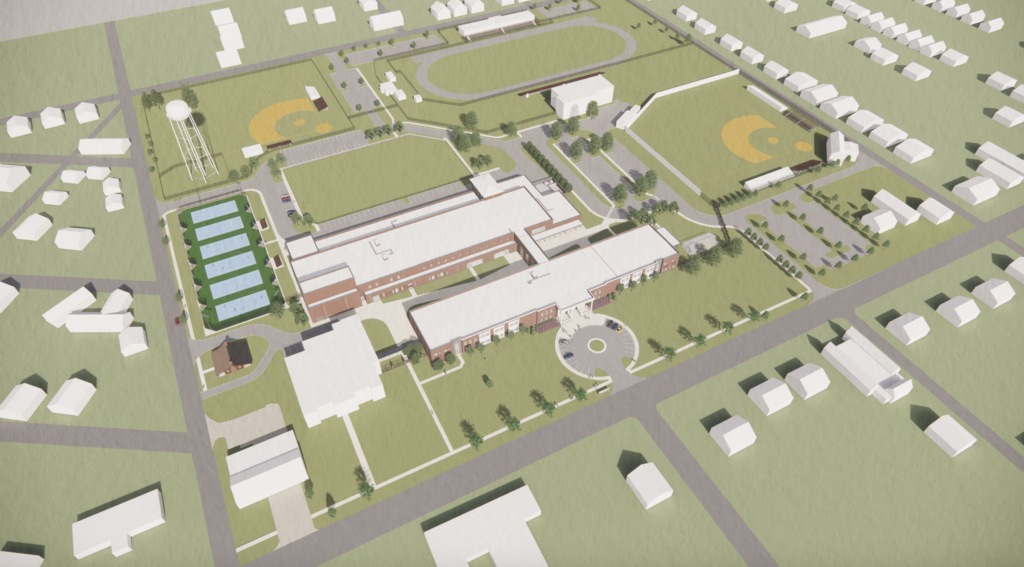

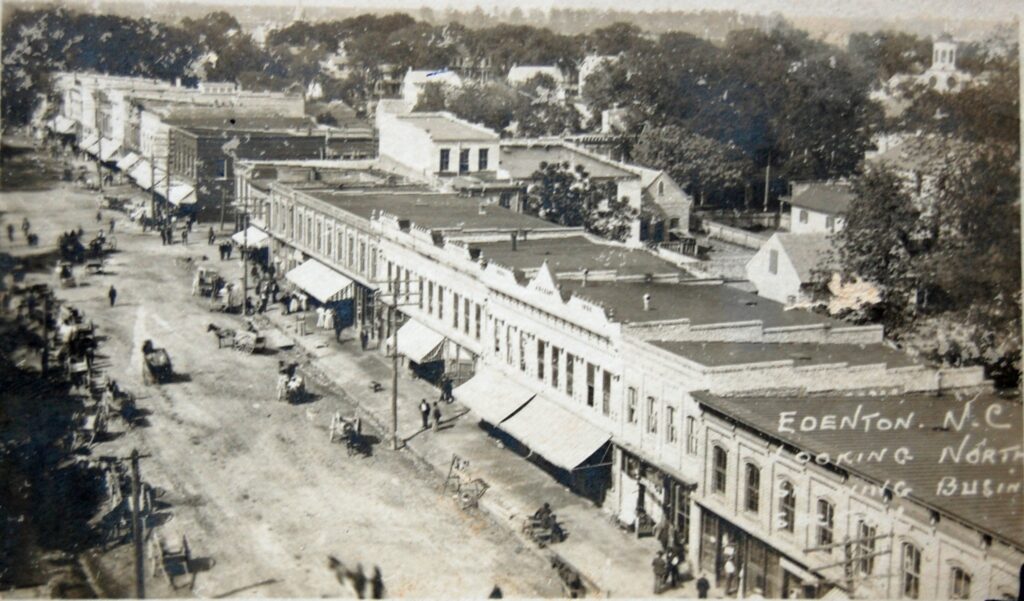

In January and February 2023, we ran a multi-part social media series on the history of the Town Common in Edenton-a track at the northern end of Broad Street that is the home of the John A. Holmes High School campus, the former National Guard Armory, Historic Hicks Field, and the 1929 Boy Scout Cabin. This series was created to add to the discussion about the construction of a new John A. Holmes High School.

Below please find the complete series, which traces the Common from its creation in 1723 as a 100-acre public space for “Estovers & Pasturage” to its present 40-acre campus in the heart of our Town.

Part One

As this section of Town is now part of significant discussion, we’d like to explore its history from the very beginning to the present. Over the next two weeks, we will share how this area changed over the last 300 years in tandem with our community.

