By Michael L. Marshall

Introduction

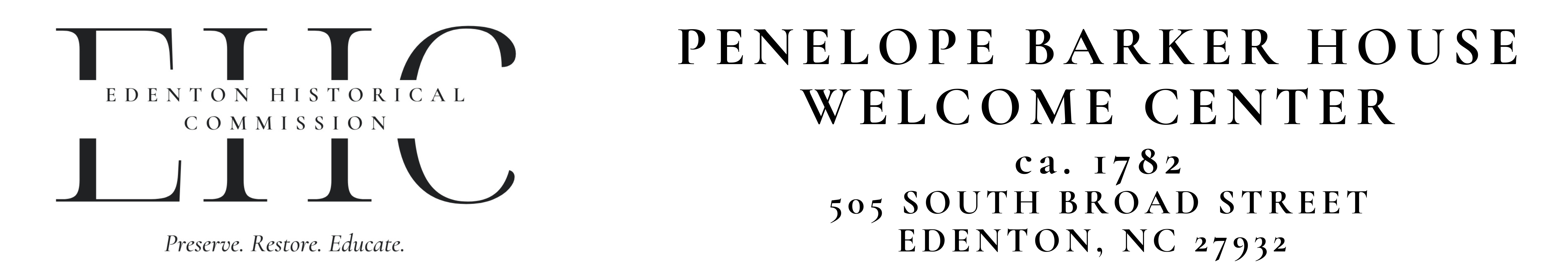

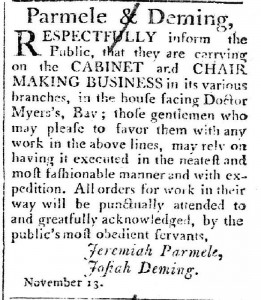

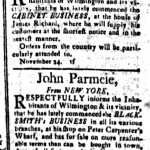

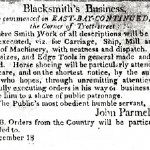

John Bivins, Jr., in his now classic volume, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700-1820, included an entry for a cabinetmaker identified as Samuel Parmele1 of New York City and Wilmington, North Carolina.2 Bivins’ description of Parmele reads: “The Wilmington Gazette for 25 Nov. 1806 carried two advertisements, one for John Parmele, blacksmith, from New York, and the other for ‘Samuel Parmele, From New-York,’ who ‘RESPECTFULLY informs the inhabitants of Wilmington and its vicinity, that he has lately commenced the CABINET BUSINESS, at the house of James Richard, where he will supply his customers at the shortest notice and in the neatest manner.’ A year later, ‘JEREMIAH PARMELLE [sic], FROM THE NORTHWARD, CABINET MAKER,’ placed an advertisement in the Petersburg Intelligencer for 29 Dec. 1807, stating that he was establishing his business in that city. The relationship, if any, is not known.” (Fig. 1, Advertisement placed in the December 2, 1806 issue of the Wilmington Gazette by Samuel and John Parmele).

