The story of French swords imported for the Virginia Militia during the American Revolution and their long and distinguished service in post-Revolutionary Virginia.

By Giles Cromwell

Dedicated to Baylor Cromwell, my father, whose early collecting was an inspiration to me.

Editor’s Note: Giles Cromwell is the leading authority on the procurement of French swords for Virginia during the Revolutionary War. Here, Cromwell has revised and updated his 1995, privately published treatise on the subject. Cromwell is also the author of The Virginia Manufactory of Arms, the comprehensive study published by the University Press of Virginia in 1975. This book remains the primary source for information on those weapons produced in Richmond, VA during the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

To enlarge the figures in the body of this article, simply click on them once. To close the enlargement, click on the X in the top right corner. For even higher resolution enlargements for each figure, go to the photo gallery at the end of the article and click once on the desired figure.

In an effort to procure arms and supplies for Virginia during the American Revolution, Governor Patrick Henry, with the advice of Council, appointed William Lee in December of 1777 as the state’s first commercial agent in France. This appointment would give the state an important and direct presence in the European market. Except for infrequent private negotiations with individuals abroad, the America colonies before the Revolution had to conduct commercial relations with foreign governments through English agents, who placed the interests of England first. Consequently, no precedent existed for direct colonial foreign trade or diplomacy.

William Lee, however, who had been residing in France for some time, had established preliminary contacts through an earlier appointment by Congress as a commercial agent, along with Thomas Morris, for the United States. Soon after his new appointment by Governor Henry, William empowered his brother, Arthur, to assist him. Arthur also had previous foreign connections, having been appointed by Congress in 1776 to act as the third member of a new diplomatic commission in Paris. His Paris residence and liaison with French and German officials would facilitate the securing of French assistance for Virginia.

Paralleling William and Arthur’s new service on the state’s behalf, however, was a third independently sanctioned individual with equally strong French connections, Jacques LeMaire. The son of a prominent French family, LeMaire had come to Virginia with the permission of the French court in 1777 in search of a political future in America. Governor Henry quickly accepted his offer of assistance, provided him with a list of needed materials for the state, and commissioned him with the rank of captain. LeMaire also received important invoices for war materiel from Mr. Loyeante, Virginia’s inspector general of artillery and military stores. LeMaire’s potential service to the state was strengthened further by a letter of introduction to the Honorable Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was soon to receive appointment as America’s first minister to France in 1778. Before leaving Virginia, Governor Henry instructed LeMaire to contact the Lees upon his arrival in France.

Both William and Arthur resented LeMaire’s intrusion into their role as state agents. When LeMaire arrived in late spring of 1778, William had left Paris for business at the court of Vienna, where he was seeking cannon and ordnance for the state. In his brother’s absence, and with little regard for LeMarie’s appearance in Paris, Arthur gave him traveling funds and directed him to go to Strasbourg and other principalities, …”to engage the sabers, etc. for the light horse.” 1 Arthur believed this arrangement would keep LeMaire occupied and removed from their affairs. In the absence of funds, and because no line of credit had been established officially between Virginia and France, and with little negotiating leverage based on the pledging of Virginia tobacco, he considered the young Frenchman’s task to be futile. However, the Lees had underestimated LeMaire. He possessed impressive credentials not only from within his own country, but also from Virginia. He would be dealing with his peers, and the question of payment would be answered by the agents’ acceptance of credit based on LeMaire’s promise to pay. The desire of the sword manufacturers to secure a potentially lucrative arms contract looked promising. Consequently, successful negotiations were well within his grasp when LeMaire wrote William on 11 June 1778 and included prices for swords and other articles. 2 Upon receiving LeMaire’s letter, William wrote him from Vienna on 27 June that the prices were too expensive and the cost of transporting the articles from an area so remote from a seaport would be prohibitive. He concluded, “I will only observe that the Bayonets must be found where the fusils are bo’t and the time will not allow for our waiting ‘till the sabers are made, we must find them ready made to be transported immediately to the place of their destination.” 3 Either LeMarie did not receive this letter or he purposely disregarded it, because on 4 July 1778 he entered into a contract with the agents at Strasbourg for swords, pickaxes, hatchets, and shovels.

