Research Notes Compiled By Michael L. Marshall

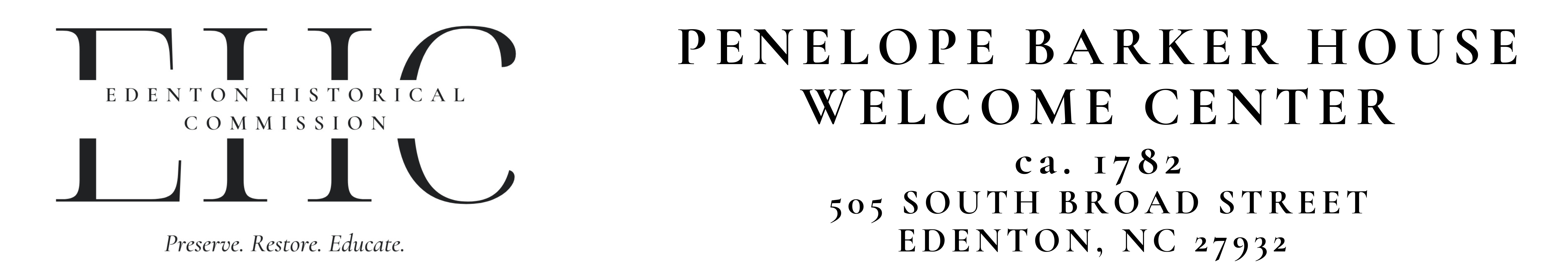

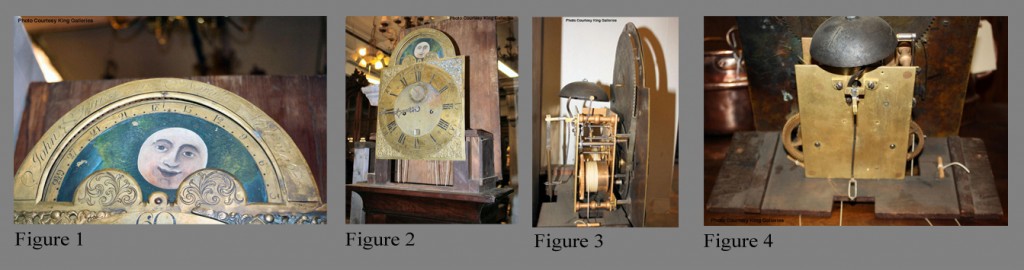

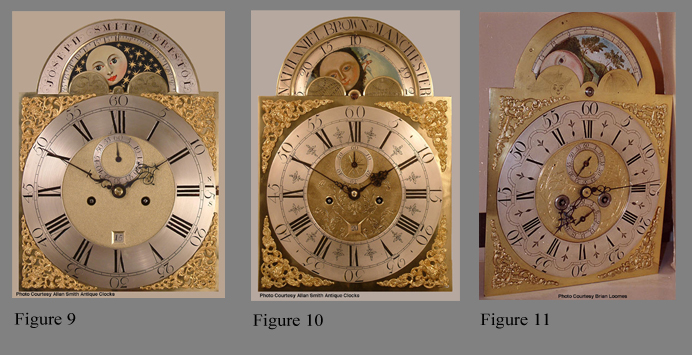

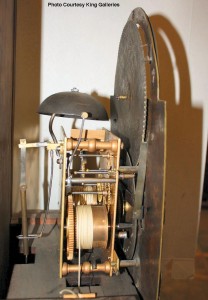

On April 21, 2013, King Galleries, ofRoswell, Georgia, auctioned Lot # 114a, described as a “nineteenth-century tall clock in mahogany case with brass dial and moon phases.” The dial is marked “John Jones in Norfolk Virginia,” in the arch over the moon-phase disc (Fig. 1, Signed arch). Other views of the clock are (Fig. 2, Dial and movement mounted in case), (Fig. 3, Side view of movement), (Fig. 4, Back plate of movement), (Fig. 5, Overall view of clock), (Fig. 6, Scrolled-arched pediment of hood), (Fig. 7, Frontal view of waist), and (Fig. 8, Yellow pine backboard of case). The clock sold for a hammer price of $13,000.00, which did not include the 18% buyers’ premium.

