number of former Seay apprentices and journeymen whose later Seay-influenced work is yet to be discovered.

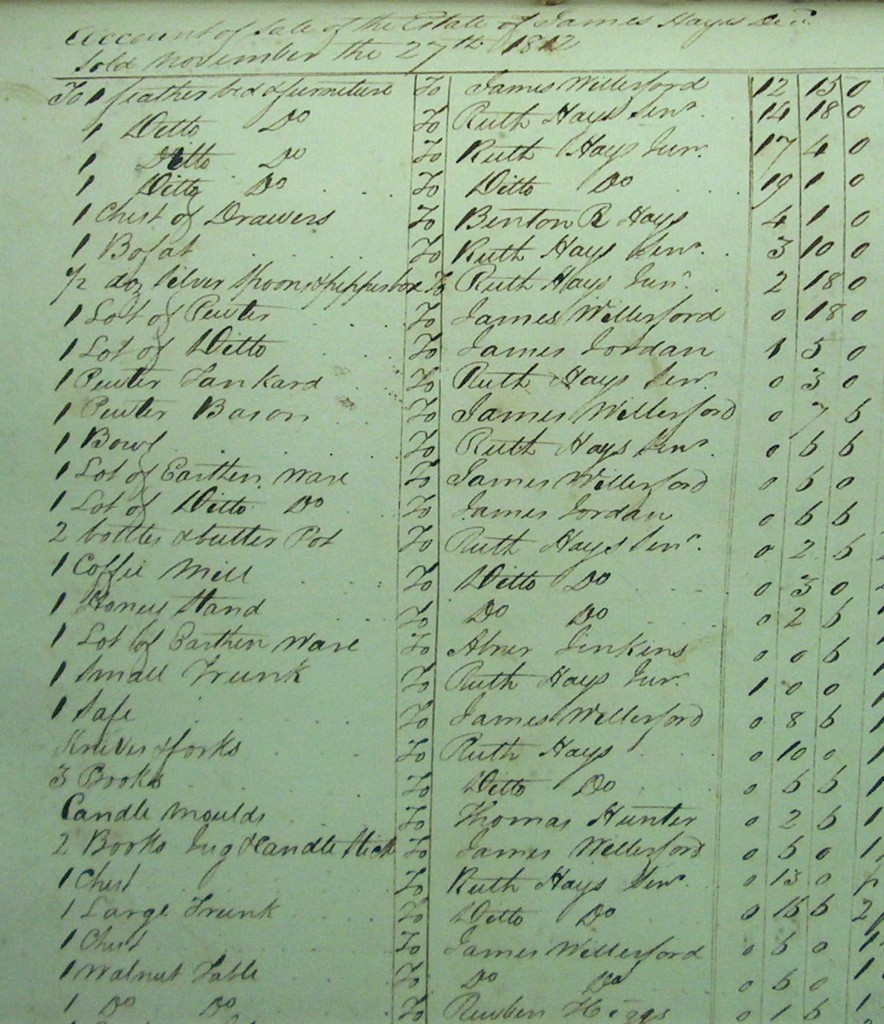

With compelling evidence having been presented to show that the Hope press was constructed to commemorate the marriage of Perry Tyler and Rachel Hollowell, it is time to meet the next owners of the press. James Hayes purchased the “bofat” at Perry Tyler’s estate sale for 8 pounds and 3 shillings (See Figs. 4 and 5). James Hayes and his wife Ruth lived on the south side of Cashie Swamp just north of the property of John E. King. King was the son of Michael King, probably placing him on King-family holdings west of Hope Plantation. On Saturday, May 26, 1810, one Anthony Wiggins “with a certain hoe then and there in his right hand of his malice aforethought did give the aforesaid James Hayes several mortal wounds upon and about the head which broke his skull in several places….” Wiggins’ wife, Mary, and a slave, Tom, were found to have aided Wiggins in hiding Hayes’ body. The sale of James Hayes’ personal property took place on November 27, 1812. The “bofat” was included in the sale (Fig. 7, Estate of James Hayes) (Fig. 8, Detail of Fig. 7). Ruth Hayes, James’ widow, purchased the ”bofat” for 3 pounds and 10 shillings.36 This was still a substantial sum. Except for four feather beds with furniture, this “bofat” was the second most expensive piece of furniture in the sale. The reduced price is probable reflective of changing styles and the growing influence of neoclassical Norfolk furniture in northeastern North Carolina.