So, before we can dive in, we have to ask, what is a “town common”?

A town common is, in a nutshell, public land/land set aside for public use.

A holdover from traditional English urban planning, commons are typically seen in communities first established as colonial settlements. While most American commons are in New England, there are a few examples in the mid-Atlantic area and the South, including ours here in Edenton.

Part of a 17th and 18th century community structure, a common could technically be a piece of public land of any size within the city limits, and could be used for a variety of purposes, including green space, gathering areas, and burial grounds. A common tended to be bounded on at least one side by residential property.

Consider how the Courthouse Green, part of Edenton’s 1712 “Old Plan”, continues to serve as a type of common where people can gather and enjoy outdoor recreation, whereas the St. Paul’s graveyard was laid out in the 1722 “New Plan” as a public burial ground.

Yet the Town Commons at the northern end of Town has always served a different purpose, and has been adapted over time to meet the other needs of the community.

On August 11, 1723, Robert Hicks transferred a parcel of land at the back of the Town to Edenton, “…for the better accommodating of the said Town with Common…to encourage the further settlement thereof…” The deed also stipulated that the land was to be used for the “…benefit and behoove of the Freeholders and Inhabitants of said Town…to lie perpetually as a Common for the use of said Town…” (Deed Book C-1).

So by the end of 1723 Edenton had a good bit of public land, but how were residents going to actually “benefit” from it?

That is also answered by the original deed-”Estovers & Pasturage”!

Part Two

We have learned that on August 11, 1723, Robert Hicks deeded a parcel of land to the Town of Edenton “…for the better accommodating of said Town with Common of Estovers & Pasturage…” (Deed Book C-1).

It sounds like the Town Common was to serve as an amenity, but what do the terms “Estovers & Pasturage” mean?

Long before the days of automobiles and grocery stores, most residential properties in villages and small towns were laid out as homesteads, with a main house, gardens, some outbuildings, and…chickens?

Oh yes-back in those days, many households-from the modest to the affluent, from those that relied on the forced labor of enslaved persons to those that did not-kept chickens and even pigs.

Apparently, hogs running wild became such a problem in early North Carolina settlements that in November 1723, the General Assembly voted that any hog, pig, or shoat not kept in “…Close penns or Styes…” could be confiscated and sold for the benefit of the poor.

In any case, while some goods were available in the Market House, many families relied on staples produced at home-a tradition that continued even into the early twentieth century.

Some properties in colonial Edenton also had stables for cows, horses, donkeys, etc. It’s here that we come to the Town Common as a “Pasturage”, for this public land provided the essential area for these animals to graze freely.

Now onto “Estovers”-this is an old word from England’s feudal period, and means “necessities”, or the right of a tenant to take wood from a landlord’s property for fuel and/or building materials. For Edenton in 1723, this meant that the residents could harvest wood from the Town Common.

Yet the Town Common wasn’t just used for “Estovers & Pasturage”-in the next few posts, we’ll explore how the Common became a further focus of community life, a center for education, and the location of a new beginning for many of Edenton’s Freedmen and -women.

Part Three

The year is 1779. The fledgling United States is still fighting for her independence from Great Britain, and the Constitution will not be put to paper for another 8 years.

North Carolina’s General Assembly must now pass state laws instead of provincial ones, and has many matters of importance to handle in its October-November session.

Among them is a matter so crucial, that it is established by a formal Act of the Assembly:

The creation of…A FAIR!

Yes indeed, Edenton and Chowan County’s favorite part of the year goes almost as far back as the birth of our nation, though admittedly without the rides and game booths.

In the “Act for Establishing Fairs in Halifax Town and Edenton”, the Assembly voted that:

“…fairs shall and may be held in the said towns of Halifax and Edenton twice in every year, viz. on… the second Thursday in May and November in Edenton, each fair to continue for three days, for the sale of every kind of horses, black cattle, sheep and hogs, pork, and all kinds of provision, tobacco, and every other natural production of the country, and also for the sale of all and every sort of goods, wares and merchandise, whether foreign or manufactured in this State…

…and that on the said Fair days…all persons coming to, being at, or going from the same…shall be free and exempt from all arrests, attachments, and executions whatsoever, except for capital offenses, breaches of the peace, or for quarrels or controversies that may arise during the said time…”

The Assembly also made provisions for horses to be registered prior to sale, and designated 5 people from each town to judge disputes.

And which area of Town could accommodate such festivities? The Town Common, of course!

As things changed over the years, general market days became more common (sorry), and centered on the Courthouse Green. But, as we will soon learn, post-Civil War Edenton re-embraced the traditional Fair format, and in a way that had some big implications for the Common.

