By Michael L. Marshall

The Hoomes Family

The history of Bowling Green, a small Tidewater town in Caroline County, Virginia, and the early colonial home there known today as Old Mansion, are both inextricably linked with the Hoomes family.1 Unfortunately, it is not possible to construct a history of the family’s early years because many of Caroline’s records were destroyed during the Civil War. According to Thomas Campbell, the earliest member of the Hoomes line in that vicinity was Thomas, who received a grant of 3,000 acres in 1667 and an additional 523 acres in 1674.2 There is no record of his death, nor is there evidence of a wife or children.

Only one Hoomes appears on the 1704 Virginia quit rent rolls: George Hoomes of King and Queen County, who is credited with 725 acres. Since Caroline County was formed in 1728 from parts of Essex, King and Queen and King William Counties, he may have been living in that part of King and Queen that later became Caroline. He may also be the man whose estate was settled in Caroline in 1733 by Christopher and George Hoomes. According to Malcolm Hart Harris’ Old New Kent County, he had several children: George Hoomes [Jr.], Christopher, Joseph, Benjamin and Priscilla.3 Campbell says this George Hoomes was a medical doctor and practiced “at the Bowling Green.”4

During the period 1732-1745, George, Benjamin and Joseph Hoomes all served as jurors in Caroline.5 George, described in the records as a “great planter,” was appointed a magistrate of Caroline County in 1735 by Virginia Governor, Sir William Gooch.6 Joseph Hoomes, also called a “great planter,” was appointed a Caroline magistrate in 1751 by Governor Robert Dinwiddie.7 The following year, George Hoomes was appointed a justice of Caroline Court at a meeting of the Virginia Council held on April 30, 1752.8 A commission of the peace for Caroline appointed by the Council on June 10, 1752 included George and Joseph Hoomes.9 In addition, there is a merchant’s account book for King and Queen County, kept during the years 1750-1751, that mentions “Capt. George Hoomes,” “Capt. Joseph Hoomes,” John Hoomes, “carpenter on the Dundee” and Stephen Ferneau Hoomes.10 There is evidence suggesting this store was located in the middle to upper end of the county. The Capt. Joseph Hoomes may be the man whose estate was settled in 1754 by Susannah (Waller) Hoomes and Edmound Pendleton.11

George Hoomes’ estate was settled in 1753 by Edmound Pendleton, John Baylor and Stephen Ferneau Hoomes. He is probably the George Hoomes Jr., mentioned earlier, but this is not certain. John Baylor handled the portion of the estate in Culpeper and Orange Counties, Stephen Ferneau Hoomes, the portion in Caroline, and Pendleton attended to certain other legal aspects of the settlement.12 According to family Bible records, this George Hoomes had a wife named Frances, and they were the parents of a son, John Hoomes, born October 20, 1749.13 After reaching adulthood, he married Judith Churchill Allen on October 2, 1768.14 Born July 1, 1749, Judith was the daughter of Richard Allen and his wife, Elizabeth Terrell, daughter of Richmond Terrell of Blisland Parish, New Kent County, Virginia.15

In later years, John Hoomes, by then widely known as Col. John Hoomes, became an important social and political leader in Caroline County and a man of great wealth. One of his first efforts involved the construction of a tavern, which was located on his estate at the intersection of the stage road and a “rolling” road utilized to transport hogsheads of tobacco to Port Royal, a small village on the Rappahannock River. This was probably the “new building at the Bowling Green” mentioned in his 1774 application for a license to keep a tavern.16 The village that grew up around the tavern became known as New Hope, as did the tavern itself. However, when the village later became the county seat of Caroline, the name of the town was changed to Bowling Green, after Bowling Green farm, the original name of the Hoomes plantation. Thereafter, the Hoomes plantation came to be called Old Mansion, a name it still bears today.

In 1776, Col. Hoomes was appointed a magistrate of Caroline County by Virginia Governor, Patrick Henry, a position he held throughout the Revolution.17 He was also a member of the first vestry of the newly established St. Asaph’s Parish in Caroline, along with Edmound Pendleton, Edmound Pendleton, Jr., Anthony Thornton Jr., Mungo Roy, David Jameson, Philip Johnston, Charles Todd, Charles Woolfolk and Thomas Buckner.18 In 1781, Hoomes established a stagecoach company with lines that ran from Richmond to Hampton, Virginia, by way of Petersburg, and in October 1784 the state granted him a three-year monopoly for this enterprise.19 The legislature also awarded him the exclusive right to operate a stage line between Alexandria and Fredericksburg and from Fredericksburg to Richmond and Hampton. Hoomes also served as postmaster at Bowling Green from June 1790 until 1796, as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates from 1791 to 1795 and as a member of the Virginia state senate from 1796 to 1803.20

Col. Hoomes died on his plantation on December 16, 1805. An obituary in the Enquirer of Richmond dated December 27, 1805, had this to say about him: “With pain it falls to our lot to record the death of Col. JOHN HOOMES, on the 16th inst. after a painful and lingering illness, which he bore with the greatest fortitude and Christian resignation. He has left a widow and an amiable family of children to lament the loss of a tender husband and affectionate parent . . .” At his death, his large estate was disposed of by a will dated July 22, 1805, and proved January 14, 1806, by his two executors, John George Woolfolk and John Hoomes, his son.21 A copy of the will, which can be found in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, names as devisees his wife, Judith, sons John, William, Richard and Armistead, daughter, Sophia, and grandson, John Waller Hoomes, son of his deceased son, George Washington Hoomes.22 His widow was left a life estate in “the tract of land whereon I now live, comprised of the Bowling Green, and sundry purchases so as to form one entire tract of about 4,000 acres,” as well slaves and other personalty. The will also gave each of his surviving children and grandson land and slaves, in fee simple, but directed that if any of them should die without issue living at their death, their share of the estate should be divided equally among the survivors, or their representatives, according to the principles of the law of descents. All of the devisees survived the testator and took possession of the estates devised to them.