A condition report provided by the auction house included the following notes: the clock was in good working order at the time of the sale; the case is mahogany with pine secondary wood; the waist door had been refinished or replaced since the hinges and locks are replacements; the seat board had been repaired, but the bottom board was present and intact. The overall dimensions of the case were given as 102 in. in height, 24 in. in width, and 11 ½ in. in depth.

There was no provenance for the clock other than the fact that it had been consigned as part of a North Georgia estate and that its owner had purchased it about two years earlier at a sale conducted by Jeff Dobson & Associates, Inc., located in Jasper, Georgia. Reportedly, the clock had been consigned to Dobson by a Tennessee family who had owned it for several generations.

The clock’s moon-phase disc has features in common with other examples, both British and American, dating from the 1740s through the 1770s. See, for example, the British dials (Fig. 9, Joseph Smith, Bristol, England, c. 1770), (Fig. 10, Nathaniel Brown, Manchester, England, c. 1750), and (Fig. 11, John Watson, Kirbymoorside, England, c. 1760).

In their book, Southern Furniture, 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, Ron Hurst and Jonathan Prown note that few Americans owned clocks during the seventeenth century but that by the mid-eighteenth century, clock ownership was on the rise.[1] In support of this claim, they point to probate research by Betty Crowe Leviner that indicated that about one in four gentry households in eastern Virginia owned a clock in the period 1750-1770.

The growing presence of clock- and watchmakers in the more urban areas of the South, particularly in Norfolk, Williamsburg, and Fredericksburg, in Virginia, and Charleston, in South Carolina, helped drive this change. Nevertheless, there were far fewer clockmakers in the southern colonies than in the mid-Atlantic or northern regions of the country during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Undoubtedly, many of them spent more time cleaning and repairing timepieces—included those imported from abroad—than in making clocks. As a result, far fewer early clocks made in the South have survived, and this makes clocks, such as the one under discussion here, a rarity.

It is true that many American clockmakers often used a combination of imported and locallymade parts. Insome cases, entire movements were imported. Even so, evidence suggests that there were sufficient numbers of capable clockmakers and engravers in southern cities, such as those mentioned earlier, to produce, not only clock movements, but dials engraved to a high standard, as well.

In an effort to learn more about the John Jones clock, the author requested opinions from Allan Smith and Jim Melchor.[2] Smith is a well-known British clock expert and antiquarian horologist, while Melchor is a southern furniture scholar.

Going only on the basis of photographs provided by King Galleries, Smith ventured that the complete dial, made circa 1750, had been ordered and sourced from Britain but that the rest of the movement had been made in America. His view regarding the dial was based on its quality of engraving, which he characterized as “of a very high order” and “executed by a craftsman engraver.” His opinion was bolstered by his belief that there were probably “precious few” craftsmen of such ability in Virginia at the time it was executed and that “there would have been considerable reciprocal trading between Britain and America in the mid-eighteenth century”.

Smith did note an anomaly with the complete dial. “Look at the dialfoot – bottom left hand side, as viewed from the front. You will notice that it locates in a brass strap ‘extension’ to the frontplate.” That is to say, the dial was attached to, or supported on the front plate in a manner inconsistent with what he considered British work (see Fig. 2). Smith’s opinion that the movement had been made locally in Virginia was based on several observations. He noted “the color of the brass was very ‘orange’ compared to British-made clock brass.” Additionally, he pointed out that the winding barrels of the Jones clock movement had no grooves to guide the gutlines and that, while some British work is also done that way, it is “much the exception.”