But first, we need to learn about the first school on the Town Common!

Part Four

Thus far we’ve seen how the Common was used to accommodate the basic needs of everyday life, but with a new nation came new horizons, and in 1785, the General Assembly was ready to expand a major initiative: education.

Education had been offered in Edenton in some form since its early days-in 1745, Governor Gabriel Johnston even passed an act empowering the Edenton Town Commissioners to build a formal school-house (potentially the small structure on West Gale as noted by the 1769 Sauthier map of Edenton). In 1770, the Governor and General Assembly further vested two new lots purchased for the “school at Edenton” in Trustees.

Yet near the end of the Revolutionary War, this school may not have been enough to serve the growing population of young people in Edenton, for in 1782, the General Assembly voted to incorporate “Smith’s Academy” as a “public seminary of learning”.

And where was this “public seminary of learning” located?

In 1785, the Assembly authorized the Town Commissioners to convey part of the Town Common to the Trustees of Smith’s Academy, so that they may “erect public buildings” for the institution there.

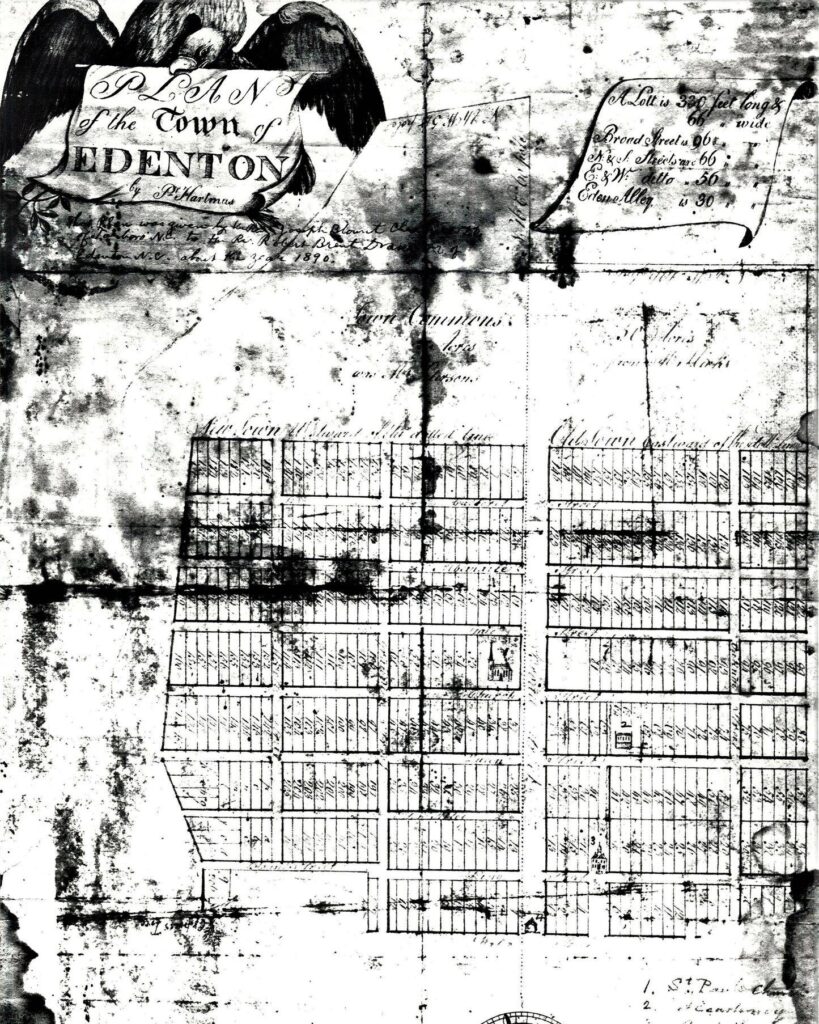

Smith’s Academy unfortunately did not seem to last long, for in 1800, the Assembly incorporated Edenton Academy, and noted that a few lots between Queen and Church Streets had been purchased for its construction. The Academy is visible in this location on the attached fragment of the ca. 1810 Hartmus Map, which shows that the Town Common was, at this point, still relatively open.

Though short-lived, Smith’s Academy shows that the Town Common hosted “public” education long before the construction of John A. Holmes!

But it was not the only school on the Common to predate the High School-something truly ground-breaking was on the next horizon…

Part Five

One of the many evils of American chattel slavery was the extent to which state governments endeavored to prevent enslaved individuals from learning how to read and write.

In 1830, North Carolina’s General Assembly passed a law stating that “…the teaching of slaves to read and write has a tendency to excite dissatisfaction in their minds and to produce insurrection and rebellion to the manifest injury of the citizens of this state…”, and that a free white person so convicted of this “crime” would be either heavily fined or even imprisoned.