Col. Hoomes’ son, William, died in February of 1819.23 Thereafter, the remaining heirs claimed that his share of his father’s estate should be divided among them and the court so ordered on September 12, 1819.24 Judith Hoomes died in August of 1822, and her sons, John and Richard, died two years later: Richard on January 3, 1824, and John on March 14, 1824.25 A year before his death, Richard established a trust for his wife Hannah (Battaile) and their children, John, Richard, Judith A., George, Hay and Mary W. Hoomes. In the trust papers he stated that he had sold a large tract on Polecat Creek and another called Milford, both in Caroline County.26 Richard’s brother, John, died at Bowling Green, leaving no heirs, but an estate of some 3,442 acres.27 In August of the same year, Sophia (Hoomes) Allen, Armistead Hoomes, John Waller Hoomes and the heirs of Richard Hoomes had a survey and plat drawn for 2,694 acres covering “Bowling Green,” in order to divide the land.28 Armistead Hoomes, the last son of Col. John, died on February 6, 1827.29

Old Mansion, The House

For many years it was widely contended that the original Hoomes family home, called Old Mansion today, had been built in the seventeenth century. Marshall Wingfield’s history of Caroline states that “Just when it was erected cannot be definitely stated but it is quite certain that it was not later than 1675.”30 In 1969, when the house was nominated for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places by its then-owner, Miss Anne Maury White, the description of the house claimed that it was built “circa 1670 on a 17,000 acre land grant.”31 Numerous other commentators have made similar claims regarding its supposed seventeenth century origins. It was not until the house and the surrounding property were sold in 2003 to Steve Nicklin that the real age of the house was determined by tree-ring analysis or dendrochronology. Nicklin hired the Oxford Tree-Ring Laboratory to examine the timbers in the house to determine when they were cut. According to their analyses, the front-range felling dates were Winter 1738/9, Spring 1739, Summer 1740, Winter 1739/40, Winter 1740/41, Spring 1741, and Summer 1743.32 So the original house was built during the interval from 1739-1743. A rear section that had been added to the house dated to a second phase of construction, with felling dates of Spring 1790 and Spring 1791.

The original (front) block (Fig. 1, Front View of Old Mansion) is a one and one-half story brick structure with dormers and a jerkin-head roof with exterior chimneys. The brick in the water table is English bond and above, Flemish bond with glazed headers. The nine-over-nine pane windows have flat, rubbed, brick arches, whereas the basement windows have segmental arches. The narrow dormers feature hipped roofs. The frame addition added to the rear of the original house in the early 1790s is covered by a gambrel roof with shed dormers. (Fig. 2, Side View of Old Mansion showing 1790s extension) As is the case with the original part of the house, the addition too has a modillioned cornice.

Old Mansion was likely one of the finest houses in Caroline when President George Washington visited the county on April 10, 1791. Washington recorded the event in his diary: “Sunday 10th. Left Fredericksburgh about 6 Oclock. Myself, Majr. Jackson and one Servant breakfasted at General Spotswoods. The rest of my Servants continued on to Todds Ordinary where they also breakfasted. Dined at the Bowling Green and lodged at Kenner’s Tavern 14 Miles farther–in all 35 [miles].”33

While the name of the man who built the original section of Old Mansion cannot be definitely stated, it seems that a likely candidate may be the George Hoomes Jr., whose estate was settled in Caroline in 1753; his son, Col. John Hoomes, most likely inherited the property from him.

William Grymes Maury

Because of losses to Caroline County’s early land records, it is not possible to develop a complete chain of title to Old Mansion following its ownership by Col. John Hoomes. However, it is known that it was sold in 1842 to William Grymes Maury.34

According to a history of the Maury family published by the Fontaine-Maury Society, from which the following information regarding these families is largely taken, the Maury and Fontaines were Huguenots that fled France following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.35 The families were united on October 20, 1716, when Mary Anne Fontaine and Matthew Maury were married in Dublin, Ireland. Matthew, who had come to Dublin from France around 1714, was the son of Abram Maury and Marie Feauguereau, his wife, to whom he was born on September 18, 1686 in Castel Mauron, Gascony, France. In February 1717/18, Matthew sailed for Virginia with a shipment of trade goods and arrived there the following month, joining his brothers-in-law, John and James Fontaine. After settling on a tract of land near present-day West Point, Virginia, Mathew returned to Dublin to retrieve his wife and infant son, James. Together, they sailed for America in September 1719, along with thirteen servants, and settled on his property in what is today King William County, Virginia. Following Matthew’s death in 1752, his widow moved to Charles City County, Virginia, to live with her brother, the Rev. Peter Fontaine.

Matthew’s son, James Maury, who was born in Dublin on April 8, 1718, married on November 11, 1743, to Mary Walker, daughter of Ann Hill and Dr. James Walker of Louisa County. Their children included a son, Walker Maury, who was born July 21, 1752, in Albemarle County. He married in Williamsburg, Virginia, on March 7, 1777, to Mary Stith Grymes, daughter of Ludwell Grymes and his wife, Mary Dawson. Their children were Mary Stith Maury, born June 7, 1778; James Walker Maury, born March 18, 1779; Leonard Hill Maury, born December 4, 1780; Ann Tunstall Maury, born September 5, 1782; William Grymes Maury, born March 29, 1784; Penelope Johnstone Maury, born June 23, 1785; Matthew Fontaine Maury, born September 15, 1686; and Catherine Ann Maury, born May 20, 1788.36

However, before returning to a discussion of William Grymes Maury, it is necessary to mention his sister, Ann Tunstall Maury, who became the second wife of Maj. Isaac Hite of Belle Grove plantation located in the northern Shenandoah Valley in Frederick County, near Middletown, Virginia, and about the Hite family itself (Fig. 3, Photograph of Ann T. Hite, Courtesy: Fred Barr Collection, Stewart Bell, Jr. Archives Room, Handley Regional Library, Winchester, VA) (Fig. 4, Belle Grove).