The news of LeMaire’s “success” reached William by 14 July, and the latter wrote an angry letter to Arthur commenting, “I know not what particular motive Captain LeMaire has in determining at all events to lay in several articles at Strasbourg.” “Guess you at my surprise to find his letter saying he had made a contract on the 4th instant for some of the very articles even at a higher price than the manufacturer’s first price and the charges of carriage from the manufacturer to the city of Strasbourg only exactly the same is usual and commonly paid for land carriage.” “He has also favored me with two folio sheets of reasons written by the manufacturer why we should buy everything that is wanting at Strasbourg which is the most compleat rhapsody of nonsense I ever read.” 4

The Lees considered LeMaire’s action reprehensible, and although their resentment of him continued, nevertheless, they wisely did not attempt to void his arrangements in Strasbourg. On 30 July 1778, William authorized Arthur to provide the necessary invoices and documentation for those supplies, which would total some 40,000 livres.

The swords that Virginia eventually received were special order weapons manufactured in Klingenthal, located southwest of Strasbourg. France had obtained most of its sword blades from Germany until some Solingen craftsmen were encouraged to open a manufacturing site at Klingenthal in France’s Alsace region about 1729. 5

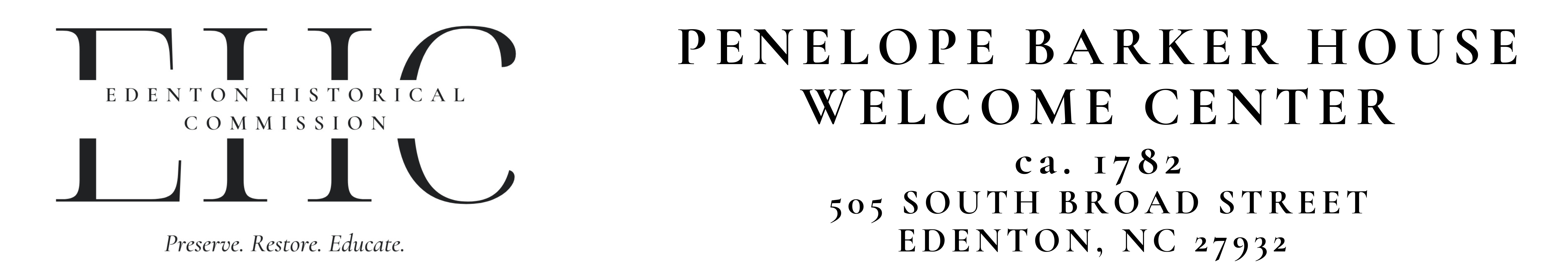

There were two different styles of swords in LeMaire’s Klingenthal contract that would conform generally to the standard French Model 1767 hanger or short sword. They had a two-piece brass hilt consisting of a ribbed handle with a large capstan at the pommel and a stirrup-shaped guard. The hilt averaged approximately 5 ¼ inches in length. The blades of the swords for Virginia, however, deviated somewhat from the regular French hanger-style weapon. These particular swords of the LeMaire contract had a slightly curved flat blade with a wider blade section or false edge running approximately eight inches to the point or tip. The blade lengths varied from approximately 23 ¾ inches to 26 ½ inches, depending of the style of sword (Fig. 1, Comparison of the two hanger-styles of French contract swords for Virginia – grenadier sword on left and artillery sword on right. Note blade lengths and profiles).