Under the same law, should a free person of color or an enslaved person be convicted of teaching an enslaved person to read, they would be “…whipped at the discretion of the court not exceeding thirty nine lashes nor less than twenty lashes.”

Hence it should come as no surprise that when freedom came, one of the first priorities of the new communities of Freedmen and -women was to establish schools.

We actually have quite a few sources that confirm the existence of a Freedmen’s School here in Edenton, including a letter from an author who was high profile even at the time-Harriet Jacobs!

Yes, indeed-the Edenton-born abolitionist and author of the internationally-circulated autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl”, returned to her grandmother’s house on West King Street in 1867. While there, she visited friends and family, and retraced her steps from her harrowing years as an enslaved woman and mother.

In her April 25th letter to Ednah Dow Cheney, secretary of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society, Harriet mentions how “…there is one School in Edenton well attended…”, and discusses the general desire for “Plantation schools” out in the County.

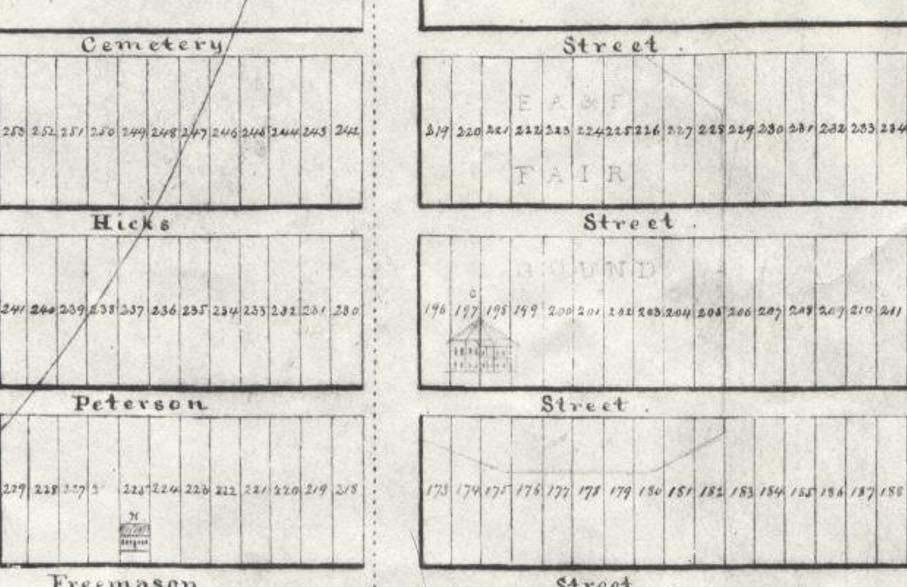

And where was this school in Edenton located? According to the research conducted for “The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers”, on October 23, 1866, the Town Commissioners “…ordered that the freedmen of the Town of Edenton be allowed to build a Schoolhouse in the Town Commons east of Oakum Street.”

Part Six

We have learned that Harriet Jacobs visited the Freedmen’s School in Edenton in 1867, and that the School was located on the Town Common.

While we know that the Town Commissioners voted to allow the “freedmen of the Town of Edenton” to build a school, who undertook such a momentous task?

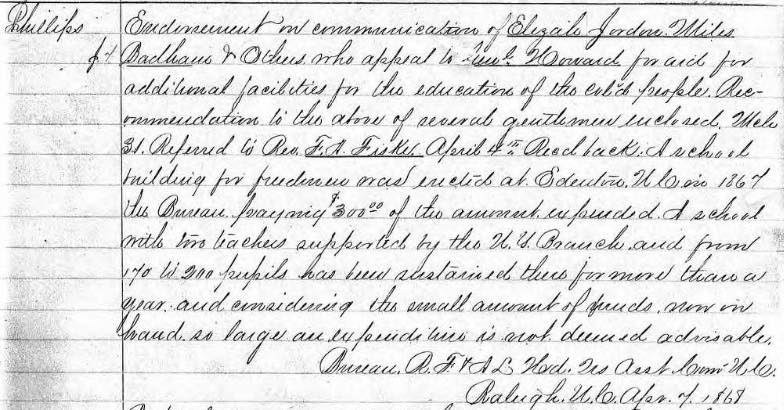

In the newly digitized records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, we discovered a record that suggests that the School was built by Miles Badham!

Born into slavery at Hayes, Miles Badham was a highly skilled carpenter and the patriarch of the Badham family of builders. His son, Hannibal, would later construct the gorgeous Queen Anne-style houses on East Gale Street, and is credited with the construction of the Kadesh AME Zion Church. Hannibal and his wife, Evalina, were pillars of the community, and this civic spirit likely originated with Miles.