Belle Grove was built between 1794 and 1797 by Hite and his first wife, Nelly Conway Madison, sister of President James Madison. Hite married Nelly on January 2, 1783. Hite was the grandson of Shenandoah Valley pioneer, Hans Jost Hite, who came from Alsace to Kingston, New York, in 1710 as part of the great Palatine migration. From Kingston, Hite and his family moved first to Germantown, Pennsylvania and then in 1732, on to the Shenandoah.37 Hite and his partner, Robert McKay, had two grants there, one for 100,000 acres and another for 40,000, on condition that one hundred families would be settled on the land within two years. However, these grants were challenged by Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax, who claimed the land was part of the Northern Neck Proprietary granted to his family by King Charles II of England and that the Council and Governor had no right to make these grants.38 The case dragged through the courts for many years before being settled in 1786 at which time title was finally given to Jost Hite’s heirs. Maj. Isaac Hite received 483 acres of land in Frederick County, Virginia, in 1782 or early 1783, which were granted to him by his father, also named Isaac Hite, and it was on this land that he constructed Belle Grove based on a design suggested by Thomas Jefferson.39

Isaac Hite attended William and Mary College and was among the first one hundred Phi Beta Kappa members there; the society had been founded at William and Mary on December 5, 1776. He left the college in 1778 to join the Virginia 8th Regiment under the command of Col. Peter Muhlenberg, but later transferred to the Continental Army as an aide-de-camp to Muhlenberg at the time Muhlenberg was promoted to General. After the war, Hite continued his public service as a Major in the Frederick County Militia, as a member of the Virginia delegation at the Constitutional Convention and as a Justice in Frederick County.40

Following the death of his first wife Nelly on December 24, 1802, Maj. Hite married on December 1, 1803 to Ann Tunstall Maury, sister of the previously mentioned William Grymes Maury.41 Their children included: Ann Maury Hite, born June 17, 1805, who married Philip Williams; Isaac Fontaine Hite, born May 7, 1807, who married Maria Louise Davison; Mary Eltinge Hite, born October 26, 1808, who married John Smith Bull Davison; Rebecca Grymes Hite, born May 12, 1810, who married Rev. John Loder; Walker Maury Hite, born may 12, 1811, who married Mary Eleanor Williams; Sarah Clark Macon Hite, born November 7, 1812, who married Mark Bird; Penelope Elizabeth Lee Hite, who married Raleigh Brook Green; Hugh Holmes Hite, born August 10, 1816, who married Ann Randolph Meade; Cornelius Baldwin Hite, born February 25, 1818, who married Elizabeth Augusta Smith, and Matilda Madison Hite, born June 9, 1819, who married Dr. Alexander Davison.42

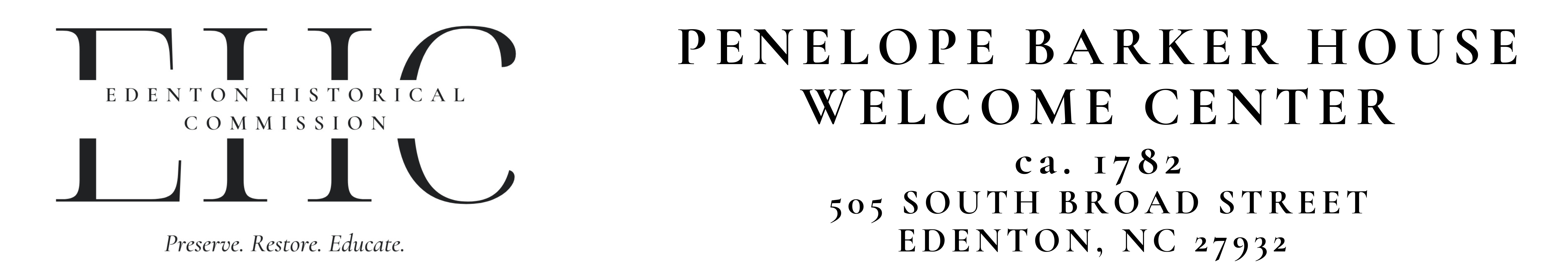

Major Hite died at Belle Grove on November 24, 1836, and his second wife, Ann Tunstall (Maury) Hite, died there on January 6, 1851.43 Today, Belle Grove is owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which operates it as the Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park. The house was used by Union General Philip Sheridan during the Battle of Cedar Creek, which was fought on October 19, 1864.

Although it was not until 1842 that William Grymes Maury acquired Old Mansion, he had been in Caroline since the early 1800s and had connections to the Woolfolk family of Caroline that resided at Shepherd’s Hill plantation. This was the family of John George Woolfolk, who, like Col. John Hoomes, was also involved in the stagecoach business. Woolfolk family companies included the Potomac Steamboat & Stage Company, Allen & Company, Jourdan Woolfolk & Company and Woolfolk & Hoomes.44

It was John George’s daughter, Ann Hoomes Woolfolk, who married William Grymes Maury, the marriage taking place on July 14, 1808.45 Together, they had nine children, including a daughter, Finella Strachan Maury. Finella, born at Burnettes in Caroline County, Virginia, on April 11, 1815, married at Antioch Church in Caroline on December 12, 1839, to James Thompson White, who was born at Audley in Spotsylvania County on December 31, 1803.46

William Grymes Maury continued to farm Old Mansion until his death in 1860.47 An obituary giving notice of his passing appeared in the February 17, 1860, issue of the Richmond Whig: “At the ‘Old Mansion,’ Caroline County, Va., on the 9th instant after a well-spent life, and in the 76th year of his age, WILLIAM G. MAURY, beloved and lamented by all who knew him.” His wife, Ann Hoomes (Woolfolk) Maury, preceded him in death, passing away on January 10, 1856. A notice of her death appeared in the January 16, 1856, Richmond Dispatch: “ DIED—on the 10th inst. at Bowling Green Mansion, Va., after a protracted illness, Mrs. Ann H., wife of Mr. William G. Maury.”