Overall, Smith believed that the Jones clock movement “has had a hard life.” As proof, he offered that the lozenge hour and minute hands were of late-eighteenth century painted-dial style, the second hand was an “amateur-made” replacement (see Fig. 2), and that amateur work “is also noted in the soldered rack-tail assembly, soldered back cock, and repairs to the crutch (see Figs. 3 & 4).” Not only that, he observed that the bell hammer was a poor replacement (see Fig. 4). Further, the three “spare holes on the back view of the dial (see Fig. 4 at top of photo and to left of disc) would have been for the moon-phase disc jumper spring which has been replaced by a very delicate addition to the top rear of the arch (see Fig. 3 at top of arch).” Finally, he thought “packing pieces under the seat board for the movement could indicate that the movement has been re-cased (see Fig. 2).”

Melchor, on the other hand, believes that there were clockmakers and engravers in Virginia and elsewhere at the time the clock was made who could have produced a dial of the quality exhibited by the John Jones clock. Based on the photos available, Smith’s assessment, which was provided to him, and his own personal experience and expertise, he proffered the following comments:

“The dial, frontplate, and spandrels were likely Norfolk made but possibly could be all or part British. The odd, non-British attachment of the dial to the frontplate is the key for me here in thinking local production. The urn spandrels are British in flavor (see Fig. 2); however, Norfolk was a very British city with a large contingent of English, Scottish, and Irish trades people supplying locally made ‘British’ goods in the latest tastes.”

“The engraving was done by Jones. He was a capable clockmaker certainly with the ability to do fine engraving. Local gunsmiths and silversmiths also were capable of and, indeed, performed fine engraving. If a British source were providing Jones with read-to-go, pre-engraved clock faces, you would expect to see a number of them surviving with his name, not just one up as we have with this clock.”

“The works were Norfolk made by Jones, though heavily repaired through time. They just look American. While the works are not the most refined as you would expect in a fine British clock with a similar high-end face, they did the job. Unfortunate as the repairs are, they seem honest to keep the clock running for over 200 years. Such repairs are a turnoff for British collectors, but there are far more signed British clocks than signed southern American clocks from which to choose.”

John Jones and Family Connections

In fact, there was a clockmaker named John Jones who worked in the Norfolk, Virginia, area in the eighteenth century, according to the monumental work by Catherine Hollan titled Virginia Silversmiths, Jewelers, Watch- and Clockmakers, 1607-1860: Their Lives and Marks.[3] The following, quoted from her book, discusses Jones:

“John Jones of Norfolk mended a watch belonging to Duncan McNeil but had not been paid before McNeil died. Jones was paid £ 1.1.9 from McNeil’s estate in 1752. In the same year, Lewis Conner wrote his will, bequeathing “my clock now lying in the hands of Mr. Jones in Norfolk Town” to his son Lewis Jr. It may have been this clockmaker John Jones who with Samuel Boush, Jr. on 31 October 1743 witnessed the marriage bond of Roderick Conner and Margaret Scott. Clock making and watch repair seem to have been Jones’ primary business, as indicated by his notice in the Virginia Gazette of 12 December 1755 declaring he would no longer take credit and expected immediate payment: “John Jones . . . great sufferer by time, expenses and endeavoring to get payment, beg no gentleman employ me that will not suit to pay when work is finished or take it ill if I do not deliver their watches till paid; several good eight day and other clocks by me that I would sell cheap for ready money (Ed. Note – This is an extremely important point in establishing Jones made clocks); as I shall work for ready money only, shall make 10% abatement on old prices.”

“He also performed general metalsmithing and silversmithing activities. In 1753 Jones was paid £ 8.16 for repairing the municipal fire engine, ajob generally performed by a silversmith. Nicholas Poole was paid an annual salary of £ 12 or £ 10 from 1764 to 1772 for keeping the fire engine in order, and Samuel Blews took over the responsibility in 1774. Silversmith James Murphree and William Braman (or Bruman), who may also have been a journeyman silversmith or clockmaker, lived in Jones’ Norfolk household in 1752, suggesting he was also performing silversmithing functions at this time.” (Ed. Note – Engraving was part of a silversmith’s trade.)