The correspondence ledger for the Freedmen’s Bureau records that on April 7, 1868, a reply was sent to a letter received a few days prior. The record states that the Bureau received,

“…communication of Elizabeth Jordan, Miles Badham, and others who appeal to (Lieut?) Howard for aid for additional facilities…A school building for freedmen was erected at Edenton , NC in 1867…A school (illegible) two teachers supported by the US Branch and from 170 to 200 pupils and has been sustained there for more than a year…”

Further Bureau records show that the building was “owned by freedmen”, and that it could hold up to 80 scholars at once. Classes were not only restricted to children, but night and Sabbath schools also operated out of the building to teach adults.

While we do not know for sure what happened to the School after the dissolution of the Freedmen’s Bureau, we know from the A. T. Bush Map that by 1895 a new school for non-White children had been built on West Freemason Street.

So the Town Common had developed from an early eighteenth century pasture for livestock and resource for firewood to the site of public education. But remember, we mentioned that it had another purpose, and that it would return in a big way…

Part Seven

Who else loves the Fair?

While the Town Common saw government-mandated fairs in the eighteenth century, it became the epicenter of a new experience in October of 1889: The Edenton Agricultural and Fish Fair!

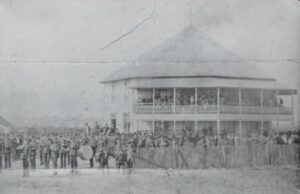

Built by Theo Ralph and his team in the previous summer, the focal point of the “Fairgrounds”-the semi-official name of the Common-was an octagonal Exhibition Hall overlooking a racetrack for horses.

Yes, indeed-these nineteenth century fairs had horse racing! And this was no amateur hour-winners could receive prizes up to $100.00, or $3,226.05 in today’s terms!

With such stakes, it’s not surprising that the Agricultural & Fish Fair drew massive crowds from the whole region, and Norfolk & Southern even offered railroad and ferry tickets at reduced rates.

The Exhibition Hall was filled to the brim with all sorts of prize-winning entries, from baked goods to perfect vegetable specimens and more. Local bands also performed on the grounds, and multiple speakers addressed the crowds.

This first Fair even boasted a massive Fair Ball, where local residents and visitors danced the night away in their finery.

The Edenton Agricultural & Fish Fair lasted into the early twentieth century, but the Great Depression, which changed so many things in Town, shifted the region’s focus to the State Fair for a number of years. Thankfully, our community’s beloved Fair was later revived by the American Legion.

While the Exhibition Hall appears to have been demolished by the 1930’s, the Common continued to be known as “The Fairgrounds” until the American Legion established the current fairgrounds in the 1950’s.

Part Eight

As the Great Depression loomed, Edenton was yet again moving into a new chapter.

The post-Civil War decades had changed the Town from a quiet agricultural center into an industrial powerhouse and the State’s cradle of historic preservation.

With the introduction of the railroads and steamship ferries, factories emerged on the outskirts of Town, creating more jobs for blue collar workers, and expanding local and regional markets.

Entrepreneurs built lavish homes throughout the Historic District, and a host of builders rapidly expanded housing into North Edenton, helping the western part of the Common’s original 100-acre lot become one of the main neighborhoods for Edenton’s rising Black community.

The 1880’s and 1890’s also saw a surge in Black entrepreneurship, and these businessmen and -women believed in empowering their community. Not only did they financially support the construction of new churches, but they also participated in civic organizations and broadened the horizons of students.

Unfortunately, as in much of the country, North Carolina law sought to put a stop to this progress, and in 1899 the General Assembly drafted an amendment to the State Constitution designed to disenfranchise Black voters, which ultimately passed in the following year.

Thus came the dawn of the twentieth century-not with equality for all, but with the rise of Jim Crow.

Over the next few years, the community endured even more hardship and setbacks, bidding farewell to its sons during the Mexican Border War and World War I, and suffering the fear and loss of the Spanish Flu pandemic.

Hence it’s understandable how in the 1920’s, Edenton was ready for some positive change. The first floor of the Cupola House, saved in 1918, was adapted into the Town’s first public library, and the Taylor Theater was constructed on Broad Street to provide cutting-edge entertainment.

The remaining portion of the original Town Common also received renewed attention, and in 1929, it became the home of something that may have been built for Edenton’s youth, but became an idyllic symbol in the years to follow.

Part Nine

Yesterday we learned that by the 1920’s, Edenton was ready for some positive change. In the Town Common and immediate neighborhood, this new chapter was heralded by two new structures.