In 1862, the house and land passed to Maury’s son-in-law, James Thompson White and his wife, Finella, and they continued to farm the land, planting both cotton and tobacco. Finella died May 1, 1886, and White on November 17, 1887; both were buried at Shepherd’s Hill.48 Old Mansion then descended to their son, John Lewis White, who married Elfie May Cary, and from them to their children: John Cary White, born October 21, 1882, and his sister, Anne Maury White, born March 8, 1887. John Cary died on January 25, 1949, at which time the property came into the sole possession of his spinster sister, Miss Anne Maury White.49 Miss White, who died on April 5, 1970, left the house and land to the children of her first cousin, in trust, viz., John Howe Cecil, Jr., Patricia Cecil Haas, John B. Cary, Jr. and Jane Abeit Cecil.50 In 2003, these heirs conveyed the property to Steve Nicklin and sold, or otherwise disposed of the house’s contents.

‘Tis friendship stamps the value

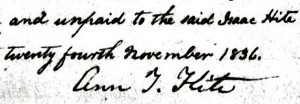

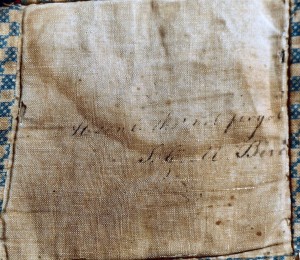

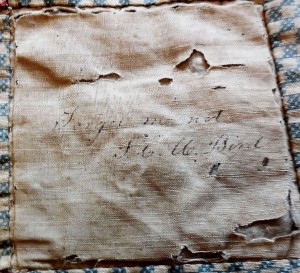

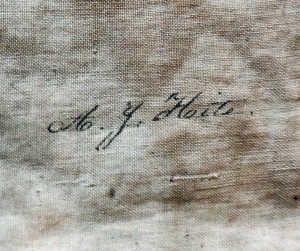

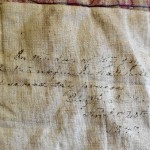

Among the items dispersed following the 2003 sale of Old Mansion was a friendship quilt. (Fig. 5, Front of Quilt showing signature blocks) (Fig. 6, Back of quilt) Two of the signature blocks were signed and dated by Ann T. Hite. This is Ann Tunstall (Maury) Hite, wife of Maj. Isaac Hite of Belle Grove and sister to William Grymes Maury, who acquired Old Mansion in 1842. One of the blocks (Fig. 7, Ann T. Hite quilt block) is inscribed: ‘Tis friendship/stamps the value/Ann T. Hite/Belle Grove/May 3rd, 1845,” and the other (Fig. 8, Ann T. Hite quilt block), ‘Tis friendship stamps/the value/Ann T. Hite/Decbr 3rd, 1847.” From this, it might be surmised that work on the quilt was commenced in 1845 and that it was still in the hands of the mistress of Belle Grove in 1847. Whether the actual dates have any special meaning is unknown. Given that this quilt ended up at Old Mansion, it seems it was intended as a gift to Maury from his sister and other friends and relatives. Ann’s signatures in the two quilt blocks compare favorably with one she inscribed on an affidavit sworn before a Justice in Frederick County, Virginia, on September 8, 1843, that is contained in her husband’s Revolutionary War pension file (Fig. 9, Handwritten signature of Ann T. Hite).51

Research indicates that usage of the phrase “stamps the value” appears in numerous contexts during the nineteenth century, including some connected with friendship. For instance, it is used in the Latin expression, “Auctor pretiosa facit,” which translates to “The author stamps the value.” The expression “confidence stamps the value of friendship,” can be found in a book of maxims and reflections printed in 1830.52 In addition, a magazine devoted to proceedings of the Odd Fellows in Manchester, England, includes an example published in 1829 in connection with a gift of friendship: “Worthy friends, you have presented me with this handsome and valuable token of your esteem . . . and whilst memory keeps possession your friendship will not be forgotten; yet permit me to state to you it is not the value of this gift that I so highly prize, no is it your esteem, it is your friendship which I prize, and it is that alone which stamps the value on the gift.”53 It is not possible to know how Ann T. Hite conceived the idea of the verse she used in both her blocks, but it is clear that the expression was still in common use at the time she began work on the quilt.

Before proceeding to a discussion of other verses and signatures inscribed on the Old Mansion quilt, it might be useful to say a few general words about signature, or autograph quilts, of which there are two distinct types: those that exhibit blocks following a single pattern, and those comprised of differing patterns. The former are usually called friendship quilts and the latter, sampler album quilts.