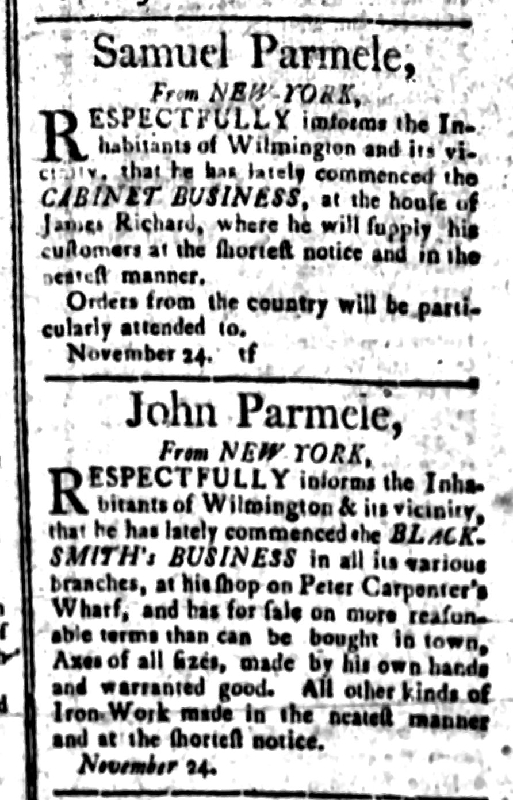

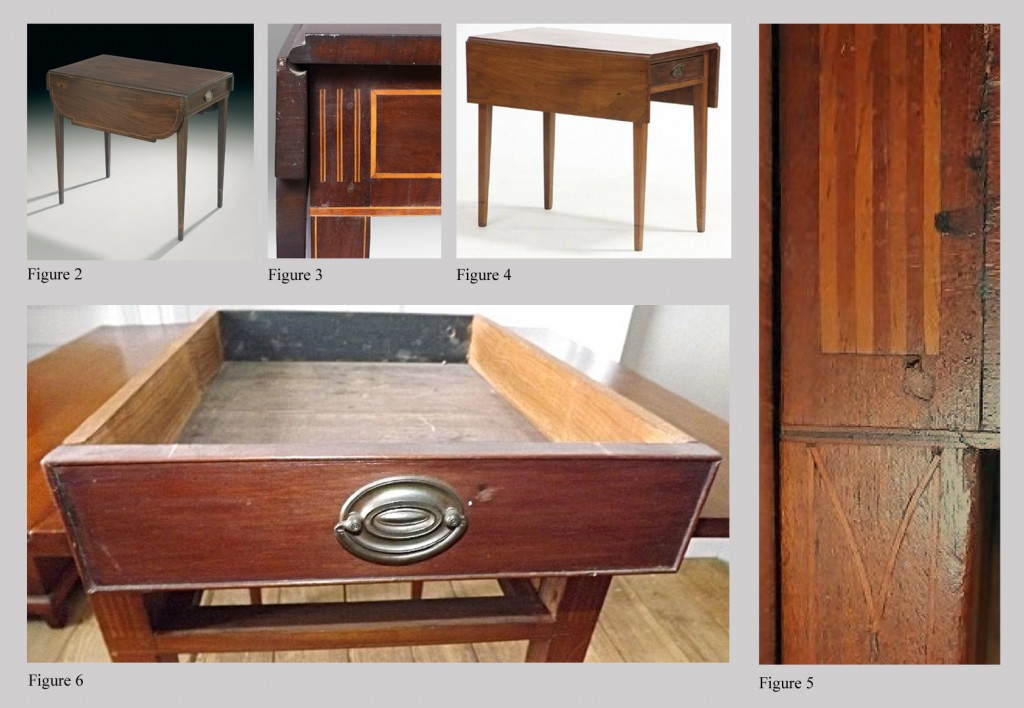

Only one signed piece of furniture attributed to Samuel Parmele has been discovered thus far. It is a Pembroke table that sold at a catalog auction conducted by the New Orleans Auction Galleries, New Orleans, Louisiana, in July of 2012 (Fig. 2, Signed Samuel Parmele Pembroke table. Courtesy New Orleans Auction Galleries), (Fig. 3, Detail of Fig. 2 showing parallel line inlay on table. Courtesy New Orleans Auction Galleries).3 The catalog for the sale described the table as follows: “American Federal Line-Strung Mahogany Pembroke Table, ca. 1800, stamped ‘S Parmele,’ for Samuel Parmele of New York and Wilmington, North Carolina, the top flanked by drop leaves with perimeter string banding, over a frieze fitted with a single end drawer, raised on the square tapering legs capped with a trio of parallel inlaid lines and with stringing down the tapering legs to the cuffs, the knuckled gate with the incised stamp ‘S Parmele,’ retains its period drawer pull. Construction: Pine case and drawer secondary woods, cherry gate mechanism h. 29″, w. 30-3/4″, d. 18-3/4″.” The catalog description also observed that Samuel’s brother, John Parmele, was a blacksmith, which prompted this further comment: “That Samuel chose to stamp this piece with an iron punch is consistent with a family member who was an ironworker.” Finally, noting that the table’s tapering legs were “capped with a trio of parallel lines,” the cataloger for this entry observed that “The use of three similar lines of parallel inlay on an unattributed Wilmington piece is illustrated in Bivens, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700-1820 plate 7.44a.” In fact, the table illustrated in Bivins as plate 7.44 is one of a pair of card tables attributed to the same shop as a desk also illustrated in Bivins as plate 7.38.4 These tables have ovolo ends, sometimes referred to as a “sash” shape in some early inventories because the profile is similar to that of window-sash mullion. Only one other southern Pembroke table with parallel line inlay on the apron, capping the straight tapered legs, has come to light. It was reportedly recovered in Perquimans County, North Carolina, (Fig. 4, Eastern North Carolina Pembroke Table. Private collection, used by permission), (Fig. 5 Detail of Fig. 4 showing parallel line inlay. Private collection, used by permission). The straight tapered legs are decorated with string inlay and cuff banding and the single drawer has cock beading (Fig. 6, Detail of Fig. 4 showing drawer with cock beading. Private collection, used by permission). The table is 30.5″ long, stands 27″ high, and has a width of 18″ with its leaves down (leaves are 8.75″). It is a much simpler table than the one by Samuel Parmele and certainly not as finely executed.

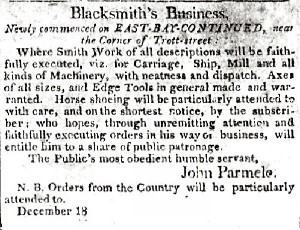

Beyond the advertisements that ran several times in the Wilmington Gazette in November and December 1806, there is no further mention of Samuel Parmele in Wilmington. There is, however, a list of letters in the post office of that city that appeared in the July 21, 1807 issue of the same newspaper and it included the name John Parmele. This may be an indication he and Samuel had already left the area by that date. There is a possibility that John departed Wilmington for Charleston, South Carolina, and may be the man who ran a notice in the December 18, 1807 issue of the City Gazette and Daily Advertiser of Charleston advertising his blacksmith business (Fig. 7, Copy of John Parmele advertisement in the December 18, 1807 Charleston, South Carolina, City Gazette and Daily Advertiser). The advertisement announced that his business was “Newly commenced on EAST-BAY-CONTINUED, near the Corner of Trott-street. Where Smith work of all descriptions will be faithfully executed, viz. for Carriage, Ship, Mill and all kinds of Machinery, with neatness and dispatch.” John Parmele’s Charleston advertisement also contained a phrase identical in construction to one that appeared in the Samuel Parmele notice in the Wilmington Gazette: “Orders from the County will be particularly attended to.”

As mentioned by Bivins, another cabinetmaker named Parmele appeared in a newspaper advertisement in the Petersburg Intelligencer, Petersburg, Virginia, in 1807, the year after Samuel and John advertised in Wilmington.5 According to its wording “JEREMIAH PARMELLE [sic] FROM THE NORTHWARD, CABINET MAKER, Respectfully informs the citizens of Petersburg and its vicinity, that he has taken the house opposite the Bank, lately occupied by Thomas Lorain, in Bollingbrook street, where he is carrying on the above business in all its branches—he trusts that the competent knowledge he has of the trade, and attention to all his duties, will ensure him ample encouragement.” It seems Jeremiah was still in Petersburg in May of 1808 according to a record found in the Petersburg Hustings Court Minute book for 1805-1808.6 It states that a grand jury presented “Jeremiah Parmele, Cabinet maker for Drawing a Lottery at the tavern of Robert Nicholson. On 26 Mch [March] 1808 & receiving payment for sd. Lottery to amount $750.”7 At the same time the jury also presented an indictment against “Robert Nicholson Tavern Keeper for suffering a lottery to be drawn at his tavern ‘for the benefit of Jeremiah Parmele on 26 March 1808.’”8 The outcome of these legal proceedings is unknown; however, as there is no further mention of Parmele in Petersburg, he may have returned to the “northward” following his brush with the law in Virginia.

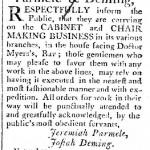

One final mention of a Jeremiah Parmele, cabinetmaker, has been found thus far among the records of the southern states. It comes from a newspaper advertisement that ran in the Georgetown Gazette of South Carolina on November 13, 20, 27 and December 3, 10, 1799 (Fig. 8, November 13, 1799 Georgetown Gazette advertising the partnership of Jeremiah Parmele & Josiah Deming, cabinet and chair makers). As such, it predates the appearance of Samuel and John Parmele in Wilmington in 1806 and Jeremiah Parmele in Petersburg in 1807. The notice read: “Parmele & Deming, Respectfully inform the Public, that they are carrying on the CABINET and CHAIR MAKING BUSINESS, in the house facing Doctor Myers’s, [on the] Bay; those gentlemen who may please to favor them with any work in the above lines, may rely on having it executed in the neatest and most fashionable manner and with expedition. All orders for work in their way will be punctually attended to and greatfully [sic] acknowledged, by the public’s most obedient servants, Jeremiah Parmele, Josiah Deming.” Established in the 1720s and declared an official port of entry in 1731 (making it the third oldest town in South Carolina after Charleston and Beaufort), Georgetown and surrounding vicinity had a population of more than 5,000 free citizens by 1790. It was also ideally suited as a seaport due to its location on Winyah Bay, at the confluence of the Black, Great Pee Dee, Waccamaw, and Sampit Rivers. While indigo had brought great wealth to the planters who lived on the rivers around Georgetown in the mid-eighteenth century, it was rice that contributed to their affluence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and they no doubt provided a ready market for quality cabinet and other fashionable goods. In fact, the records reveal the presence of several cabinetmakers who worked in Georgetown during this period.9 They included Thomas Blythe (1734-1762), Robert Durant (1766), John Packrow (1767-1777), John Oxenham (with John Packrow, 1774), Peter Cooper (1812), Thomas Dowdney (1809-1813), John B. McDaniel (1817-1819), Robert McKildoe (1806-1807), Edmund Morris (1819), and James Rembert (1810). Colonial Williamsburg has in its collection a Hepplewhite sideboard dating to 1795-1810 that is attributed to Georgetown based on its history of ownership in a family there and its strong similarities to another sideboard that descended in the Alston family of nearby Brookgreen and Chicora plantations (MESDA accession 950-5).10

Parmele & Deming’s 1799 advertisement in Georgetown is interesting for two reasons. First, it indicates that the co-partners were offering themselves not only as cabinetmakers, but also as chair makers. Secondly, it associates Jeremiah Parmele with the Deming name, an old Wethersfield, Connecticut family that produced several important cabinetmakers, including Simeon Deming (Mills & Deming, New York City), Barzillai Deming (Deming & Bulkley, New York City and Charleston, South Carolina), and others. The Deming connection will be discussed again later.