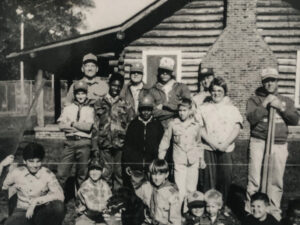

First, in 1929, J. A. Woodard funded the construction of a log cabin on the Common facing Broad Street, which was to be the “romantically rustic” headquarters of Edenton’s local Boy Scouts.

The Boy Scouts of America organization was established in 1910 in response to the growing trend of families leaving the countryside and moving to cities. Scouting offered young people the chance to learn practical life skills while developing community mindfulness and civic pride. This blend of classic American values resonated with families throughout the country, and in 1914, the first Troop was established in Edenton.

The Edenton Boy Scouts managed their long hikes and campouts for 15 years without a central office, but as their ranks continued to grow, so did their need for a headquarters. The little log cabin was built amidst the old grandstands of horse races past, and against the backdrop of the railroad track and veneer mill at the Common’s northeast corner.

When the local economy was threatened in the Great Depression, Scouting offered some relief, and gave the community further cause to come together. The cabin held some of Edenton’s future in its walls, and thus some of its hope for better times.

The next structure to herald major change was the Edenton High School, built in 1932 to consolidate some of the Town and County’s Black schools. The School was built on North Oakum Street with support from the Rosenwald Fund, and marked a profound advancement in local Black education, which had been hindered by a lack of resources. The School would later be named in honor of its long-serving principal and most famous educator, D. F. Walker.

The Edenton High School signified a major victory for Edenton’s Black community leaders, particularly the Reverend Simeon Nathaniel Griffith, who we’ll revisit later.

Part Ten

In the Fall of 1929, the stock market bubble of the Roaring Twenties finally burst, sending the United States into The Great Depression-an economic recession so terrible that the fallout would last through the end of the next decade. President Herbert Hoover’s popularity plummeted as newly destitute families realized that the White House was apparently carrying on as normal. Thus in the election of 1932, the American people chose a new leader with a promising potential solution: New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.

When the new President Roosevelt took office, he started work on the “New Deal”-a series of progressive acts that would support the struggling agricultural sector, regulate securities, and reduce tariffs to revitalize trade. In 1935, his administration also established an agency that would provide millions of jobs and form one of the greatest public works initiatives in American history-the Works Progress Administration, or WPA.

Over its eight-year span, the WPA not only improved the nation’s infrastructure, but also preserved her history and culture. Under Federal Project Number One, the WPA employed almost 40,000 artists, musicians, historians, authors, and other humanities-based professionals to create and document essential aspects of American life.

For Edenton, WPA funding was so much more than an economic stimulus-it accelerated the Town’s modernization. Through working with the WPA, the Town was able to pave its main streets, build a new Post Office, and improve other areas of infrastructure.

But the Common would see the most dramatic change, for in 1936, the Town won special funding to build a new National Guard Armory next to the Boy Scout Hut, and in 1939, the WPA constructed Hicks Field. These structures quickly became integral to the community’s life, as the Armory hosted sports matches and dances for both the Black and White schools, and Hicks Field enabled Edenton to come together in the name of enjoying “America’s pastime”, baseball.

It was during this time that the Town revisited another major goal-securing funding for a new high school.

Part Eleven

Whether intentionally or not, by 1950 the country had fundamentally changed. World War II and its atrocities had shaken the nation to its core, and the task of moving forward was fraught with the question of what our society could be and should be. Veterans who, while abroad, had been hailed as liberators regardless of skin color returned to segregation, women who had entered the workforce during the War were displaced, and the acknowledgment and treatment of post-traumatic stress had to make way for the idealized image of the “American Dream”.

As in previous pivotal moments, Edenton decided it was once again time to reconcile its current state and future goals, which meant that it was also time to revisit the quality of its educational offerings.

Prior to the War, the Town had constructed a large school for White students on the former site of the Edenton Academy, a school for Black students behind the Common with assistance from the Rosenwald Fund, and a White high school out in the County with assistance from the WPA (located at the current site of the middle school).

As the White school in Town had to accommodate both grade school and high school students, by the end of the War it was “bursting at the seams”, and the community was clamoring for a new high school.

While in the 1940’s there had been talk about building the hospital on the remaining portion of the Common, the public made its preference clear-the remainder of “Hicks Field” was to be the home of the new school.

Construction started by 1950, and classes were moved to the new building in 1952. In 1959, it was named for the Edenton-Chowan district’s long-serving Superintendent, John A. Holmes. Although the landmark case of “Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas” mandated integration, the decade closed on an Edenton that still had separate schools.