Quilt historian and author Barbara Brackman explains that, during the decades between 1840 and the end of the Civil War, “quilts took on new meaning as women began making them to raise funds for various purposes and to symbolize political issues and friendship.”54 This evolution was facilitated by technological progress that enabled the production of an increasing variety of new fabrics, including advances in roller printing and dye chemistry. These new quilt forms began to appear around 1840, and represented an extension to textiles of the concept of bound paper albums that had been popular since the 1820s. As Brackman notes, “Friends might each sign a block for a quilt made up of squares of an identical pattern worked in different fabrics; or they might each contribute a block in a different design.”55 The blocks in these quilts often featured elaborate ink signatures accompanied by verses taken from poems, religious texts and other sources. As the name suggests, they were made as gifts to a friend or relative, who, in some cases, might have lived at a distance, thus providing a way for them to remain connected. In some examples, the names and verses inscribed in the signature blocks were not the only significant part of the quilt, as some blocks may have incorporated fabric from a childhood dress, or a block design chosen to remind the quilt’s recipient of its makers. 56

The Old Mansion quilt is approximately 67” in length x 53” in height. Regrettably, both the front and the back of the Old Mansion quilt have suffered serious deterioration, especially the back side (see Fig. 6). The quilt had been stored for many years in an old wooden blanket chest at Old Mansion, and it is likely that the volatile acids emitted by the wood played a part in weakening the quilt fibers. Acid can also lead to yellowing, and this too can be observed in many areas of the quilt. It is also probable that some of the dyes used in the roller printing process have contributed to the quilt’s deterioration, not to mention the extremes in temperature and humidity it must have experienced over its nearly one hundred and seventy year history.

The Old Mansion quilt has twenty individual blocks. It might be presumed that each one was signed by its maker but, if so, some of the inscriptions have faded completely away, at least to the visible eye. Others remain legible, or partly legible, but they too have faded as the ink diffused into the fabric on which they were written. This makes it difficult or, in some cases, impossible to read either the inscriptions remaining, or the signature of the maker, or both. Those that can be read, at least in part, are discussed next.

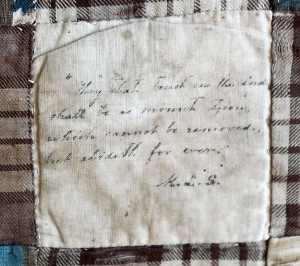

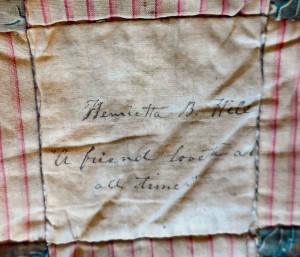

Two of the blocks (Fig. 10, M. L. S. signature block) (Fig. 11, Henrietta B. Hill signature block) contain verses taken directly from the King James Version of the Holy Bible. The block shown in Fig. 10 was written by someone whose initials appear to be “M. L. S,” and incorporates the following verse: “They that trust in the Lord/shall be as mount Zion/which cannot be removed/but abideth for ever.” This comes from the Book of Psalms, specifically Psalm 125, Verse 1. The block shown in Fig. 11 is signed by Henrietta B. Hill and is inscribed “Henrietta B. Hill/a friend loveth/at all times.” This expression comes from the Book of Proverbs, Chapter 17, Verse 17, which reads in its entirety: “A friend loveth at all times, and a brother is born for adversity.” The expression used by Henrietta is likely meant to convey the message that she is a true friend of the family, one who loves in times of adversity as well as in times of prosperity.

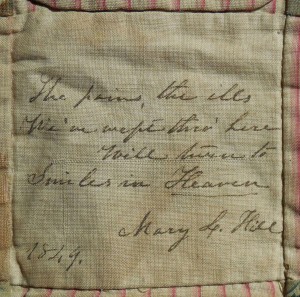

Interestingly, there is another block constructed of the same fabrics as those used by Henrietta, and it is signed by Mary L. Hill. (Fig. 12, Mary L. Hill signature block) Henrietta B. and Mary L. Hill were sisters and appear together in the 1850 federal census in the household of Louisana Redd of Caroline County, Virginia. Henrietta’s age is given as 34 years, Mary’s as 31 years and Louisana’s age as 38 years. Besides these three women, the household also contained a child, Ann R. Redd (age 7) and an elderly male, Richard Hill (age 73). The specific connection between the Hill and Maury families is unknown, but it may be through the marriage of William Grymes Maury’s daughter, Mary E., to a W. Hill.57 Who this “W. Hill” is has not been discovered. Louisana was also a sister to Henrietta and Mary. This information comes from an obituary that appeared in the January 4, 1867 Richmond Whig: “HILL—At the residence of her sister, Mrs. L. Redd, in Caroline county, Va., at 1 o’clock, A. M., December 31, 1866, Miss MARY L. HILL, after a painful and lingering illness.” But getting back to the quilt block itself, it can be seen that the inscription reads, “The pains, the ills/we’ve wept thru here/will turn to/Smiles in Heaven/Mary L. Hill/1849.” This verse comes from a poem by the Irish poet, Thomas Moore, who was born in Dublin on May 28, 1780; the poem is called “When Twilight Dews.”58 The poem must have been a popular one in the nineteenth century because it was set to music and can be found in numerous songbooks of that era. This could account for its availability in the Hill family household of Caroline County in 1849, when Mary L. Hill used it in her quilt block. Although Henrietta did not date her block, it too was probably done in 1849.