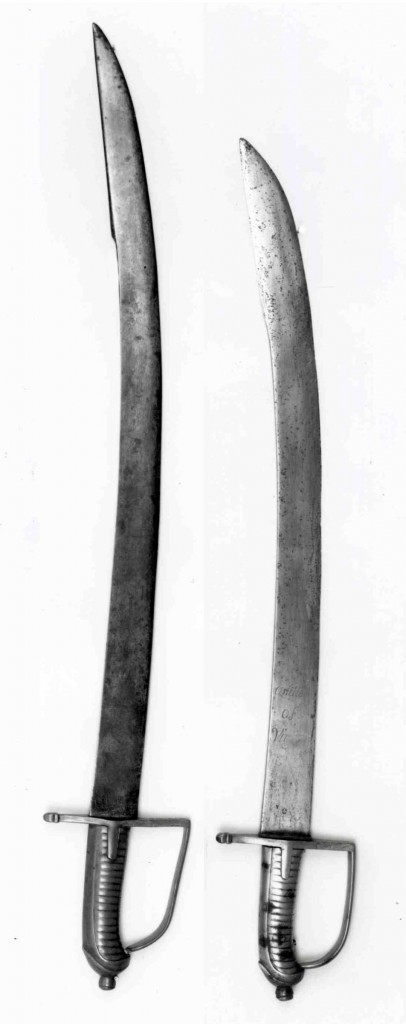

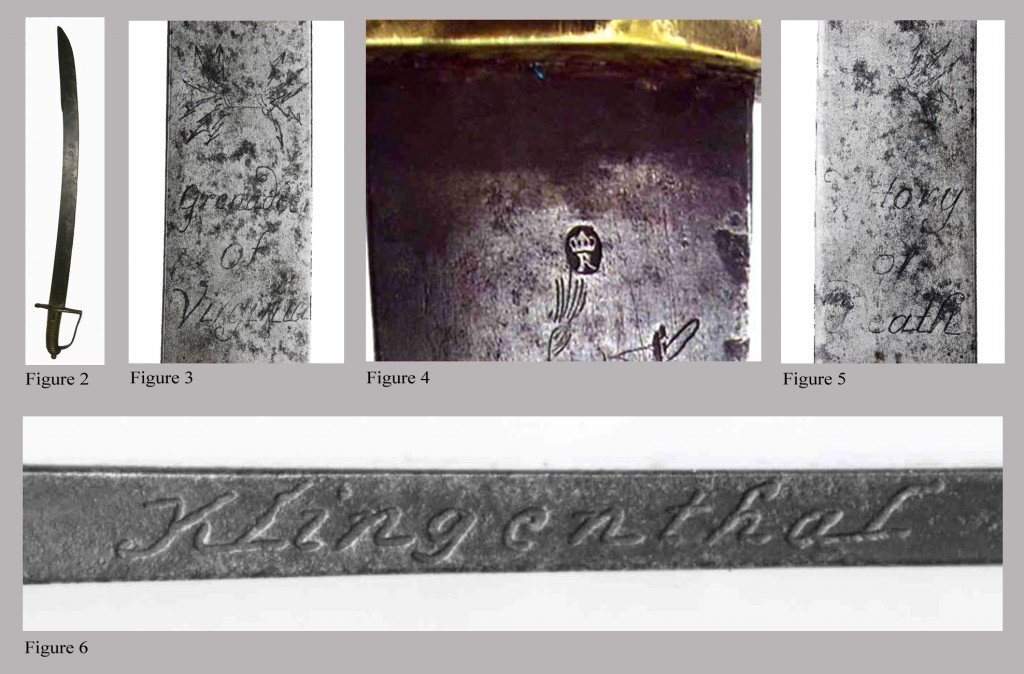

The first style of sword was the French grenadier hanger (Fig. 2, French grenadier hanger, 1779). These grenadier hangers had “Grenadeer [sic] /of/Virginia” and a panoply of arms inscribed on the obverse side of the flat blade, along with a blade hallmark placed near the hilt. This hallmark, consisting of a crown over an “R” within a small sunken oval, also was placed on all of the Virginia Klingenthal swords (Fig. 3, Obverse side of blade showing “Grenadeer of Virginia” markings on grenadier hangers) and (Fig. 4, Blade hallmark). The inscription “Victory/or/Death” and a different panoply of arms appeared on the reverse side of the blade (Fig. 5, Reverse side of blade showing “Victory or Death” markings on grenadier hangers). The manufacturer’s origin, “Klingenthal,” was inscribed along the top edge of the blade near the hilt. This marking also was similarly placed on all Virginia Klingenthal swords (Fig. 6, “Klingenthal” blade mark). The grenadier-style sword had the longer blade and usually measured approximately 26 ½ inches in length.