“John Jones was listed in the tithables counts living in Norfolk borough in the division from the north side of Tanner Creek as far as Spratts (later called Great) Bridge from 1751 to 1754, then on the south side of Tanner Creek to the bridge from 1757 to 1759. He was counted alone in 1751, but in 1752 had with him silversmiths, James Murphree and William Braman (or Bruman). Murphree moved on by 1754 and Braman left by 1757. In spite of his claims to have suffered greatly by crediting people, his personal holdings increased in these years. John Jones was taxed for several Negroes—Sue and Prisilla (1754), plus Ned, Duke, and Fanny (1757), then reduced to three Negroes in 1759—Dick (Duke?), Purela (Prisilla?), and Fanny.”

“He seems to have moved to Suffolk, Nansemond County, in the early 1760s and emphasized silversmithing as his occupation. On 2 April 1762 as John Jones, silversmith of Suffolk, Nansemond County, he sold to the Norfolk merchant Matthew Rothery lot # 56 in Portsmouth at the intersection of County and Middle streets. A second deed was filed on 11 April 1764 and named Jones’ wife Pheleshea, whom he may have married about that time. The vestry of Upper Parish of Nansemond County paid £ 1.6 in 1764 for “cleaning and taking out bruises from Communion Plate and mending organ pipes.” Accounts of administrator Colonel Edward Hack Mosely, Sr. on the estate of Walter Lyon included a payment to “Jno. Jones” of Nansemond for £ 4.14.8 in October 1768, whether for services before 1758 when Lyon died, or after, is not specified. Other references to John Jones owning property in Upper Parish of Nansemond County indicate that he owned land and was present at the processioning by the parish vestrymen from 1747 through 1764 and again in 1775. Whether these are the same men, or related is unclear; however, titles are never found to distinguish local men of the same name as was frequently done.”

“In the 1770s Jones seems to have returned to Norfolk again. He was listed in the tithables for 1771, heading a household of three men—himself, William Jones, and William Bathgate, the young watchmaker. His property was destroyed in 1776 when the British approached the seaport during the Revolutionary War and the town was set on fire to avoid capture. John Jones, goldsmith, was listed among the claimants for repayment for loss of property. This was the last record of the clockmaker-silversmith.”

“One intriguing record may relate to the silversmith. Records of Suffolk Parish in Nansemond County contain a payment to Dr. James Wright for amputating the legs of a John Jones on 16 November 1766. If this is the silversmith, we might expect that his activities would be limited in making necessary house calls to mend organ pipes, and fire engines, regulate clocks, and possibly in working at his workbench. As a shop owner in Norfolk, he would have hired journeymen to do his work as we see he hired Bathgate and perhaps William Jones. The war and destruction of Norfolk can understandably have permanently closed that business.”

This John Jones also appears in other records in this same area. Fillmore Norfleet, in his book Bible Records of Suffolk and Nansemond County, Virginia, Together with Other Statistical Data mentions Jones in his discussion of the early years of the town of Suffolk, in Nansemond County—the town was established in 1742 “at Constance’s warehouse.”[4] According to Norfleet, individuals residing in Suffolk in 1767 included “Lemuel Riddick’s second wife,Esther Robins (whose first husband had been Theophilus Pugh), whom he married May 5, 1761,” and “John Jones and his wife Philishia, a daughter of Col. Daniel Pugh’s granddaughter), who advertised for sale in the Virginia Gazette (May 7th) ‘a new ship . . . burthen about 350 hogsheads of tobacco . . . lying at Suffolk wharf.”’