This persuasive evidence identifies the first owners of the Hope press as Perry and Rachel Tyler, and the second owners as James and Ruth Hayes. The identity of the press’ owners through 1812 is additional proof that William Seay was the builder of the piece of furniture. There is no other logical explanation for his incised signature being present on the upper edge of an interior drawer side of a piece of furniture owned by the Tylers and the Hayes from 1792 through 1812. Also, it would be very difficult, even for a skilled craftsman like Seay, to have leaned into a finished drawer to incise a signature of the quality that can be compared definitively to his written signature on apprentice agreements. It is much more likely that Seay incised his name after the drawer components had been fabricated but before they had been assembled. Its location at the top edge of the interior drawer side, along with its being incised rather than being written with a pencil or with ink, was an attempt to prevent its discovery. The signature would have been more visible if it had been placed in the middle or lower edge of the drawer side. We may never known the identity of the person whose name Seay incised behind his name or why Elizabeth, the person’s first name, caught his fancy. Other period cabinetmakers, including John Shearer of northwestern Virginia and Maryland, wrote words and dates on the show surface of the furniture they made. Shearer also wrote hidden messages on the furniture he created, some of which were derogatory comments about the very patrons who were purchasing his work.37 Experts, scholars, and interested parties had thoroughly examined the Hope press and other Seay pieces over the years for evidence of the maker of the “WH” series. William Seay successfully kept his message safely from the public eye for over 200 years.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

Figures 4, 5, 7, and 8 are published courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Endnotes:

- F. Carey Howlett and Kathy Z. Gillis, “Scientific Imaging Techniques and New Insights on the WH Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Continues”, American Furniture, 2013, pp. 78-79.

- Ibid., p. 75.

- George Fisher, The Instructor, or Young Man’s Best Companion Containing Spelling, Reading, Writing and Arithmetic, Glasgow, Scotland, 1786.

- Halifax County Will Book 3, p. 115.

- Halifax County Will Book 3, p. 447.

- Halifax County Will Book 3, p. 307.

- Halifax County Will Book 3, p. 331.

- Halifax County Deed Book 18, p. 674, Book 19, p. 142, Book 22, p. 435, and Book 28, p. 247.

- Halifax County Will Book, p. 167.

- Sally’s Family Place, Francis Pugh, www.sallysfamilyplace.com.

- Halifax County Deed Book 25, p. 40.

- Halifax County Census of 1800 and Bertie County Census of 1800.

- Halifax County Deed Book 27, p. 87.

- Franklin County Censuses of 1830 and 1840.

- Sally’s, Francis Pugh and Franklin County Deed Book 26, p. 607.

- Ronald L. Hurst, “Prestwould Furnishings”, The Magazine Antiques, January, 1995, pp. 162-167.

- Sally’s, Benjamin Perry.

- Hertford County Tax List, 1779.

- Bertie County Deed Book I, p. 126.

- Sally’s, Cadar Powell.

- State Archives, Bertie County, Record of Estates, Vol. 10, p. 102.

- Elizabeth Smith Dunstan, The Bertie County Index, 1720-1875, Self-published, 1966, Marriage Bonds.

- Bertie County Deed Book H, p. 112.

- Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved, Legacy Ink Publications, 2009, p. 227.

- Bertie County Deed Book P, p. 169.

- Newbern and Melchor, p. 227.

- Bertie County Will Book E, p. 91.

- State Archives, Bertie County, Record of Estates, Vol. 10, p. 102.

- Betty Crowe Leviner, “Rosewell Revisited”, The Journal Of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. XIX, Number 2, Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1993, p. 56.

- State Archives, Bertie County Estates, Book L, pp. 194, 207, and 253.

- Sally’s, Helen Cotton.

- Halifax County Census of 1810.

- Bertie County Census of 1810.

- Halifax County Will Book 5, p. 79.

- Henry V. Taves, Allison H. Black, and David R. Black, The Historical Architecture of Halifax County North Carolina, The Halifax County Historical Association, Halifax, NC, 2010, pp. 284-285 and Newbern and Melchor, pp. 238-240.

- State Archives, Bertie County, Record of Estates, Vol. 15, p. 409.

- Elizabeth A. Davison, The Furniture of John Shearer 1790-1820, AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD, 2011, pp. 100, 102, 126, 130-131, 149, and 178.