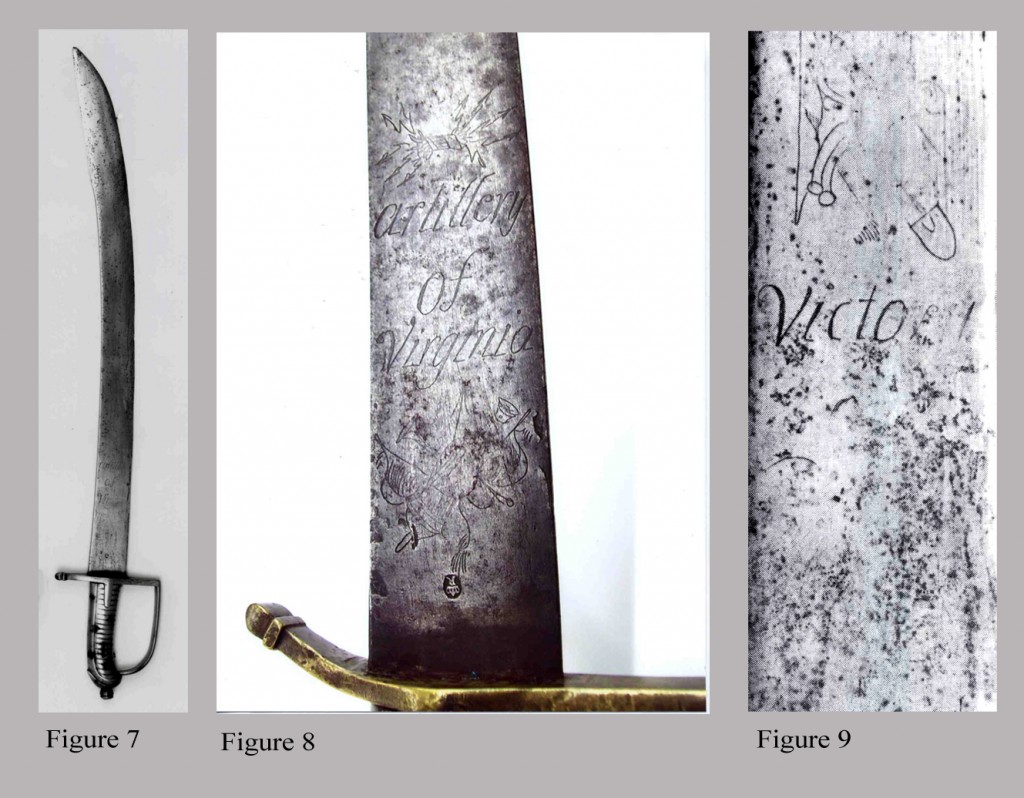

The second style of French Model 1767 hanger made for Virginia was an artillery sword (Fig. 7, French “Artillery of Virginia” hanger, 1779). These swords had “Artillery/of/Virginia” and a panoply of arms inscribed on the obverse side of the slightly curved flat blade (Fig. 8, Obverse side of blade, marking details on the artillery hanger, note the blade hallmark). The inscription “Victory/or/Death” with an artillery panoply of arms appeared on the reverse side of the blade (Fig. 9, Reverse side of blade, marking details on the artillery hanger). The origin, “Klingenthal,” also appeared along the top edge of the blade near the hilt. The artillery-style sword had a slightly overall wider or broader blade than the grenadier example and measured only approximately 23 ¾ inches in length.

The genesis of these blade markings is unknown. Both the grenadier- and artillery-style swords were originally carried in leather scabbards with brass tips.