According to a record found in “Nansemond County, Virginia, deeds conveying land in the upper parish,” contributed by Fillmore Norfleet and published in The Virginia Genealogist, John Jones and his wife, Philisha[5] [Pugh], of the town of Suffolk conveyed to Moses Riddick Sr., of Nansemond County, for £ 8, a plantation of 112 acres.[6] The tract was described as beginning “at the Middle Trudge Path” to a patent line by one Humphrey Griffin, the land being “Part of a Parcel of land Patented by one Humphrey Griffin” February 24, 1717, “and by him sold to Walter Price by deed Bearing Date 26th July 1736, Which said Price sold the Land hereby conveyed unto his Nephew Joseph Price Part of the Pattent aforesaid by Deed . . . Proved in Nansemond County Court which said Joseph Price sold the said Land to Samuel Riddick by Deed Dated 13th August 1750, who soon after departed this life, having just made his will to his wife Ruth Riddick, who also soon after died testate & gave the said piece of land to her Brother John Giles, this said John Giles sold the same land by deed bearing date 13th day of April 1762 to John Jones party to these presents.” The deed was signed by Jones and his wife Pheleshea and recorded at a court held August 10, 1767. It was witnessed by Lemuel Riddick, clerk of the court.

There is further mention of John Jones and his wife in the deed records of Gates County, North Carolina. Gates was formed in 1779 from Chowan, Hereford, and Perquimans counties, and was originally part of an area referred to as the Albemarle. This area was later dividedinto the three previously mentioned counties. However, most of the land within the Albemarle was originally considered part of Nansemond County, Virginia, until 1728 when William Byrd surveyed the “dividing line” between Virginia and North Carolina. In any event, in a deed dated July 1776, John Jones and his wife Phelishia, of Nansemond, Colony of Virginia, conveyed to John Webb of the town of Halifax, Province of North Carolina, for £ 500, a parcel of land on the northeast side of Bennett’s Creek in Chowan County. The land had come into Phelishia’s possession in the division of the estate of Daniel Pugh and adjoined another tract “whereon Ann Gibson now liveth.”[7] The deed was signed by Jones and his wife.

There is another Gates County deed, this one dated November 22, 1779, by which Ann Gibson of Gates County, formerly Chowan, conveyed to her son, John Webb of Halifax County, land located on the northeast side of Bennett’s Creek, which she had also received from the division of Daniel Pugh’s estate.[8]

It seems likely that the Col. Daniel Pugh, whose daughter married John Jones, was the son of Daniel Pugh Sr., who left a Nansemond County will, dated March 25, 1700. In this will, Pugh left 250 acres adjacent to Cross Swamp to his grandson, John Duke, “being the son & heir” of his daughter Ann [Pugh]. In fact, Daniel Pugh Sr. appears in several land records transcribed in Volumes I and II of the series, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants by Nell Nugent.[9] For example, Patent Book No. 8 records that on April 21, 1695, Mr. Daniell [sic] Pugh received a patent for 1,134 acres in the upper parish of Nansemond County, called “Dogwood Neck,” on the west side of Bennett’s Creek for importing twenty-three headrights including one David Jones (no known connection to John Jones). Patent Book 9 mentions that on October 25, 1695, Pugh received another patent, this one for 99 acres, in the upper parish of Nansemond. Daniel Pugh Sr. received other patents as well, including one for 415 acres on April 26, 1698 in the upper parish of Nansemond called “Walnutt Neck,” on the east side of Bennett’s Creek (Patent Book 9, page 155). Other patents to Daniel Pugh Sr. included 24 acres on October 15, 1698 in Nansemond (Patent Book 9, page 182); 55 acres on October 26, 1699 in the upper parish of Nansemond (Patent Book 9, page 229); and 422 acres in the upper parish of Nansemond on November 7, 1700 adjacent to his “Dogwood Neck” tract (Patent Book 9, page 272). There is another patent (Patent Book 9, page 303), this one to Nicholas Stallings and dated April 25, 1701, for 63 acres in the upper parish of Nansemond at a place called the “White Marsh” for transporting two persons—the record says “Daniel Pugh, twice imported.”