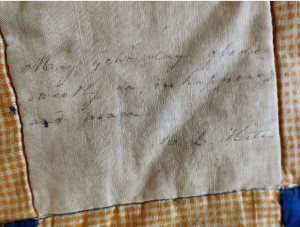

The text in the block shown in Fig. 13 has faded badly, but the verse can be read as follows: “may your days glide/sweetly on, in happiness/and peace.” It is signed by a female with a name that appears to be “M. L. Hite.” If this is a correct reading of the signature, the maker of this block could be Maria Louise Davison, daughter of Maj. William Davison and Maria Smith, who married Isaac Fontaine Hite, Ann T. Hite’s son. The text in the block comes from the final two lines of a poem called “The Bride,” that appeared in a number of early nineteenth century publications. For example, it was published in 1837 in volume one of The Ladies’ Garland, an inexpensive periodical for women, a type of publication that flourished in the 1840s. According to a History of American Magazines: 1741-1850 by Frank Mott, The Ladies’ Garland began publishing in 1837 as a sixteen-page duodecimo, “illustrated with inferior woodcuts,” but “later increased its offering to twenty-four pages and included hand-colored woodcuts of flowers and fashions, with some lithographs.”59 The poem was also set to music as early as 1837 when it appeared in The American Minstrel, a collection of popular songs and other musical forms.”60

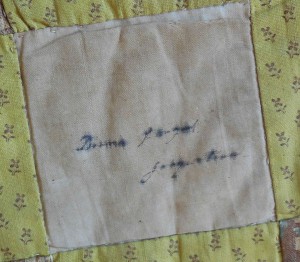

The block shown in Fig. 14 does not incorporate a verse, as do some of the others. Instead it simply says, “Don’t Forget/Jacqueline.” The author of this block cannot be identified although the name Jacquelin (no “e”) does appear in the Hite family. For example, Mary Eltinge Hite, daughter of Ann T. Hite, married John Smith Bull Davison, brother to Maria Louise Davison. Mary Eltinge and her husband had a daughter named Sarah Jaquelin Davison, who was born in 1829, but died as an infant. Perhaps this block was meant as a remembrance of the untimely death of this young child.

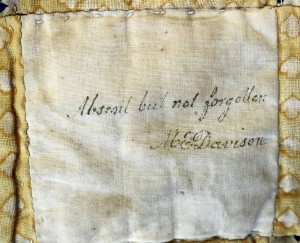

Another simple message appears in the block illustrated in Fig. 15: “Absent but not forgotten/M. E. Davison.” It seems probable that this block was executed by the Mary Eltinge (Hite) Davison mentioned in the previous paragraph. The expression, “Absent, but not forgotten,” can be found in several publications that could have made their way into the hands of Mary Eltinge. One example of the use of this phrase can be found in another magazine produced for women during the 1840s called The Universalist and Ladies’ Repository. It appears in volume eight in a section headed “Characteristics and Necessity of Gospel Hope.”61 The expression, which is part of a large text, reads as follows: “Parent shall gaze on child and child on parent—sister shall greet the long absent, but not forgotten, features of the brother, and the brother shall bless God that he has still sisters left.” Whether this is the source for her inspiration is unknown, but given the timeframe and context, it could be. Mary Eltinge (Hite) Davison died in 1866 and her husband in 1874. Both are buried in the Hite Cemetery at Belle Grove.

A block with a comment similar to that expressed in Fig. 15 is depicted in Fig. 16 and reads: “Absent tho’ not forgot [or, forgotten].” Little can be said about this sentiment other than it was widely used then, as it still is now. The signature of this block appears to be “S. C. M. Bird.” If this is correct, the maker could be Sarah Clark Macon Hite, who married Mark Bird. The maker of the block shown in Fig. 16 created a second block, Fig. 17, and used some of the same blue checkerboard fabric. The signature is identical to that show in the previous block, but the verse in Fig. 17 reads, “Forget me not.”

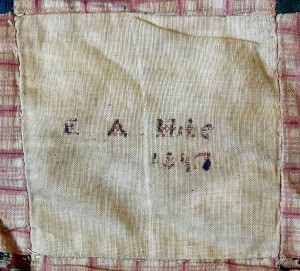

The block shown in Fig. 18 contains only a signature and date: “E. A. Hite/1847.” While it is not proved, this block could be the work of Elizabeth Augusta Smith, who married Cornelius Baldwin Hite, son of Maj. Isaac Hite and Ann T. Hite.62 Elizabeth Augusta was the daughter of Col. Augustin Charles Smith and his wife, Elizabeth Dangerfield Magill.63 Figure 19 is an even simpler block in that it only contains a signature, which appears to be “A. Y. Hite.” A search for a candidate with this name was unsuccessful, but future research may be able to identify its maker.

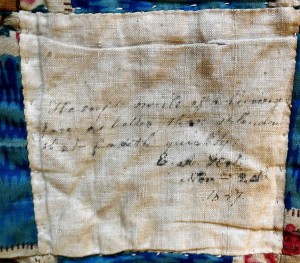

Figure 20 shows another signature block that contains a verse, a signature and a date. The verse has faded badly, but enough of it can be read to identify the other words. It too comes from a poem, this one by the English writer and poet, Martin Farquhar Tupper. Tupper was born in London on July 17, 1810, and died in Albury House, near Guilford, Surry, on November 29, 1889.64 The verse on the quilt reads as follows: “The soft smile of a loving/face is better than splendor/that fadeth quickly.” The poem, which is part of a collection by Tupper called “Of Marriage,” can be found in a collection of his poetical works published in Boston in 1849.65 The date, although rather obscure, seems to read: “Novbr 2d./1847.” The signature of the maker of this block can only be read in part as, “E. A. [illegible].”