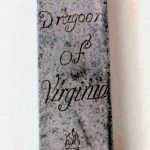

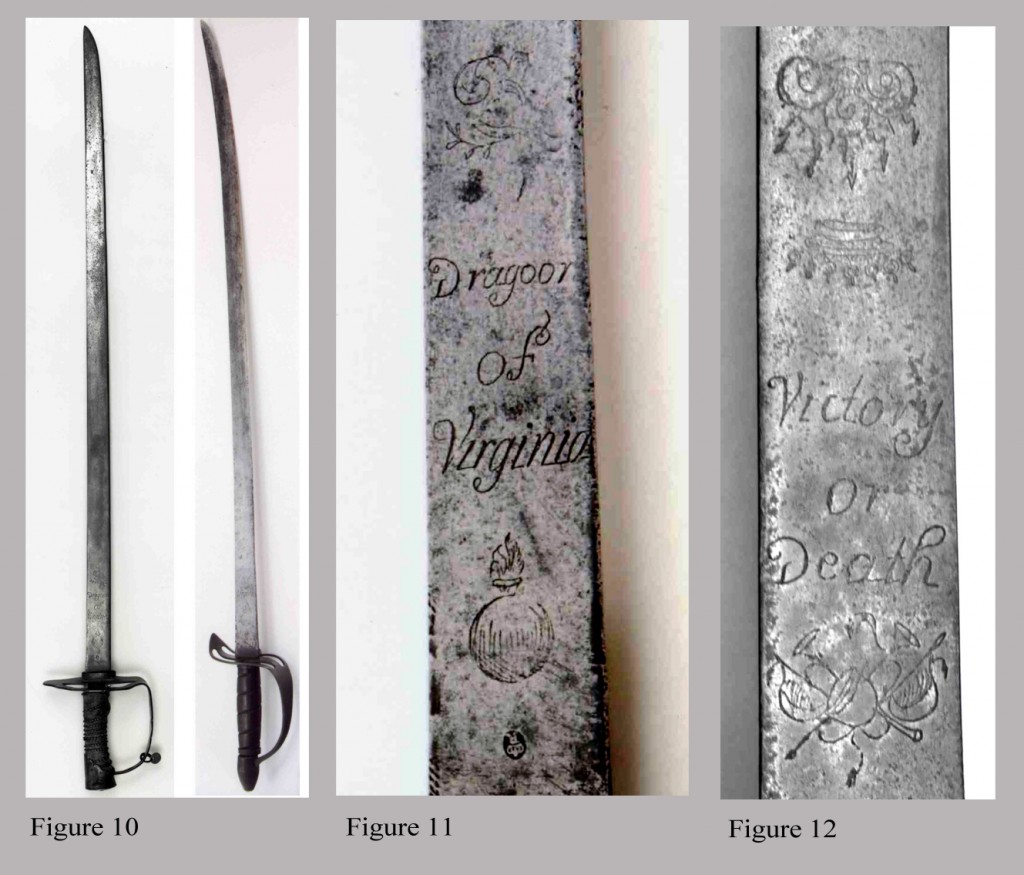

The third type of French sword imported to Virginia was a traditional horseman’s sword with a long, almost straight, narrow blade. These were for arming Virginia dragoons or mounted infantry troops (Fig. 10, Two, French-made, Virginia-dragoon sabers with Virginia hilts) (Sword on left is in the Collection of the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA). The lack of conformity in hilt design among the surviving examples suggests that many of these swords were hilted after their arrival in Virginia. Both iron stirrup and more traditional French guards in brass are known on these swords, and no single hilt design predominated. The brass French hilt on the Virginia sabers conforms to the French Model 1770 saber hilt, except on all known Virginia dragoon examples, the two side branches of the brass hilt have been removed leaving only the single “D-guard” branch intact. This removal of a portion of the guard was professionally accomplished so as to be barely detectable. I believe (but cannot substantiate) this alteration was performed in France rather than in Virginia. The work is very consistent and uniformly accomplished on all Virginia models. The handles were wood, and a few examples are known with leather covering and wire encircling the handle. The blade of the third type, or horseman’s sword, was practically straight, narrow, and 36 inches long. “Dragoon/of/Virginia,” a flaming bomb, and a visored helmet were inscribed on the obverse side of the flat blade, along with the identical blade hallmark seen on the grenadier and artillery examples (Fig. 11, Obverse side of blade, marking details on the dragoon sword, note the blade hallmark). The inscription “Victory/or/Death” and a panoply of arms appeared on the reverse side of the blade (Fig. 12, Reverse side of blade, marking details on the dragoon sword). As on all the French swords for Virginia, the sword’s origin, “Klingenthal”, was inscribed along the top edge of the blade near the hilt. The dragoon sword was carried in a leather scabbard with a brass tip.

The production of swords for Virginia began immediately, and the order was completed, probably by early 1779. Although the actual number produced is unknown, evidence based on shipping information and the scarcity of surviving examples suggests that only a very small number of all three types were manufactured. Likely no more than 1,500 to 2,000 swords of all three styles came to Virginia. No other successful contracts for these particular types of swords with the Virginia blade designations are known.