By his wife Ann, Daniel Pugh Sr. had a daughter, Ann, who married John Duke, as well as sons John, Francis, Theophilus, and Daniel Pugh Jr. The latter is likely the “Col. Daniel” who was the father of Pheleshia (Pugh) Jones.

Daniel Pugh Jr. (Col. Daniel) died intestate leaving 450 acres of land, which he had inherited from his father, to his son, Daniel Pugh III. This land was part of a patent for 750 acres granted on October 10, 1670 to Col. Thomas Dew, which is today located in the city of Suffolk, Virginia.

Daniel Pugh III devised this same 450 acres to be divided among his mother and three sisters, one of whom was likely Phelishia Pugh who married John Jones, and the other, Ann Pugh, who married John Duke. It is believed that John, James, and Daniel Duke were sons of this John Duke of Nansemond and his wife, Ann (Pugh) Duke.

There is a deed of November 22, 1739, by which John Duke of Nansemond County sold to Richard Newsum, 250 acres of land adjoining Cross Swamp on Richard Newsum’s land, “which my grandfather, Daniel Pugh, bought of James Peters and gave to me being the son and heir of Ann [Pugh] according to his will made March 25, 1700.”[10]

The will of Francis Pugh, son of Daniel Sr., is abstracted in Grimes.[11] It is dated July 5, 1733 and proved October 4, 1736. In it, he leaves to his son John the “plantation whereon I now live,” and to his son Thomas, land “at the Emperors Field which I bought of Christian Hitteburgh.” He also directs that his lands in Bertie and Edgecombe Precincts be divided between his two sons, and that his lands in Virginia be sold. His Negroes were to be divided between his wife and children. The instrument also states that “It is my will that my wife have the management of the ferry where Henry Horne lives . . .” In his will, Pugh ordered his executors and trustees to pay “pay all my Just and true Debts, which I am Indebted to any person whatsoever and the overplus [surplus] to be Laid out in Young Negroes, and be Equally Divided amongst all my Children and likewise all my Merchantizeing Goods I Desire they may be Sold and the Effects that Comes for it to be Laid out in Young Negroes and to Remain with my Wife Dureing the time she Lives a widow and afterwards to be Equally Divided amongst all my Children.” He appointed his wife, Pherebee, executrix. Francis’ wife was Pherebee, or Pheribe, Savage of Virginia. She married, secondly, Thomas Barker Esq., of Bertie, but afterwards of Edenton, North Carolina.[12]

The will of John Pugh is also abstracted in Grimes. It is dated April 14, 1740, and proved August 4, 1740. It mentions his wife, Hannah, son, John, and his two brothers (named executors), Theophilus and Daniel Pugh. In his will, John also bequeaths all his land in both Virginia and North Carolina to his two brothers in trust for son, John.

According to the book, Adventurers of Purse and Person,Theophilus Pugh, son of Daniel Sr., married Esther Robins of Northampton County, Virginia, daughter of John Robins—the marriage bond is dated February 9, 1738/39.[13] She was born November 10, 1722 and died September 23, 1775. Theophilus Pugh died November 1, 1745 and his widow, Esther, married, secondly, Col. Lemuel Riddick of Nansemond County.

A “WH Cabinetmaker” Connection

As noted earlier, Francis Pugh, son of Daniel Sr., married Pheribe Savage of Virginia. His will listedsons, John and Thomas, but there was also another child “in esse.” Research indicates that this posthumous child was another son, Francis Pugh, who married Mary Whitmell.

Thomas Pugh, son of Francis and Pheribe, who was born in Nansemond County, married Mary Scott. Their children included son, William Scott Pugh, who married Winifred Hill, whose will was proved in February 1809. Their children included Augustin Pugh, William Hill Pugh, and William Alston Pugh.