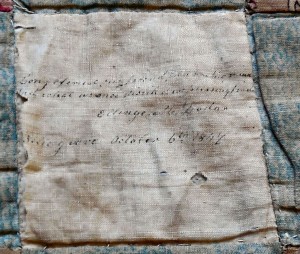

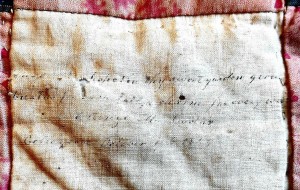

The verse written in the signature block shown in Fig. 21 has deteriorated badly and has yet to be deciphered. However, the signature appears to read, “Eltinge M. Lodor.” It has already been seen that Rebecca Grymes Hite, daughter of Maj. Isaac Hite and his wife, Ann T. Hite, married the Rev. John Loder. Their children included a daughter, Eltinge Mary Loder, who was born at Belle Grove on April 5, 1833. She married in Baltimore, Maryland, October 29, 1856, to George Hinkley. This block is dated “Belle Grove October 6th 1847.” It is likely that Eltinge was still living at Belle Grove when she executed this block. Figure 22 is another block that also appears to have been executed by Eltinge M. Lodor. It too is dated Belle Grove, and although the date itself is very difficult to read, it also seems to be October 6, 1847. Despite the deterioration of the verse, it can be read as follows: “Auspicious Hope! In thy sweet garden grow/Wreaths for each toil, a charm for every woe.” This verse comes from a poem by Scottish poet, Thomas Campbell, who was born July 27, 1777, and died June 15, 1844. The complete poem is called “The Pleasures of Hope,” and can be found in a compilation of British poets published in 1824.66

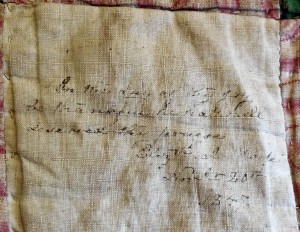

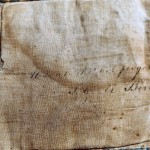

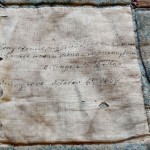

Of the remaining quilt blocks, two can be read, but only in part. First, the inscription in Fig. 23 reads, “Absent though/not forgotten.” It is signed but the signature is illegible, although it looks a bit like “Loder”. In Fig. 24, the second of these blocks has a verse that extends to three lines, but only a few words can be read. This is frustrating because it appears to begin with something like “In this day of” and the last word (first line) could be “joy”. The words in lines two and three cannot be deciphered. This last block is signed by a maker whose name appears to be “Elizabeth A. Hite”, but this interpretation is uncertain. It is also dated, and the date appears to read, “Nov 20th/1847.” Perhaps with better technology, the texts in these two blocks can be properly deciphered.

As stated earlier, the Old Mansion quilt is in a poor state of preservation. This is probably not surprising given its 170-year history that includes, among other things, surviving the Civil War; many southern quilts were destroyed during the war when they were cut up to make bandages for the wounded or sent off to war with those who did the fighting. Others were lost in the many conflagrations brought about by the conflict. Despite its condition, it is considered to be an important historical object, a survivor that tells a story that interconnects not only two of Virginia’s important early homes, but the families that lived and died in them.

Published on: Oct 6, 2015

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

- Figure 24

Endnotes:

1 The spelling Hoomes is used here but, in some records, the name is seen as Holmes and in other similar phonetic variants.

2 Campbell, Thomas E. Colonial Caroline, A History of Caroline County, Virginia. Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, Inc., 1954, pp. 294, 296.

3 Harris, Malcolm Hart. Old New Kent County, Some Account of the Planters, Plantations and Places in New Kent County. West Point, VA: Malcolm Hart Harris, 1977. Vol. I, p. 349.

4 Campbell, Colonial Caroline, p. 450.

5 Ibid., p. 353.

6 Ibid., p. 346.

7 Ibid., p. 347.

8 Hall, Wilmer L., ed. Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, Vol. V (November 1, 1739-May 7, 1754). Second Edition. Richmond, VA: Virginia State Library, 1967, p. 390.

9 Campbell, Colonial Caroline, p. 399.

10 “A Merchant’s Account Book, King and Queen County, Virginia, 1750-1751,” transcribed by Richard Slatten. The Virginia Genealogical Society. Virginia Genealogical Society Quarterly and Magazine of Virginia Genealogy, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 67,146, 228, 301, 304.

11 Campbell, Colonial Caroline, p. 474.

12 Ibid., n17.

13 Hoomes family Bible records (1734-1894). Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA, Mss 6:4 H7655:1.

14 Morris, Whitmore. The First Tunstalls in Virginia and Some of Their Descendants. San Antonio, TX: Clegg Co., 1950, p. 228.

15 Harris. Old New Kent County. Vol. I, p. 23.

16 Campbell, Colonial Caroline, p. 413.

17 Ibid., p.348.

18 Ibid. p. 434.

19 “To George Washington from John Hoomes, 16 August 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0126 [last update: 2015-03-20]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, Vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 263–268, and footnotes.

20 Ibid.

21 Hopkins, William Lindsay. Caroline County court records and marriages, 1787-1810. Richmond, VA: R. L. Hopkins, 1987, p. 186.

22 Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Richmond, VA. Vol. 38 (1930), pp. 74-79. An obituary for George Washington Hoomes can be found in the July 31, 1802 issue of the Virginia Argus and refers to him as the “second son of Col. John Hoomes of the Bowling Green.”

23 Hopkins, Caroline County court records and marriages, p. 52.

24 “Dickinson vs. Hoomes’s adm’r, & als.” Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, Vol. 49. Richmond, VA: T. Nicholson, 1852, pp. 354-441.

25 Old Mansion cemetery records, accessed via Find A Grave available

online at http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gsr&GScid=2434562.

26 Hopkins, Caroline County court records and marriages, p. 139.

27 Bowling Green Historic District, Caroline County, Virginia, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form NRHP 5/22/03, p. 56, available online at http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Counties/Caroline/NR_Caroline_BowlingGreenHD_171-5001_Text.pdf.

28 “Plat, 1824 August [?], of 2,694 acres covering “Bowling Green,” Caroline County, Va., surveyed for Sophia (Hoomes) Allen, Armistead Hoomes, John Waller Hoomes, and the heirs of Richard Hoomes,” Virginia Historical Society manuscript MSS11:3 H7655:1.