After their completion in early 1779, the swords, along with pickaxes, hatchets, and shovels began the long journey toward Virginia. From Klingenthal, the swords traveled to Strasbourg. From Strasbourg, the supplies were transported to the French city of Nantes near the coast. William Lee’s agent. John Daniel Schweighauer, of Schweighauer and Dolorex, assumed possession. Later, these supplies were transported from Nantes to the Isle Dey, near Brest, for their eventual ocean voyage to Virginia. A problem with the French officials regarding the duty on these items, as well as strong winds, prevented the sailing until 10 May 1779. 6 Of the large American fleet already at Brest, there were three vessels specifically destined for Virginia: the Hunter, Captain Robins; the Mary Fenron, Captain John Fulkard; and the Governeur Livingston, Captain Gale. All of Virginia’s military supplies of cannon and ordnance from the arsenals of King Louis XVI and the swords and other supplies from Klingenthal were shipped on board the Governeur Livingston. 7 This fleet, bound for America, was protected during the first part of its journey by a French convoy only as far as the French West Indies. After the fleet left the Indies without convoy protection, the Hunter was captured by the British. The other two vessels destined for America finally arrived without incident in August 1779. On 16 August, an announcement in the Virginia Gazette informed the public that the cargoes of both the Governeur Livingston and the Mary Fenron were in storage at Cumberland, located on the Pamunkey River in New Kent County, awaiting the owners’ payments of freight and other expenses. 8 Thirteen months had elapsed from the initial contract to the swords final arrival in the state.

The swords would have been distributed rapidly to the Virginia militia, and with the intensified British activity in the southern states by 1780, a large number of these weapons would have seen service in the Carolinas. The first direct reference to their service appeared at the Battle of Guilford Court House on 15 March 1781. During the engagement, the British captured Virginia Major Alexander Stuart. His artillery-style French sword with a damaged hilt is in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society. Another example of one of these French swords was excavated in 1974 near Williamsburg, Virginia, at the Kingsmill site near the James River in James City County.

Continued British designs on the southern states prompted Governor Thomas Jefferson to support General Baron von Steuben’s request for 200 additional cavalry, and in April 1781, the governor instructed the various militia lieutenants that “it will be necessary for the Troopers to mount and equip themselves. Some good swords it will be in our power to furnish, and all of them with a shorter kind. So that the want of that Article need not keep them from the field.” Later, on 22 April 1781, Jefferson specifically stated in his letter to the Council that these swords would be “Grenadier Swords.” 9 This important correspondence officially establishes the use of these short hangers for mounted use. Later, in May 1781, Jefferson again instructed the county lieutenants of the need for cavalry to confront the British advances. He advised that ”they must not be received however unless their horses are good and fit for service. A short sword can be furnished them by the State, tho’ if they can procure a proper one with other Equipments themselves they had better do it.” 10

An anticipated British raid on the continental arsenal at New London in Bedford County, Virginia, forced its commanding officer, Captain Bourn Price, commissioner of military stores, to remove continental supplies, along with some state arms located there. He reported on 22 July 1781 that during the removal and evacuation of supplies, only a few swords were lost and that a total of “557 Sergeant’s Swords” and other materiel had safely been removed to the state’s Point of Fork Arsenal in Fluvanna County. The terms, “Sergeant’s swords, cutlasses, ship swords, and boarding swords” were used frequently throughout the state’s arm records, and these terms were used in a loose sense during and after the Revolution to denote any short cutting sword.

The state’s arms facility at Point of Fork mentioned earlier continued to play an ever-increasing role in the history of Virginia’s weapons. During the first quarter of 1783, virtually all of the state’s military supplies located at various scattered locations, such as New London and Winchester, began moving slowly to the arsenal at Point of Fork. Materiel from the Fredericksburg Gun Factory joined other munitions at the arsenal. 11 For many years after the Revolution, the Point of Fork Arsenal was the only active repository in the state. In April 1791, for example, an arms return at the post noted that there were a total of 25 horseman’s swords and 1,214 “Sergeant’s Swords” on hand.

As the state’s only post-Revolutionary arsenal, the post also distributed weapons. In 1791, 18 un-hilted horseman’s swords were lent to a Captain Lewis of the Goochland troop of cavalry. He was instructed to have them well mounted at his own expense, but they were to be returned to the state upon request. Instances such as that one might explain the inconsistent hilt designs found on the “Dragoon of Virginia” swords.

The French swords were deposited in the loft of the arsenal building at Point of Fork, and a report in 1791 related: “In the same place [loft of the arsenal] are deposited the Sergeant’s swords, Pistols, Holsters, Horseman’s Caps, and Cartridge paper. The swords are generally very rusty and in bad condition.” 12 Workmen soon began cleaning the swords, and by December 1791, three artificers had finished 800 of them. The refurbishing and cleaning of the swords help explain the faint and often partially obliterated blade markings seen on many of the specimens today.