While this paper will identify Jeremiah and Samuel Parmele, interesting questions that cannot be answered on the basis of presently known facts are, why did Jeremiah and Samuel venture into the South, and why did they not remain there very long when they did? They were certainly not the only northern artisans to make only transient appearances in the South, especially in coastal towns along the Atlantic. In Wilmington Furniture, 1720-1760, it is stated that one characteristic of the cabinet trade there was the constant arrival of artisans from elsewhere: “England, New England, New York, Virginia, and Charleston, all provided the Cape Fear with new talent.”11 Some cabinetmakers traveled from city to city seeking favorable custom and while most remained in one place for at least a year or two, this was not always the case. Indeed, during the early years of the nineteenth century, many northern artisans made regular swings through the South seeking business.12

Forsyth Alexander has studied in detail the cabinet trade in southern Atlantic ports during the last quarter of the eighteen and the first quarter of the nineteenth centuries and written about its trends, especially cabinet warehousing.13 According to Alexander, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston had developed large furniture-making centers and the proprietors of these centers “viewed the South as a large new market for their fashionable work.”14 Some northern cabinetmakers made furniture to be sold as venture cargo in the southern colonies: “The furniture either was displayed and sold by cabinetmakers, or more commonly, by shippers, consignment merchants, and vendue masters.”15 Before the Revolution, most of these consignments were small but afterwards, large shipments were often made. In some instances, northern cabinetmakers “even traveled with their furniture to the south, particularly after 1790; some of these cabinetmakers often only remained there long enough to sell one shipment, and others journeyed back and forth for several years.”16

Philadelphia Windsor chairs and New York furniture, among other northern goods, found eager markets in southern ports, including those in North and South Carolina. In Edenton, “Elegant Cabinet Work,” was advertised by “C. W. Janson, From Boston,” in 1796.17 Wilmington, too, was a market for northern cabinet wares. On October 26, 1788, Christopher Ellery of Wilmington advertised that he had just imported in the brig Recovery a number of goods, including maple desks; the Recovery had sailed from Rhode Island.18 A notice in the Wilmington Gazette of October 15, 1805 offered for sale “A VARIETY OF PHILADELPHIA FURNITURE” received from the Brig Esparanta.19

Georgetown, South Carolina was also a destination for northern artisans and finished northern goods. Painter and glazier, James Michaels, advertised in the November 27, 1798 Georgetown Gazette that “he has lately arrived from Philadelphia, and intends carrying on the PAINTING and GLAZING BUSINESS, in Georgetown, in all its branches.” In the June 11, 1791 issue of the Georgetown’s South-Carolina Independent Gazette, merchant David Prior advertised a long list of articles for sale “at his store on the Bay, on the most reasonable terms,” including “a neat eight-day mahogany clock, a mahogany bureau, &c.” In the December 25, 1799 issue of the Georgetown Gazette, Reuben Mathews “On the Bay” informed the public that “he has for sale, A FEW DOZEN OF GREEN CHAIRS that he will sell low for Cash, as he is positively to remove to Charleston in ten days from this date.” The term “green chair” was used at the time as the street name for Windsor chair, as many of them were painted that color. In the February 15, 1804 issue of the same newspaper, merchant John Taylor of Georgetown announced he had for sale, by the schooner Lucy, Capt. Lawson, from New York, “20 cases MAHOGANY FURNITURE.” Others were also warehousing furniture there including Robert McKildoe, a Georgetown cabinetmaker and upholsterer “On the Bay, opposite Mr. Mathew’s Tavern.” In his notice in the June 20, 1807 Georgetown Gazette, and Commercial Advertiser, he sought to acquaint all his friends and the community at large that “At his Ware Room, may be seen & had every kind of Cabinet & Upholstery work, on the most reasonable terms.”20

In Wilmington, Charleston, Savannah, and elsewhere in the coastal south, “no small degree of the New York mode” was embraced by southern cabinetmakers “because of the actual emigration of New York artisans in addition to imported finish work.”21 Perhaps it was the growing taste in the South for New York styles and the shipping of finished cabinet goods from New York and other northern cities that suggested to both Jeremiah and Samuel Parmele that the South might be an attractive place to locate their cabinet businesses, or to target for northern imported furniture.

Joseph Parmele of Branford

So, who were Jeremiah and Samuel Parmele? While there is always room for additional research, it is believed there is sufficient evidence to suggest that the Samuel, John, and Jeremiah Parmele, who appear in the records of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, were brothers, and sons of Joseph Parmele who lived and died in Branford, Connecticut.

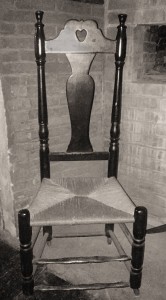

The Parmele family came to the New Haven Colony in the early seventeenth century, seating themselves in Guilford, Branford, and in other nearby locations. According to data collected by the Connecticut Historical Society museum and library, the Guilford line of this family included several early craftsmen, for example, turner Isaac Parmele (1665-1748/49); clockmaker and turner Ebenezer Parmele (1690-1777); turner Anna Parmele (1690-1790); turner Isaac Parmele (1702-1752); turner Josiah Parmele (1709-1739); and turner Ebenezer Parmele II (1738-1802).22 The Society’s collection contains a side chair originally owned by Ebenezer Benton (1663-1758) (Object Number: 2006.30.2) that was made by a member of this family.23 This Guilford line is especially known for its black painted “Heart and Crown” chairs, so called because of the distinctive shape of their backs (Fig. 9, Heart and Crown chair attributed to the Parmele family of Guilford. Private collection, used by permission). A pair of these side chairs was sold by Skinner in an auction of American furniture and decorative arts held on November 7, 2010 (Lot # 173).24 The oldest surviving Connecticut public clock was made by Ebenezer Parmele in 1726 for the First Church and Society of Guilford; it is now located in the Henry Whitfield State Museum in Guilford.25

Joseph Parmele, born 1738, was the son of Timothy Parmele of Branford and his wife, Desire Barnes.26 On December 1, 1763, Joseph married Sarah Howd. The ceremony was performed in the Branford Congregational Church by the Rev. Philemon Robbins.27 The couple had eight children: sons, Timothy, John, Jeremiah, and Samuel, and daughters, Sarah, Hannah, Margaret, and Amelia.28 Vital record data concerning Joseph’s sons are compiled in volume two of the series by Alvan Talcott, Families of Early Guilford.29 Sons Jeremiah, Samuel, and John are discussed later in more detail. Joseph’s other son, Timothy Parmele, was born October 25, 1764 and died October 1791, lost in the Sloop “Hawk.”30 He lived in Branford, where he married Matty Norton on October 4, 1788; their two sons, John and Timothy, like their father, were also lost at sea.31

Joseph Parmele penned his will on January 23, 1799.32 According to its terms, he devised both real and personal property to his wife, Sarah; grandsons John and Timothy, sons of deceased son, Timothy; daughters Sarah, Hannah, Margaret, and Amelia; and to his living sons, John, Jeremiah, and Samuel. Joseph lived for several years after making his will before finally passing away on November 20, 1807. He was laid to rest in the Old Burying Ground located just northeast of Bradford’s village green where his gravestone, still standing, bears the following epithet: “In Memory of Capt. Joseph Parmele who died Nov. 20, 1807 Aged 70 Years.”33 His widow, Sarah, was appointed by the Court of Probate for the Guilford district on December 14, 1807 to administer his estate, and a legal notice of the appointment and notice to creditors was published in the December 29, 1807 issue of the Connecticut Herald, and in subsequent issues of the same paper. Several months later, on May 2, 1808, his wife and son, John, produced his will along with an inventory and account for Joseph’s estate in a court held in Branford.34 The probate papers reveal that son Jeremiah sold his share of his father’s estate to his brothers, John and Samuel.