But the impending reckoning between the nation’s founding promise of equality and the discordant reality of segregation could not be postponed forever, and the Town Common was about to become the focus of a new push for change-the Civil Rights Movement.

Part Twelve

As in other states, the process of school integration was slow in North Carolina. Although the Supreme Court struck down “separate but equal” as established by “Plessy v Ferguson” in the 1954 ruling for “Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas”, some school districts in the state would not achieve full integration until the 1970’s. The delay came through the Pearsall Plan, the Pupil Assignment Act, and other legislation designed to put off enforcement, and the process did not pick up much steam until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Frustrated with this setback and the other hardships of life under segregation, Edenton’s Black community began to form organizations to protest inequality and injustice. By 1960, many of these groups formed a coalition called the “Edenton Movement” to better coordinate their efforts.

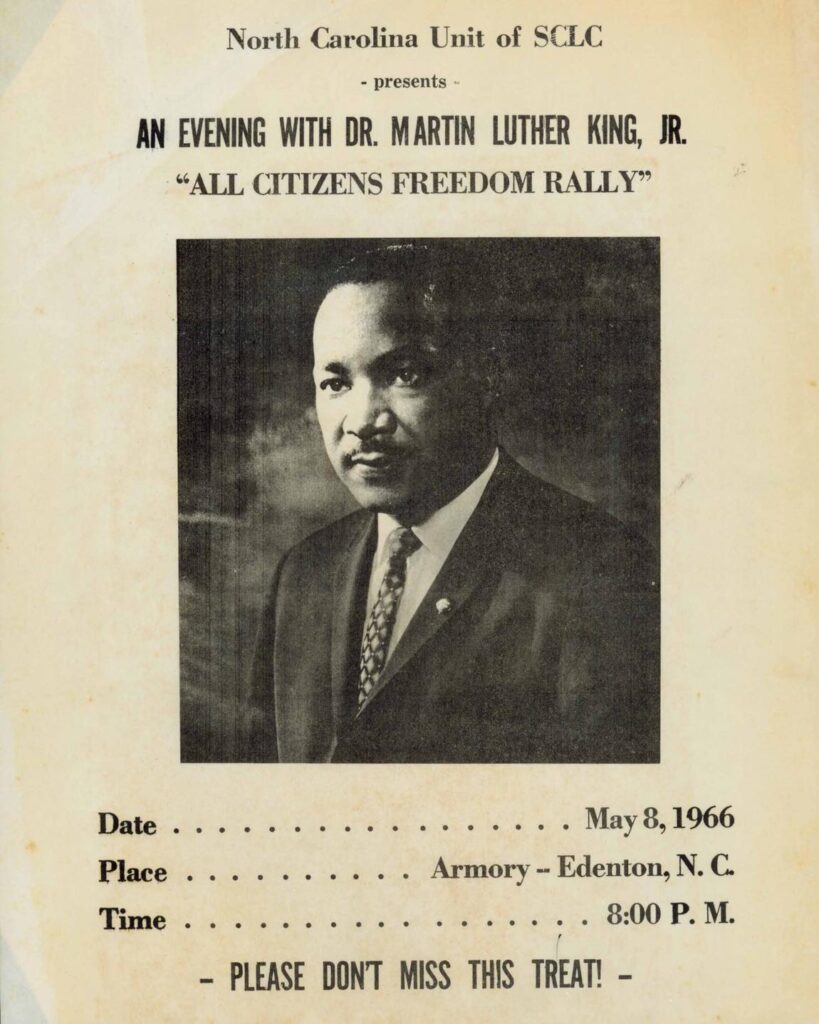

In 1962, the Edenton Movement successfully arranged for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to visit Edenton, and on December 20th he spoke to a massive crowd at the National Guard Armory on the Common.

According to a 1995 interview with activist Golden Frinks, Dr. King praised the Movement for its work, and called for change via passive resistance tactics such as economic boycotts, increased voting, and updated legislation.

Less than a year after this visit, the John A. Holmes High School was integrated by ten students from the Black community.

Despite this step forward, the push for Civil Rights still had to overcome many obstacles, and Dr. King made a second visit to the Armory in 1966.

While JAHHS had been partially integrated in 1963, over the next few years, the School Board attempted to delay full integration. Finally, a ruling from a US District Judge pushed the Board to finalize full-scale desegregation of Edenton-Chowan school district in time for the 1969-1970 academic year.

The Edenton Movement went on to realize yet more victories in the struggle for equality, successfully desegregating local businesses, the library system, and the Courthouse, and achieving representation in the workforce.

Part Thirteen

One of the leaders of the Edenton Movement was the long-serving pastor of the St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church, Reverend Simeon Nathaniel Griffith.