Beginning in 1801, all of the miscellaneous weapons at the Point of Fork Arsenal were sent to Richmond. The post was closed, and finally sold by the state in 1809. A total of approximately 900 swords of both grenadier and artillery styles were transferred to Richmond. Because the new armory, the Virginia Manufactory of Arms, begun in 1798, was not completed when the older firearms and swords began arriving in Richmond, the state deposited its arms into two separate facilities. Many of the firearms were placed into storage in the new penitentiary, located to the west of the armory building. The new, damp walls of the penitentiary storage areas were lined with plank in early 1801 to absorb the moisture in order to prevent the weapons from rusting. The swords, perhaps as an additional safety precaution, were placed in storage in the attic of the state capitol building, located to the north of the new armory building. These swords, with the exception of infrequent disbursements to militia units, remained in the capitol’s attic for several years.

Approximately 600 of the original 900 French swords remained on inventory in the capitol when 187 of the grenadier-style swords were withdrawn in 1806 by executive order. They were moved to the Virginia Manufactory of Arms, where there were un-hilted and cleaned with the purposeful removal of all previous blade markings, including the “Klingenthal” origin mark. New regimental designations were stamped on the top edge of the blades near the hilt, and the hilts were replaced onto the blades. New belts and scabbards with brass tips were provided, and the swords were packed into a single hogshead and shipped on board the sloop Nancy, Captain Addison, to the attention of the commandant of the 7th Regiment of Artillery in Norfolk County on 31 July 1807. He received a total of 80 refurbished French grenadier swords with the designation “7, V’A REG’T” for the noncommissioned officers in his command (Fig. 13, French “Grenadeer of Virginia” hanger with all original blade markings removed and Norfolk County regimental markings stamped on the top edge of the blade near the hilt) (Fig. 14, Detail of Norfolk County markings, “7, V’A REG’T”). The remaining 107 refurbished French swords marked “4, V’A REG’T” were to be delivered by him to the commandant of two artillery companies in the Borough of Norfolk. Only two of these 187 refurbished swords are currently known, and both are marked “7, V’A REG’T”. Interestingly, there are also two other swords marked “7, V’A REG’T” known, one grenadier-style sword and one artillery-style sword. In addition to the Norfolk County regimental markings, these two swords still retain all their earlier Klingenthal marks as well. Were these latter two swords part of the 187 ordered but were not ground for some reason? Why is there an artillery sword in the mix when the governor ordered 187 grenadier swords? Were they Virginia militia swords already in possession of the Norfolk County regiment that had been previously marked for the regiment? Answers to these questions will have to await future research. 13

Although, the Virginia Manufactory of Arms was producing iron-hilted, artillery swords by 1806, artillerists often preferred a brass-mounted sidearm that reduced the danger of accidentally creating a spark close to the gunpowder. 14