Jeremiah Parmele

Joseph’s son Jeremiah is believed to be the cabinetmaker that appeared briefly in November and December, 1799, in a newspaper advertisement in the Georgetown Gazette, along with Josiah Deming, and in 1806 and 1807 in Petersburg, Virginia, records. No signed pieces of furniture that can be attributed to him have been found. As will be presently seen, Jeremiah spent most of his years in Connecticut, but moved to New York City around 1825 or 1826.

Jeremiah was born in Branford, Connecticut on February 14, 1777.35 As Jeremiah Parmele of “Branford” he married Helen Vail of Guilford on January 4, 1796, the marriage being performed by the Rev. Amos Fowler of the First Congregational Church of Guilford.36 Helen was the daughter of Capt. Jonathan Vail, a Revolutionary officer who, as captain of a ship, was active with his brother Capt. John Vail in transporting refugees in 1776 from Long Island to Guilford, following the invasion of New York by the British.37 Born September 16, 1736 at Southold, Long Island, New York, Jonathan Vail married on May 3, 1757 to Hannah Horton of Southold.38 In 1775 Jonathan and his family left New York and moved across Long Island Sound to Guilford where their nine children were born: Seth Vail (1757-1780); Hannah (1760-1835); Jonathan, born October 18, 1762, died September 11, 1844, of whom more will be said later; William (1765-1784); Lydia (1767-1853); Phebe (1770-1807); Joshua (1774-1802); Helen, born November 1, 1776, died January 15, 1858; and Sally (1779-1805).39

According to Vail family records Jeremiah and Helen had eight children: Almera Parmele, born September 16, 1797; Horatio Parmele, born February 6, 1804; Jeremiah Osmer Parmele, born September 18, 1805; Edwin Parmele, born December 5, 1813, Sarah Vail Parmele, born July 19, 1816; Horton J. Parmele (twin), born July 19, 1816; and Helen Parmele (twin), born July 19, 1816.40 In later years Jeremiah’s son Edwin resided in Guilford where he died unmarried on August 30, 1852.41 Sons Jeremiah Osmer and Horton J. Parmele lived in New Haven; the former died there on February 7, 1854, and Horton J. on March 9, 1855.42 Horatio, seen in most records as Horatio N. Parmele, became a cabinetmaker. He married Rosetta Ames and they resided in New York City.43 More will be said about him shortly.

If Jeremiah were in Georgetown, South Carolina in late 1799, he must have left soon after advertising his partnership with Josiah Deming as no further record of his presence there has been found. In fact, it appears he moved back to Connecticut and is probably the man of that name found on the 1800 Federal census of Guilford, Connecticut. The ages given for members of his household seem to fit his family. Moreover, Jeremiah’s name appears in the original census record written on the same page as those of Samuel Parmele and Jonathan Vail, very probably his brother and father-in-law, respectively.44 His name is listed again in the Federal census taken for Guilford in 1810 and he was still there when the 1820 census was taken.45

In 1808 Jeremiah’s name appeared among the records of the Connecticut State Militia as an Ensign.46 In May of 1812 the State Assembly appointed “Jeremiah Parmele Esquire, a Major in the 27th Regiment of the Militia of the State.”47 He had risen to the rank of Captain by the following year.48 He continued to be listed as a member of the militia in later volumes of Samuel Green’s Connecticut Annual Register And United States Calendar, which show that he rose rapidly through the ranks. He must have been a man of substantial reputation because in 1819 the Connecticut State Assembly appointed “Jeremiah Parmele Esquire, Brigadier General of the 2d Brigade of militia in this state.49 A notice of his appointment was published in the August 17, 1819 issue of the Times of Hartford, Connecticut. He continued at this rank through 1822. However, in a “list of Military Resignations accepted, and Appointments made by the Legislature, at their session in 1823,” published June 24, 1823 by the Connecticut Herald, the name “Jeremiah Parmelee [sic], Brigadier General 2d Brigade Infantry” is counted among those officers who resigned their rank. He was forty-six years old at the time.

No further mention of Jeremiah has been found in the Connecticut records after this date. His name, though, appears in Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register and City Directory printed in 1826 and covering the period, 1826-27.50 The listing called him Jeremiah Parmley [sic] and identified him as a “cabinet maker” with an address on Charles Street, north of Factory. This same directory also listed Horatio N. Parmele as a “cabinet maker” and gave his address as 10 Bancker Street. Directories for the two previous years, i.e., for 1823-2451 and 1825-2652 were also examined, but they do not mention either Jeremiah or Horatio. It will be recalled that Horatio was born in 1804. If we assume he was trained as a cabinetmaker beginning around the age of fourteen and ending when he was twenty-one, this would suggest he became a journeyman cabinetmaker around 1825 or 1826. It may be that Horatio received his training in New York City and remained there after he was free of his indenture, where he was joined by his father, Jeremiah, but this is not proved.

Other editions of Longworth’s directory were also examined, including the one for 1827-28. It still recorded Horatio N. Parmele as a cabinetmaker but his address there was given as 50 Chrystie Street, which is on the lower east side of Manhattan.53 However, there is no entry for Jeremiah in this directory or subsequent ones. The directory for 1829-30 also listed Horatio N. Parmele as a cabinetmaker, but his address had changed again, this time to 17 Harman Street.54 More importantly, this directory had a listing for Helen Parmele who is called “widow of Jeremiah” and gave her address as 2 Chrystie Street.55 Horatio continued to appear in Longworth’s directories for 1834-3556 and 1835-3657 but he is not listed in the directory for 1836-3758 or thereafter. Whether he died or moved away is unknown as no record of his death has been found.

From the above it seems likely that Jeremiah died some time after 1826, when the directory for 1826-27 was published, and before the subsequent directory was published in 1827. The only record that has been found for a Jeremiah Parmele who died around this time is an obituary that was published in numerous New York City and Connecticut newspapers. One of these was the July 31, 1827 issue of the National Advocate of the city: “DIED, On the 19th of July, at Fallsburgh [sic], State of New York, Gen. Jeremiah Parmele, aged 50 years, formerly of Guilford, Connecticut.” This age would suggest a date of birth in 1777 which coincides exactly with that of the Jeremiah Parmele, son of Joseph and Sarah, who in later life achieved the rank of Brigadier General in the Connecticut State Militia. What Jeremiah was doing in Fallsburg is unknown. In the Victorian era this town in the Catskill Mountains became known for its many resorts. Perhaps Jeremiah was ill and left New York City for a healthier climate, but this is only conjecture.