29 Hoomes family Bible records (1734-1894).

30 Wingfield, Marshall. A History of Caroline County, Virginia: from its formation in 1727 to 1924. Richmond, VA: Press of Trewet Christian & Co., 1924, p. 356.

31 Old Mansion, Bowling Green, Virginia, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, #69000227, dated November 12, 1969.

32 Miles, D. H., and Michael J. Worthington, “The Tree-Ring Dating of Old Mansion, Bowling Green, Virginia,” ODL unpublished report 2006/52 Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory Interim Report 2008/05.

33 Jackson, Donald, and Dorothy Twohig, ed. The Diaries of George Washington. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1979, Vol. 6, p. 108.

34 Wingfield, A History of Caroline County, p. 358. Also see Sarah A. Trautvetts, “A History of Change in the Virginia Landscape,” a presentation to the Garden Club of Virginia at Old Mansion, Summer 2002.

35 “The Maury Family – A Brief History,” available online at http://www.fontainemaurysociety.com/mauryhistory.html.

36 Du Bellet, Louise Pecquet. Some Prominent Virginia Families. Vol. 4., Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell Co., 1907, pp. 397-398.

37 O’Dell, Cecil. Pioneers of Old Frederick County, Virginia. Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing Company, 1995, pp. 17-19.

38 Ibid., p. 20.

39 “Belle Grove,” Special Issue on Belle Grove, Magazine of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Vol. 20, Nos. 3-4, July-December, 1968, pp. 7-8.

40 Wayland, John Walter. The German Element of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: The Michie Company, Printers, 1907, p. 51.

41 “Memo. Copied from the note-book of Major Isaac Hite, Jr. (born February 7, 1758; died November 24, 1836), of “Belle Grove,” Frederick County, Va.,” Genealogies of Virginia Families From the William and Mary Quarterly Historical Magazine, Vol. V, Thompson—Yates (and Appendix), pp. 926-930.

42 Du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families, Vol. 4, p. 398. Also see Cartmell, T. K. Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants, A History of Frederick County, Virginia. Winchester, VA: The Eddy Press Corp., 1909, p. 257.

43 Ibid.

44 “The Woolfolk Family Papers, 1775-1893,” Manuscripts Department, Earl Greg Swem Library, William and Mary College, MSS. 39.1 W88.

45 Randolph, Robert Isham. The Randolphs of Virginia, a compilation of the descendants of William Randolph of Turkey Island, and his wife Mary Isham of Bermuda hundred. Chicago: IL:n.p., ?1936, p. 249.

46 West, Sue Crabtree, comp. The Maury family tree: descendants of Mary Anne Fontaine (1690-1755), Matthew Maury (1686-1752) and others. Birmingham, AL: Sue Crabtree West, 1971, p. 153.

47 Randolph, The Randolphs of Virginia, p. 249.

48 West, The Maury family tree, p. 153.

49 Collins, Herbert Ridgeway. Caroline County, Virginia Death Records (1919-1994) from The Caroline Progress, A Weekly Newspaper Published in Bowling Green, Virginia. Westminster, MD: Family Line Publications, 1995, p. 171.

50 Sarah A. Trautvetter, “Old Mansion: A History of Change in the Virginia Landscape,” a presentation to the Garden Club of Virginia at Old Mansion, Summer 2002.

51 Pension file S8714, Hite, Isaac, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (NARA microfilm publication M804, 2,670 rolls). Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

52 Duppa, Richard. Maxims, Reflections, &c. London: Longman and Co. Paternoster Row, 1830, p. 38.

53 Odd Fellows’ Magazine of the Manchester Unity of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, New Series, Second Edition, Manchester: Mark Wardle, 1829, p. 59.

54 Brackman, Barbara. Clues in the Calico: A Guide to Identifying and Dating Antique Quilts. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1989, p. 20.

55 Ibid.

56 Kelley, Helen, Lee Sandberg and Greg Vinter. Minnesota Quilts: Creating Connections with Our past. Stillwater, MN: Voyager, 2004, N. pag.

57 Genealogies of Virginia Families From the William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. Vol. IV, indexed by Judith McGhan. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., 1982, p. 602.

58 Moore, Thomas. The Poetical Works of Thomas Moore, Including Melodies, Ballads, Etc. Philadelphia, PA: J. Crissy, 1835, pp. ix, 377.

59 Mott, Frank Luther. History of American Magazines: 1741-1850. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930, p. 68.

60 James, J. A. The American Minstrel, A Choice Collect ion of the Most Popular Songs, Glees, Duets, Choruses, &c. Cincinnati, OH: J. A. James and Co., 1837, p. 296.

61 Bacon, Rev. Henry and Miss S. C. Edgerton, eds. The Universalist and Ladies Repository. Vol. VIII, Boston, MA: A. Tompkins, 1840, p. 460.

62 Du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families, Vol. 4, p. 398.

63 Paxton, William McClung. The Marshall Family: Or A Genealogical Chart of the Descendants of John Marshall and Elizabeth Markham, His Wife. Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co., 1885, p. 142.

64 Gluck, James Fraser, and Theresa West Elmendorf. Descriptive catalogue of the Gluck collection of manuscripts and autographs in the Buffalo public library. Buffalo, NY: The Matthews-Northrup Co., 1899, p. 116.

65 Tupper, Martin Farquhar. Tupper’s Poetical Works: Proverbial Philosophy, A Thousand Lines, Hactenus: With a Portrait of the Author. Boston, MA: Charles H. Peirce, 1849, p. 117.

66 Hazlitt, William, and William Wordsworth. Select British Poets, Or, New Elegant Extracts from Chaucer to the Present Time, with Critical Remarks. London: William C. Hall, 1824, p. 577.