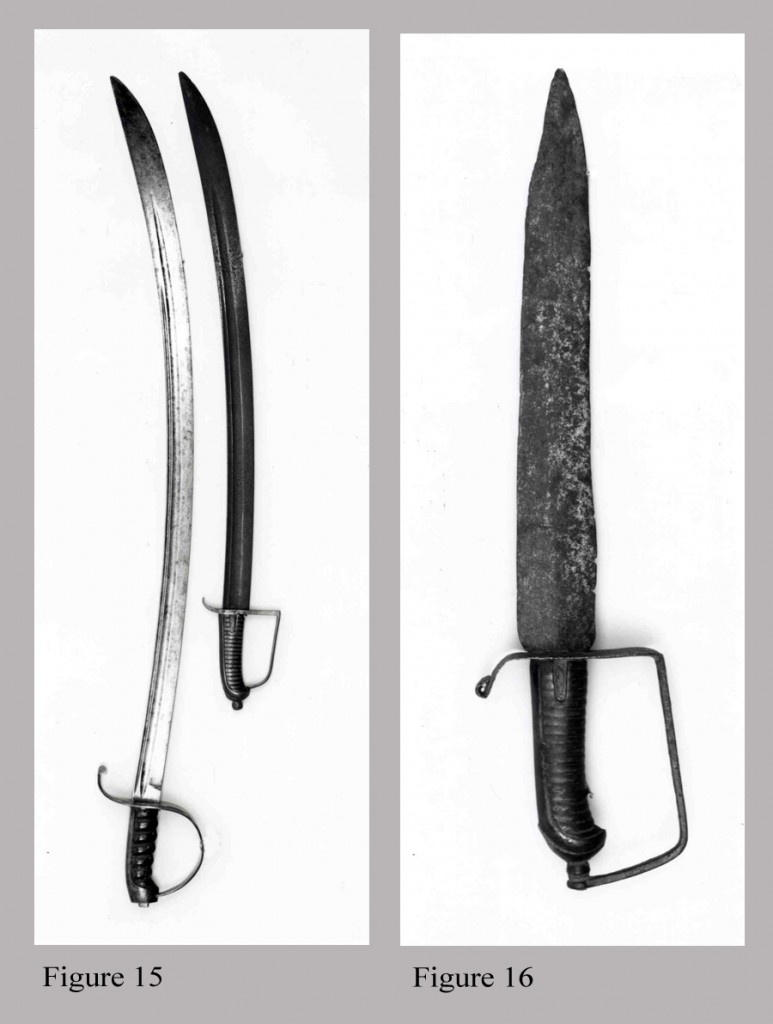

By 1808, the supply of surplus French swords finally had been exhausted in the state’s arsenals. However, some of these weapons were returned occasionally to the armory by the militia in exchange for the newer iron-hilted examples. Infrequently, altered examples are located, which continue to confirm the important role these early swords had in Virginia’s history. For example, one specimen is known that has the marriage of an early French brass hilt with a shortened First Model Virginia Manufactory cavalry sword blade (Fig.15, French “Grenadeer or Artillery of Virginia” brass hilt placed onto a shortened First Model Virginia Manufactory saber blade, c. 1806 [right]). Presumably, this is one of a very few examples altered at the armory in addition to the two Norfolk distributions. One of the latest alterations of these early French swords is the existence of a Confederate-made, D-guard, bowie knife comprised of an early French brass handle but modified with the addition of an iron guard and a short, hand-forged, knife blade. It is probably a one-of-a-kind piece using a section of a sword that was made over eighty years earlier (Fig. 16, Confederate, D-guard, bowie knife fabricated using the handle from either a French “Grenadeer or Artillery of Virginia” hanger, c. 1861)!

In conclusion, the imported swords from France served the state’s requirements for edged weapons long after their original intended purpose. Today, they have become important, scarce, and highly prized relics of Virginia’s past.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

Published on: Mar 8, 2015

Endnotes:

- Richard Henry Lee, Life of Arthur Lee (2 vols.; 1829; Boston, 1969), pp. 414-15; H.R. McIlwaine, ed., Official Letters of the Governors of the State of Virginia (3 vols., Richmond, 1929), 7 May 1778; Council Journals Volume 2, p. 96.

- Worthington Chauncey Ford, Letters of William Lee 1766-1783 (3 vols.; New York, 1968), 2:446; Letter book of William Lee, 2:24, Virginia Historical Society.

- Letter Book of William Lee, 2:33.

- Ibid., p. 37.

- George C. Newman, The History of the Weapons of the American Revolution (New York, 1967), p. 216.

- 6. Life of Arthur Lee, p. 429.

- Ibid., p. 640; Alonzo T. Dill, William Lee Militia Diplomat (Williamsburg, 1976), p. 32.

- Virginia Gazette (Clarkson & Davis, 16 August 1779; Executive Papers, 24 September 1779, Reel 1, Library of Virginia.

- McIllwaine, ed., Official Letters, p. 468; Council Journals, 2:339.

- McIllwaine, ed., Official Letters, p. 507.

- Ibid., p. 459.

- Executive Papers, January-May 1791, Box 69, Library of Virginia.

- Executive Letter Book, 28 October 1806, Reel 7, Library of Virginia; Letter Book of John Clarke, 29 November 1806 11 June 1807, 31 July 1807, Library of Virginia; Swem No. 217, Box 2, pkg. no. 3, Library of Virginia; Council Journals, 17 April 1807, p. 79, Reel 8, Library of Virginia.

- John Hamilton, Man at Arms, Volume 5, no. 4, July-August 1983, p. 48.