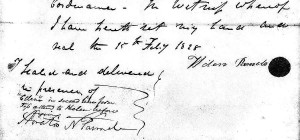

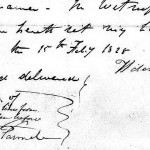

The probate records of New York City contain a renunciation by Helen Parmele of the administration of her husband’s estate.59 The document which she signed read as follows: “Know all men by these presents that Helen Parmele widow of Jeremiah Parmele late of said city, cabinet maker, do hereby renounce my rights to take out Letters of Administration on the Estate of my deceased husband and do pray that [the court] grant the same unto Asa Taylor of said city [his occupation illegible].” The renunciation was signed by Helen on February 15, 1828 and acknowledged before the court on February 18, 1828. The witness to the renunciation was her son, Horatio N. Parmele (Fig. 10, Signatures of Helen and Horatio N. Parmele on renunciation as administrator of Jeremiah Parmele). The same day that the document was acknowledged the court granted Asa Taylor authority to administer the estate of Jeremiah Parmele “late of the city of New York, cabinet maker, Deceased.”60 The relationship of Jeremiah Parmele or his widow Helen to Asa Taylor is unknown. However, it is evident from various newspaper notices and business directories that Taylor operated a tavern that was located at the corner of Broadway and Prince Streets which is believed to be the establishment he called the Columbian Garden in an advertisement placed in the June 27, 1820 issue of the National Advocate for the Country, a New York City newspaper: “The proprietor respectfully informs the public, that, by the encouragement of his friends, he has improved and embellished it so that it may be considered as one of the most airy and pleasant situations in the city. It is now open for the reception and accommodation of visitors . . . The house has been put in good order, by being thoroughly cleaned and painted; and it is designed by the subscriber to accommodate a few genteel Boarders at moderate terms.” Also of possible interest is that in Longworth’s directory for 1827-28 there is a listing for Asa Taylor at 30 Chrystie Street. This is not far from the address in the same directory given for Horatio N. Parmele, which was 50 Chrystie.61 Recall also that Helen Parmele’s address was given as 2 Chrystie Street in Longworth’s 1829-30 New York directory. In any case, following his appointment as administrator of Jeremiah Parmele’s estate, Asa Taylor began placing legal notices in the Evening Post of New York City; the first ran in the May 30, 1828 issue and the last on July 2, 1828. The notice was worded as follows: “CITY & COUNTY OF NEW YORK, SS,–Surrogate’s Office.—Whereas, Asa Taylor, Administrator of all and singular the goods, chattels and credits which were of Jeremiah Parmele, late of the city of New-York, deceased, hath by his petition, presented to James Campbell, Surrogate of the City and County, aforesaid, set forth that the personal estate of the said deceased is insufficient to pay his debts, and requested the aid of the Surrogate in the premises: Notice is hereby given to all persons interested in the estate of the said deceased, to show cause before the said Surrogate at his office in the City Hall of the said city, on Saturday, the fifth day of July next ensuing, why so much of the real estate, whereof the said Jeremiah Parmele died seized, should not be sold as will be sufficient to pay his debts.” The document referenced in this advertisement was dated May 27, 1828 by the Surrogate. As it turned out, Taylor was unable to complete the administration of Parmele’s estate because he died in January of 1829 according to a notice of his death that was carried in the January 22, 1829 Evening Post of that city: “DIED, Last evening Mr. Asa Taylor, in the 50th year of his age. His friends and acquaintance are requested to attend his funeral on Friday afternoon at half past two o’clock from his late residence, 68 Grand st.”

Not long after Asa Taylor’s death one Rhesa Griffin appeared in the city’s Surrogate Court to apply for letters of administration on Jeremiah Parmele’s estate and the request was granted February 14, 1829.62 The document giving him authority to carry on the administration called Griffin a “Friend of Jeremiah Parmele late of the city of New York, deceased.” It also mentioned that Jeremiah had property “which remain unadministered [sic] by Asa Taylor, now also deceased.” There is an extended biographical entry for Griffin that identified him as the son of a farmer, born in the town of Westerlo, Albany County, New York on November 9, 1798.63 When he was eight years old, he was taken to New Town, Fairfield County, Connecticut to live with his uncle, Ebenezer Griffin. He remained there for eight years, attending school. He then returned to his father’s farm, where he remained at home one year, and then commenced working at the blacksmith trade, with a relation. According to the entry, he remained there for only about six months “when he was prompted to seek a wider range for his mechanical operations than that offered in a country blacksmith-shop, and for this purpose went to New York, and apprenticed himself to a Mr. John Johnson, at the black and white smith business.” Since John Parmele came to Wilmington, North Carolina in 1806 from New York, could he have also served an apprenticeship with the “Mr. John Johnson” of New York City, or with someone connected with him?

There is yet another piece of evidence to support the view that the Jeremiah Parmele listed in the Longworth’s 1826-27 New York City directory is the man of that name who married Helen Vail in Connecticut. The land records of Orange County, New York contain three deeds executed in 1833 that relate to Jeremiah.64 They are described as follows: # 47358, Samuel Cornwall, merchant, New York City, granted land in Newburg from the estate of Jeremiah Parmele, Guilford; # 47532, Samuel Cornwall, merchant, New York City, granted land in Cornwall from the estate of Jeremiah Parmele, Guilford; # 48165, Samuel Cornwall, New York City, granted land in Town of Cornwall by Horatio N. Parmele.65 It seems probable that these transactions were carried out as part of the administration of Jeremiah’s estate, especially in light of the legal notices indicating some of his real property would have to be sold to cover debts that he owed in New York City where Samuel Cornwall was a merchant.

As to Helen Parmele, Jeremiah’s widow, she most likely left New York after renouncing the administration of her husband’s estate and returned to her native Connecticut to live with some of her family there. The fact that her name was included in the May 1 and May 3, 1830 issues of the Evening Post of New York among those with letters remaining in the post office of that city may be some evidence that she had already left the city by that date. Helen was living in Connecticut in 1850 when the Federal census was taken for Guilford. It showed Helen Parmele (age 71) living in the household of Lydia Vail (age 83); Helen had a sister named Lydia Vail who died in 1853, so this was possibly her sister. In any case, Helen was living in New Haven when she died. A short notice of her death was carried in the January 27, 1858 issue of the Constitution of Middletown, Connecticut: “DIED. In New Haven, 15th inst., Mrs. Helen Parmelee [sic], relict of the late Jeremiah Parmelee, formerly of Guilford aged 81 years.”

Samuel Parmele, Joseph and Sarah’s youngest son, was born October 19, 1782. If, as is believed, he is the man who advertised in the Wilmington Gazette in November and December, 1806, he would have been twenty-four years old at the time. In the advertisement he stated that he had come to Wilmington from New York, presumably the city of that name. Interestingly, there was a Samuel Parmele in New York City mentioned in a legal notice published in the February 7, 1805 issue of the American Citizen. It referred to him as “an insolvent debtor,” and asked all his creditors to appear before the Recorder of New York City on the Fifteenth of February and show cause, if any, “why an assignment of the said insolvent’s estate should not be made and he discharged according to the direction of an act of the legislature of the State of New York, entitled ‘an act for giving relief in cases of insolvency,’ passed the 2d of April, 1801.” The notice was dated December 26, 1804 and signed by the city’s Recorder. In a subsequent issue of the same newspaper, this one dated May 2, 1806, there is a list of letters left in the post office in that city and it contained the name Samuel Parmele. If this is indeed Samuel Parmele, the brother to Jeremiah, it may be that he left New York either in 1805 or early in 1806, and headed south in hopes of making a new start for himself as a cabinetmaker.

Following Samuel Parmele’s advertisements in the Wilmington Gazette in December, 1806, no further record of his presence there has been located, most probably because he left North Carolina and returned to Connecticut where he married in Branford on July 2, 1807 to Eunice Frisbie.66 Afterward, he and his wife lived in Branford where they had two children, Joseph, born in 1808, who “went away,” and Sarah, who married Jeremiah Russell.67 According to this family history, Samuel drowned in Long Island Sound in 1812.68 There is another gravestone in Branford’s Old Burying Ground, and it is standing adjacent to that of Capt. Joseph Parmele. On it are inscribed two names, John and Samuel, no doubt Joseph’s sons.