Born in Guyana in 1885, Rev. Griffith came to the U. S. in 1905 to pursue a higher education. After earning his bachelor’s from Shaw University, he went to seminary and was ordained in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York in 1914.

Intending to become a medical missionary in Africa, he entered the Boston University School of Medicine, but was later assigned to the parish in Edenton.

When he arrived in the early 1920’s, he decided to focus his efforts on northeastern North Carolina. In 1922, he married Mattie Lee Moye of Greenville, and together they began to build up their community.

Not only did Rev. Griffith serve as principal for multiple schools in the district, but he also became a pillar of the community, working to lift up families from poverty, serving on the boards of civic organizations, advocating for improved infrastructure in historically Black neighborhoods, and raising funds for charitable causes.

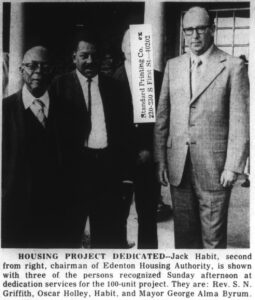

As a local leader, Rev. Griffith was instrumental in securing the new, consolidated Rosenwald school that would become the D. F. Walker High School. In 1932, Rev. Griffith also took the lead in developing a park for Edenton’s Black community on the Town Common at the corner North Oakum and East Freemason Streets.

Since Rev. Griffith had been advocating for better treatment of the Black community since the 1920’s, he naturally became a leader during the Civil Rights Movement. Not only did he help to welcome Dr. King to Edenton in 1962, but he also became one of the first Black residents to run for Town Council since the rise of Jim Crow, vying for the Fourth Ward in 1963.

Rev. Griffith’s years of service to his community were honored in two major ways. First, in 1972, one of the new housing developments was named “Griffith Place” in recognition of his humanitarian work. Second, in 1981, the park which he had started almost 50 years before was named “Griffith Park” in his honor.

Rev. S. N. Griffith passed away in 1983.

Part Fourteen

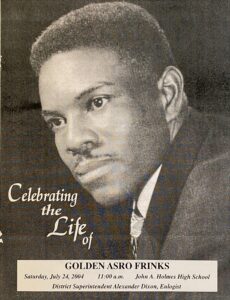

On July 24, 2004, hundreds of mourners gathered in the John A. Holmes High School for the funeral of activist Golden Asro Frinks.

Known as “The Great Agitator”, Mr. Frinks coordinated and participated in countless Civil Rights demonstrations across the Southeast.

A veteran of World War II, Mr. Frinks first got involved in the Civil Rights Movement a few years after he was honorably discharged, as he realized that not all of our nation’s heroes were treated equally and with respect at home. While studying in Washington D. C., he participated in his first sit-in, and there learned the power of nonviolent resistance tactics.

Back home in Edenton, he joined the local chapter of the NAACP, and began his long fight to end institutional discrimination. He picketed in front of local businesses that practiced segregation, organized sit-ins, and spoke at rallies and inspired others to promote change.

When the Edenton Movement formed, he was selected for a leadership role, and worked alongside Rev. Frederick LaGarde of the Providence Baptist Church to coordinate protests.

In 1962, Mr. Frinks and Rev. LaGarde joined Rev. S. N. Griffiths and other local leaders to welcome Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Edenton. Shortly after his visit, Dr. King asked Mr. Frinks to accept a leadership position in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

As part of the SCLC, Mr. Frinks served as an organizer for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Dr. King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

Mr. Frinks traveled extensively over the years, supporting the cause of equality under the law wherever he was needed. By his count, he was arrested 87 times during his period of activity. He later received multiple awards and other forms of recognition for his work, and is remembered as one of Edenton’s most influential figures.

His life was celebrated on that July day in 2004 in one of the great symbols of the success of the Edenton Movement-an integrated John A. Holmes High School.

The “Freedom House” of Golden Asro Frinks is currently being restored by the State of North Carolina.

Conclusion

Edenton’s Town Common has undergone a substantial transformation over the past 300+ years, from a massive field at the edge of Town to the site of public entertainment and the seat of public education. It has always been a focal point of change, reflecting Edenton and the country’s ongoing journey towards forming “a more perfect Union”.

Yet what binds this long history together is the Common’s original purpose-a place to be used for the “benefit” of the inhabitants of Edenton. Indeed, the long years of service of its primary structures-the 1929 Boy Scout Cabin, the 1936 National Guard Armory, the 1939 Historic Hicks Field, and the 1952 John A. Holmes High School.

As our Town stands at yet another pivotal moment, we are proud that these important historic structures can stand alongside a new John A. Holmes High School.