William Alston Pugh (born 1776, died 1836) is mentioned in the book by Newbern and Melchor, W H Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Solved, in connection with a house built by William Seay, the “W H Cabinetmaker,” still standing in Bertie County, North Carolina.[14] The following passage comes from this book:

“The third example of Seay’s pedimented front-door surround is encountered on the Pugh House, located across the road from Woodville. This house was built around 1812 and represents the last known house to have been built by Seay. Whitmell Hill Pugh and William Alston Pugh were the children of William Scott Pugh and his wife, Winifred Hill, the sister of Whitmell Hill. William Scott Pugh’s father was Lt. Col. Thomas Pugh, a native of Nansemond County. Thomas moved to Bertie County and lived at Quirocky in the Indian Woods section of the county, east of Woodville. On March 11, 1806, Whitmell Hill Pugh married Mary Hill of Woodville, the widow of Pugh’s first cousin, John Hill Pugh. After their marriage, Whitmell and Mary remained at Woodville. On January 1, 1812, Whitmell Pugh transferred, by deed of gift, 18 acres across the road from Woodville to his brother, William Alston Pugh. Soon thereafter, the Pugh House was built by Seay for William Alston Pugh.”

In conclusion, it seems that the John Jones whose name appears on the Norfolk, Virginia, clock married into a prominent Nansemond County family, a family that later had connections to the well known cabinetmaker referred to as the “W H Cabinetmaker.” Newbern and Melchor, in their well-researched and documented book, make it clear that this cabinetmaker was, in fact, William Seay, who built many of his best-known pieces of furniture for Whitmell Hill (born February 12, 1742, died September 26, 1797). Hill, a prominent planter from Martin County, North Carolina, was a delegate for North Carolina to the Continental Congress from 1778 until 1780.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

Published on: May 16, 2014

[1] Hurst, Ronald L., and Jonathan Prown. Southern Furniture, 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection. Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in Association with Harry N. Abrams, 1997.

[2] Personal communication, Allan Smith, April 19 and April 20, 2014; Personal communication, Jim Melchor, April 20, 2014.

[3] Hollan, Catherine B. Virginia Silversmiths, Jewelers, Watch- and Clockmakers, 1607-1860: Their Lives and Marks. [McLean, Va.]: Hollan, 2010.

[4] Norfleet, Fillmore. Bible Records of Suffolk and Nansemond County, Virginia, Together with Other Statistical Data. [S.l.]: Author, 1963.

[5] This name appears in several variants in the records and is recorded in this research note as it appears in them.

[6] Norfleet, Fillmore. “Nansemond County, Virginia, deeds conveying land in the upper parish.” The Virginia Genealogist, Vol. 11, no. 3 (July/Sept. 1967)-Vol. 11, no. 4 (Oct/Dec. 1967).

[7] Taylor, Mona Armstrong. Gates County, North Carolina Deeds, Book A-5, 1776-1803. Harker Heights, TX: M.A. Taylor, 1987.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Nugent, Nell Marion. Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants. Richmond: Virginia State Library, Vol. I (1977), Vol. II (1979).

[10] A Guide to the Riddick Family Papers, 1720-1856, Virginia State Library, cited in “DUKE Families of Nansemond County, Virginia; before 1750,” by Fred Duke, copyright 2002 by Tony Cox. Retrieved from http://genealogy.ztlcox.com/~xcc2all/cfreddukefiles/c_fred_duke_files_before1750.htm.

[11] Grimes, J. Bryan. Abstracts of North Carolina Wills Compiled from Original and Recorded Wills in the Office of the Secretary of State. Raleigh, NC: E.M. Uzzell & Co., Printers and Binders, 1910.

[12] Hathaway, J.R.B., ed. and financial agent. The North Carolina Historical and Genealogical Register, Vol. I, No. I, January 1900.

[13] Meyer, Virginia M., and John Frederick Dorman. Adventurers of Purse and Person: Virginia 1607-1624/5. Third Edition 1987. The Dietz Press, Inc., Richmond, Virginia).

[14] Newbern, Thomas R.J. and James R. Melchor. W H Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Solved. Benton, KY, Legacy Ink Publishing, 2009.