John Parmele, Samuel’s older brother, was born January 10, 1772 and died in March of 1812, when he was forty years old.69 On July 2, 1808 he married Hannah Hall and they lived in Branford where they had twin sons, John, Jr., born January 10, 1809, died November 20, 1809, and Joseph, born January 10, 1809, died March 15, 1813.70 Following the death of the elder John Parmele, a legal notice was placed in the April 14, 1812 Connecticut Herald noting that the probate court for the District of Guilford had allowed six months for creditors of the estate of John Parmele “late of Branford, in said district, deceased,” to exhibit their claims for settlement. The administrators named in the notice were Jeremiah Parmele and Samuel Parmele.

Seth and Joseph Vail

It will be recalled that Jeremiah Parmele’s wife, Helen Vail, had a brother named Jonathan Vail, a goldsmith who lived in Guilford. Born October 18, 1762 at Southold, Long Island, New York he married Clarissa Norton, daughter of Timothy Norton and Elizabeth Ward of Guilford.71 The records show that Jonathan spelled the family name as “Vaill,” but “Vail” will continue to be used here, unless otherwise noted. Jonathan and Clarissa had four children: Seth, Timothy, Elizabeth Ward, and William Starr Vail.

Seth was born in June of 1787 and like his uncle Jeremiah Parmele he too was trained as a cabinetmaker. William Ketchum’s American Cabinetmakers: Marked American Furniture, 1640-1940 has an entry for Seth Vaill [sic] of Guilford, Connecticut in which he states that Vail was active as a cabinetmaker from about 1800, until 1810, but Ketchum does not say where he obtained this information.72 It would seem that if Seth was indeed born in 1787, he would have been too young to have been a journeyman in 1800. Perhaps additional research will help clarify this point. As reported by Ketchum, Seth Vail is known for a Federal period cherry chest of drawers which he made and signed. The incised signature, dated 1806, was found on the front of the chest beneath one of the brass pulls. It reads: “MADE by SETH VAILL 1806.” Both a picture of the chest and the incised signature are included in Ketchum’s book.

Around 1810 Seth left Guilford, Connecticut and moved to the island of Bermuda where he continued with the cabinetmaking trade.73 While living there he married Sally Rebecca Walker of Bermuda, and they had two children: Elizabeth Ward Vail, born April 24, 1815 and William Henry Vail, born in 1817.74 Seth died in Bermuda on November 4, 1818. The book Bermuda’s Antique Furniture & Silver has an entry for Vail who lived and worked on the island in its capital city, Hamilton.75 An obituary that ran in the November 7, 1818 issue of the Bermuda Gazette said that he was survived by his wife and two children. The headquarters of the Bermuda National Trust occupies an early plantation house called Waterville, one of the island’s oldest houses and best known landmarks. It was built in the late 1720s and occupied by members of the Trimingham family from the time it was built until 1990, when the last member of the family to live there died. There is a publication by the Trust that discusses the house and its furnishings and it mentions a pair of tea tables of imported West Indian mahogany made for the house around 1811 by Seth Vail; the tables are on display in the drawing room.76 One of the tables was signed by Vail and dated 1812 (Fig. 11, Waterville Samuel Vail tea table, Bermuda National Trust Collection) (Fig. 12, underside of table shown in Fig. 11, inscribed “Made by S. Vaill/1812”, Bermuda National Trust Collection).

Before proceeding to a discussion of Jeremiah Parmele’s connection with Josiah Deming, one other member of the Vail family will be mentioned briefly: Joseph Vail, a cabinet and chair maker who worked in New York City. Ketchum also has an entry for him, but Ethel Bjerkoe has a more detailed one in her book, The Cabinetmakers of America that reads: “First directory of New York City, printed in 1786, does not list Vail. Listed in 1790 as cabinetmaker at 153 Queen St.; from 1791 to 1797 at Bowery Lane; in 1798 at Grand St. In 1799 and 1800 listed as Joseph Veal [sic], chairmaker, on Grand St. In 1802 and 1803, his name is again spelled correctly in directory. In 1804 moved to 54 John St., where he remained until 1806. His label is found in a mahogany slant-top desk—shown in Antiques, February 1944—the label giving 32 Beekman St. as his address. He was probably at this address before the first directory listing.”77 Not much is known about Joseph’s origins, although Nancy Goyne Evans, the author of Windsor-chair making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer, states that, sometime after 1786 he moved from Millbrook in the Hudson River Valley to New York City.78 If so, he may be the Joseph Vail who, described as “Joseph Vail a lad that bound himself an Apprentice” received a certificate of removal the 11th month, 23rd day, 1786 from the Nine Partners Quaker Monthly Meeting in Millbrook to the Monthly Meeting held in New York City.79 Joseph Vail died in September of 1805, according to a list of deaths compiled by the New York City’s Office of the Board of Health and published in the October 1, 1805 Commercial Advertiser of that city. He must have been quite successful as a cabinet and chair maker because the 1805 inventory of his estate included 587 framed Windsor chairs, 75 rush-bottom chairs, and several armchairs and settees.80 On October 29, 1805, his widow, Mariam [sic] Vail, applied for letters of administration on his estate.81 In the document, Joseph is called “late of this City of New York Windsor chair maker.” Whether Joseph Vail is connected with other members of that family discussed here has not been determined, but it seems a possibility.

Parmele & Deming

It was stated earlier that the name Jeremiah Parmele appeared in an advertisement that ran in the Georgetown Gazette of South Carolina on November 13, 20, 27 and December 3, 10, 1799. The notice was for the firm of Parmele & Deming, cabinet and chair makers, and was signed by Jeremiah Parmele and Josiah Deming. No further record of either of these men has been found in South Carolina. It appears Parmele returned to Connecticut. Did Josiah Deming also come from and return to Connecticut?

Research suggests that the Josiah Deming who was Jeremiah Parmele’s partner was the son of Josiah Treat Deming of Guilford, Connecticut, where he was born on August 31, 1775.82 His wife, whom he married on December 11, 1801, was Martha Brown, daughter of Hugh Brown and Olive Sage.83 According to a history of the Deming family of Wethersfield, Connecticut, Josiah was “a cabinet maker, and a builder of [musical] organs,” and lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where all his children were born except for the last two, who were born in Batavia, New York.84

A history of New Haven published in 1887 included an advertisement from the December 8, 1800 issue of the Connecticut Journal that gave notice Josiah had established himself in the cabinet business there: “Josiah Deming informs the public that he is carrying on the cabinet business, opposite the Church, next door south of Scott’s Barber Shop, where any kind of Cabinet Furniture may be made expeditiously, with taste and elegance, all orders punctually attended to, and all favors gratefully acknowledged by the public’s most obedient servant.”85 So far as it goes, the last line in Josiah’s notice is nearly identical to one that ran in the Georgetown Gazette a year earlier: “All orders for work in their way will be punctually attended to and greatfully [sic] acknowledged, by the public’s most obedient servants.”

This same history also mentioned Oliver Deming, noting that he was established in the cabinet business in State Street, between Court and Chapel Streets, even earlier than December 8, 1800 date given for Josiah, and continued there until his death in 1825.86 Oliver was a member of the same Deming line as Josiah, although he was several years older. He was born June 7, 1758 in Wethersfield, the son of Lemuel Deming and Hannah Standish.87 It is believed that that Oliver trained with an unidentified cabinetmaker, most likely Israel Porter (born, 1759) who worked as a journeyman in the Eliphalet Chapin shop in the late 1780s.88 A substantial amount of furniture made and signed by Oliver Deming has been identified and he and the “Oliver Deming Group” are discussed in detail in the book, Connecticut Valley Furniture: Eliphalet Chapin and His Contemporaries, 1750-1800.89 In the 1790s Oliver left Wethersfield and moved to New Haven where he eventually formed a partnership with Josiah, on State Street.

Although Oliver Deming continued in the cabinet business until his death in 1825, Josiah turned his skills toward other endeavors, including the making of artificial limbs, and advertised his inventions in newspapers, far and wide. One notice even ran in the March 15, 1816 Norfolk & Portsmouth Herald, a Virginia newspaper: “An Improvement in Artificial Limbs. Mr. JOSIAH DEMING cabinet maker, New Haven, Connecticut, has invented a new plan for making artificial legs.—He has lately completed one for Mr. Atwater, of that city, who with many others, pronounce it superior to any other now in use . . .”90 Josiah was still making artificial limbs in 1819 when another of his advertisements appeared in the Connecticut Herald: “Invalids Take Notice. The Public are hereby informed that the subscriber is in the practice of making Artificial Spring Legs. All persons who are in need of such, are requested to address a line to him (by mail or otherwise) for further information; and it shall be immediately attended to.” This notice was signed by Josiah and gave an address in New Haven, on Olive Street near the Museum. Not long after this advertisement was published, he and his family left New Haven and moved to Batavia, New York. Soon after his wife’s death there on October 1, 1825, he left New York altogether and moved to Bloomington, Indiana.91 It is said he was a skillful workman, and that he made a wooden clock, by hand, with a knife.92

The Deming family of Wethersfield also produced two other well-known cabinetmakers, brothers Simeon and Barzillai Deming. Simeon was born May 10, 1769 in Wethersfield and died November 23, 1855 in East Bloomfield, New York.93 He moved to New York City in 1793, remaining there in partnership with William Mills until 1798.94 The firm of Mills & Deming was in business on Queen (later Pearl) Street in Manhattan from 1793 until 1798.95 They are, perhaps, best known for a spectacular Federal mahogany sideboard inlaid with swag and tassel decoration, which was made for Gov. Oliver Wolcott of Connecticut.96 It is now in the Kaufman collection on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.97 The sideboard and a mahogany and bird’s eye maple Federal tambour desk in a private collection contain the firm’s label: “Mills & Deming, No. 374 Queen Street, two doors above the Friends Meeting, NEW-YORK Makes and sells all kinds of Cabinet Furniture and Chairs, after the most modern fashions . . . on reasonable terms.”98 In 1813, Simeon Deming left the cabinet business and removed to Bloomfield, New York where he began farming, an occupation he followed for the remainder of his life.99

Simeon’s brother, Barzillai (also spelled Barzilla, and in other variants) was born October 29, 1781 in Wethersfield and married in Hartford on April 21, 1808 to Hannah Wolcott Robbins.100 He must have moved to New York City soon after his marriage, because his oldest child, a daughter named Sarah, was born there on August 26, 1810.101 He is listed as a cabinetmaker in New York City directories as early as 1810. By 1820 he was in partnership with another cabinetmaker, Erastus Bulkley, in a firm called Deming & Bulkley that had a presence in both New York City and Charleston, South Carolina; their New York address was 65 Beekman Street. The firm of Deming & Buckley was active in New York City from 1820 until 1850, with its last appearance being in Doggett’s New York City Directory for 1850-1851.102 An extended discussion of this firm can be found in the monumental three volume work, The Furniture of Charleston, 1680-1820 by Rauschenberg and Bivins.103 It notes that Deming & Bulkley must have had one of the longest-operating partnerships advertising in Charleston.104 Details concerning the operation of this firm in that city will not be repeated here, other than to point out that from 1820 until 1841, they also operated as “cabinet warehousemen,” in Charleston, importing large quantities of New York furniture and other decorative items such as Venetian blinds and gilt cornices into that city. Barzillai Deming remained active as a cabinetmaker in New York City until 1850, but died a few years later on December 20, 1854.105

Conclusion

The research in this article started out as an effort to identify two cabinetmakers named Parmele that made appearances in the South during the period 1799-1808. The results suggest they were brothers who came from, and returned to, Connecticut after their southern ventures; where and by whom they were trained in the cabinet trade has not yet been determined. As research progressed it did more than simply identify them; it also brought to light their linkages through family ties to other Connecticut cabinet and chair making relations, the Vail and Deming families that also had southern ties. Members of the sea-going Vail family (Jeremiah Parmele’s father-in-law, Jonathan Vail, was a sea captain) were involved in the Atlantic coastal trade in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and may well have been involved in transporting northern goods to southern ports, perhaps even cabinet goods made by members of the Parmele family. It is unfortunate that only one piece of furniture that can be attributed to either Jeremiah or Samuel has come to light thus far. Whether other signed pieces will emerge in the future is unknown. They, like so many other talented artisans of that era, labored mostly in obscurity. Hopefully, future researchers will uncover more of their story.

Published on: May 5, 2016

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

Endnotes

1 Unless otherwise indicated, the spelling “Parmele” will be used here, although it appears in the records in numerous variants, including Parmelee, Parmelle, Parmale, Parmalee, Parmly, and other spellings.

2 Bivens, John, Jr. The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700-1820. Winston-Salem, NC: The Museum of Southern Decorative Arts, 1988, p. 491.

3 New Orleans Auction Galleries, July 27-29, 2012, Lot # 1192. Accessed at http://neworleansauction.com/archive/asearchentry.asp?s=1203.

4 Bivins, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 416, 417, 422.

5 This notice comes from a search of the MESDA Craftsman Database, an on-line collection of primary source information on artisans and artists practicing trades in the early South. Accessed at http://www.mesda.org/research_sprite/mesda_craftsman_database.html.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 MESDA Craftsman Database.

10 Colonial Williamsburg collection of furniture of the American South, Acc. No. 1930-120. Accessed at http://emuseum.history.org/view/objects/asitem/search@/11/title-asc?t:state:flow=7ca0a77d-5370-4473-83ad-058f327a605e.

11 Wilmington Furniture, 1720-1860. Wilmington, NC: St. John’s Museum of Art and Historic Wilmington Foundation, 1989, p. 14.

12 Ibid., p. 19.

13 Alexander, Forsyth M. “Cabinet Warehousing in the Southern Atlantic Ports, 1783-1820,” Journal of Southern Decorative Arts, Museum of Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, NC, November, 1989, vol. 15, no. 2.

14 Ibid., p. 3.

15 Ibid., p. 4.

16 Ibid., pp. 4-5.

17 Ibid., p. 21.

18 Ibid., p. 22.

19 Ibid., p. 23.

20 MESDA Craftsman Database.

21 Wilmington Furniture, 1720-1860, p. 17.

22 Connecticut Historical Society, museum and library. Accessed at http://emuseum.chs.org/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search$0040/0/title-asc?t:state:flow=aa901b7d-51bb-4f3c-9e06-65b0455c58dd.

23 Ibid.

24 Skinner auction # 2524B, held November 7, 2010. Accessed at http://www.skinnerinc.com/auctions/252B/lots/173.

25 Muller, Donald, “Everyman’s Time: The Rise and Fall of Connecticut.” Accessed at http://www.ctvisit.com/travelstories/details/everymans-time-the-rise-and-fall-of-connecticut/60.

26 Dean, John Ward, ed. The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Boston, MA: The Society, 1899, vol. 53, p. 407.

27 White, Lorraine Cook, ed. The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Town Vital Records. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1994-2002, vol. 3, pp. 181, 296.

28 Barbour Collection, vol. 3, p. 296.

29 Talcott, Alvan, comp. Families of Early Guilford, Connecticut. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., vol. 2, 1984.

30 Ibid., p. 963.

31 Ibid.

32 Connecticut Probate Court (Guilford District), vol. 18-19, 1783-1820.

33 Capt. Joseph Parmelee gravestone. Accessed at http://www.thefamilyparmelee.com/xt03-0065.html.

34 Connecticut Probate Court (Guilford District), vol. 18-19, 1783-1820.

35 Families of Early Guilford, p. 964.

36 Barbour Collection, vol. 2, p. 183.

37 Mather, Frederic Gregory. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut. Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, Printers, 1913, p. 616.

38 Vail, Henry Hobart. A Genealogy of some of the Vail family descended from Jeremiah Vail at Salem, Mass., 1639. New York, NY: The De Vinne Press, 1902, pp. 50-51.

39 Ibid.

40 Families of Early Guilford, p. 964.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid., p. 974.

43 Ibid.

44 Year:1800; Census Place: Guilford, New Haven, Connecticut; Series: M32; Roll: 2; Page: 63; Image: 169; Family History Library Film: 205619.

45 Year: 1810; Census Place: Guilford, New Haven, Connecticut; Roll: 2; Page: 473; Image: 00486; Family History Library Film: 0281230; Year:1820 Census Place: Guilford, New Haven, Connecticut; Page: 46; NARA Roll: M33_3; Image: 56.

46 Green, Samuel. The Connecticut Register For The Year Of Our Lord, 1808. New London, CT: Printed and sold by Samuel Green, 1808, p. 99.

47 Arnold, Douglas M., ed. The Public Records of the State of Connecticut. Hartford: CT: The Office of State Historian, 1997, p. 20.

48 Green, Samuel. The Connecticut Register For The Year Of Our Lord, 1812. New London, CT: Printed and sold by Samuel Green, 1812, p. 114.

49 Arnold, Douglas M., ed. The Public Records of the State of Connecticut. Hartford CT: The Connecticut State Library, 2012, p. 19.

50 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York, NY: Thomas Longworth, 1826, p. 371.

51 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, June 25, 1823.

52 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1825.

53 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1827, p. 379.

54 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1829, p. 439.

55 Ibid.

56 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1834, p. 535.

57 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1835, p. 510.

58 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY: Thomas Longworth, 1836.

59 Executors Renunciations, 1792-1890, Index, 1830-1912; Author: New York. Surrogate’s Court (New York County); Probate Place: New York, New York, February 18, 1828.

60 Letters of Administration (New York County, New York), 1743-1866; Index, 1743-1910; Author: New York. Surrogate’s Court (New York County); Probate Place: New York, New York, February 18, 1828, p. 19.

61 Longworth, Thomas, ed. Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, And City Directory. New York: NY, 1827, p. 471.

62 Letters of Administration (New York County, New York), 1743-1866; Index, 1743-1910; Author: New York. Surrogate’s Court (New York County); Probate Place: New York, New York, February 18, 1828, p. 60.

63 Bigelow, David. History of Prominent Mercantile and Manufacturing Firms In the United States With A Collection of Truthful Illustrations, Representing Mercantile Buildings, Manufacturing Establishments, And Articles Manufactured. Boston, MA: Published by David Bigelow, 1857, vol. 6, p. 261.

64 Rootsweb post, Subject: Cornell & Knapp Deeds in Orange Co. Posted January 7, 2000 by Tom Cornell. Accessed at http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/NYORANGE/2000-01/0947304024.

65 Cornwall is a town in Orange County, New York, located about fifty miles north of New York City on the banks of the Hudson River.

66 Families of Early Guilford, p. 964.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Barbour Collection, vol. 3, p. 392.

70 Families of Early Guilford, p. 963.

71 A Genealogy of some of the Vail family descended from Jeremiah Vail at Salem, Mass., 1639, pp. 89-90.

72 Ketchum, William C. Jr. American Cabinetmakers: Marked American Furniture, 1640-1940. New York, NY: Crown Publishers, p. 352.

73 A Genealogy of some of the Vail family descended from Jeremiah Vail at Salem, Mass., 1639, p. 150.

74 Ibid.

75 Hyde, Bryden Bordley. Bermuda Antique Furniture & Silver. Hamilton, Bermuda: Bermuda National Trust, 1971, p. 28.

76 “Waterville: Historic House & Gardens, Teachers Resource Guide,” Hamilton, Bermuda: Bermuda National Trust, p. 17. Accessed at http://www.moed.bm/Documents/Waterville%20Historic%20House%20and%20Gardens.pdf.

77 Bjerkoe, Ethel Hall. The Cabinetmakers of America. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1957, p. 223.

78 Evans, Nancy Goyne. Windsor-chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2006, p. 288.

79 Ancestry.com. Dutchess County, New York Quaker Records [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA. Original data: Cox, John, Jr., comp. Quaker Records: Nine-Partners Monthly Meeting, Dutchess Co., N.Y.

80 Windsor-chair Making in America: From Craft Shop to Consumer, p. 206.

81 Letters of Administration (New York County, New York), 1743-1866; Index, 1743-1910; Author: New York. Surrogate’s Court (New York County); Probate Place: New York, New York, p. 140.

82 Deming, Judson Keith. Genealogy of the Descendants of John Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut, With Historical Notes. Dubuque, IA: Mathis-Mets Co., 1904, p. 206.

83 Ibid.

84 Ibid.

85 Atwater, Edward E., ed. History Of The City Of New Haven To The Present Time. New York, NY: W. W. Munsell & Co., 1887, p. 587.

86 Ibid.

87 Genealogy of the Descendants of John Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut, p. 126.

88 Sotheby auction # N08950 held in New York City, January 25, 2013. The catalog description of a cherry Chippendale chest of drawers made by Oliver Deming includes the information about Israel Porter. Accessed at http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.315.html/2012/americana-vo-n08950.

89 Kugelman, Thomas P., Alice K. Kugelman, and Robert Lionetti. Connecticut Valley Furniture: Eliphalet Chapin and His Contemporaries, 1750-1800. Hartford, CT: Connecticut Historical Society, 2005, pp. 382-385.

90 MESDA Craftsman Database.

91 Genealogy of the Descendants of John Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut, p. 206.

92 Ibid.

93 Ibid., pp. 115-116.

94 American Cabinetmakers: Marked American Furniture, 1640-1940, p. 96.

95 Ibid., p. 237.

96 Ibid.

97 Kaufman collection, National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Accessed at http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/press/exh/3564.html.

98 Ibid.

99 Genealogy of the Descendants of John Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut, p. 116.

100 Ibid.

101 Ibid.

102 Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover, and John K. Howat. Art and the empire city: New York, 1825-1861. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000, p. 292.

103 Rauschenberg, Bradford L., and John Bivins, Jr. The Furniture of Charleston, 1680-1820. Winston-Salem, NC: Old Salem Inc.: Museum of Southern Decorative Arts, 2003, vol. 3, pp. 971-975.

104 Ibid., p. 971.

105 Genealogy of the Descendants of John Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut, p. 116.