Joseph Hewes, a newcomer to Edenton signed the Declaration of Independence and as detailed in NCPedia:

Joseph Hewes, a newcomer to Edenton signed the Declaration of Independence and as detailed in NCPedia:

“Joseph Hewes, merchant, colonial leader, delegate to the Continental Congress, and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was raised at Mayberry Hill, the family’s 400-acre plantation near Kingston, West Jersey. He was the oldest son of Aaron (1700–53) and Providence Worth Hewes.

Hewes was born on July 9, 1730. The Chesterfield Monthly Meeting (Burlington, New Jersey) minutes list a “Joseph Hughs” born to “Aaron & Providence” as being born on the “28th day of the 4th mo., 1730.” In 1750, the British government reformed the Julian calendar to the modern Gregorian calendar. Under the Julian calendar, the fourth month of the year was June. Hewes was born under the Julian Calendar date of June 28, 1730. Under the reformed and modern Gregorian Calendar, Hewes’s birthdate translates to July 9, 1730.

Hewes was raised in a Quaker household and was likely taught a duty of public service and an appreciation for success through hard work. Following his education at the Kingston Friends’ Grammar School in 1749, Hewes apprenticed himself to Joseph Ogden, a relative and successful merchant-importer in Philadelphia. From August 1749 to September 1754, Hewes learned the trading business from dock laborer to cargo master. He refused a partnership offered by Ogden and, aided by funds from his father’s estate, established his own trade business in Philadelphia. Discouraged by a lack of success, he began to consider relocating his business to another town. His choice was Edenton, N.C.

Hewes arrived in Edenton in early 1755. In the spring, he entered into partnership with George Blair and Charles Worth Blount, both prominent merchants. The firm of Blount, Hewes and Company prospered, and by 1757 Hewes found time for political and civic affairs. That year he was appointed a justice of the peace for Chowan County and inspector for the Port of Roanoke. He also became an early leader in the movement to establish an academy in Edenton, a member of the building committees for the county courthouse and jail, and an official of St. Paul’s Parish.

By 1760 Hewes had gained a position among the elite of Edenton society. No doubt his status was enhanced by his engagement late in that year to Isabella Johnston, the younger sister of Edenton lawyer and political leader Samuel Johnston. Although Isabella’s death within the year brought this relationship to a tragic end, Johnston continued to consider Hewes as a member of his family. In 1760, Johnston, who had served as Edenton’s representative in the Assembly since 1754, convinced Hewes to stand for the borough seat. Thus began the merchant’s career in politics that would run with few interruptions until his death about twenty years later.

Hewes’s business ability was recognized by his fellow representatives, and he was repeatedly appointed to appropriation and finance committees. In filling these and other committee posts, he became intimately involved in the often bitter legislative-executive contests over the power to originate appropriation bills, audit accounts of public expenditures, issue paper currency, collect and appropriate quitrent revenue, to appoint and instruct the provincial treasurers and agents, and structure the colony’s judicial system. Although his service to the colony was exhaustive, Hewes did not neglect the interests of his constituents. From 1760 to 1774 he sponsored local bills to finance construction of a courthouse, church, and academy; to reorganize the town’s court and tax system; to improve navigational aids in the Albemarle Sound and Edenton Bay; and to regulate the inspection of exports through the Port of Roanoke.

As the movements towards increased intercolonial cooperation and colonial independence from Britain gathered momentum during the early 1770s, Hewes assumed a place among the Whig leadership of the colony. On 4 Dec. 1773, the North Carolina Assembly in response to a Virginia resolution created a “Committee of Correspondence.” The committee consisted of Hewes, Speaker of the House John Harvey, Jr., Robert Howe, Cornelius Harnett, William Hooper, Richard Caswell, Edward Vail, John Ashe, and Samuel Johnston. In the spring of 1774, the committee approved a Massachusetts circular proposing that an intercolonial congress be convened in Philadelphia to formalize opposition to “British tyranny.” At an Assembly meeting held in August 1774, Hewes’s report of the Committee of Correspondence was approved and he, Caswell, and Hooper were selected as the colony’s delegates to the Continental Congress.

Hewes and Hooper arrived in Philadelphia on 14 September. Soon after taking his seat Hewes became acutely aware of the lack of unity among the delegates. On one extreme were the advocates of an uncompromising defense—by force if necessary—of American rights. The opposition argued for reconciliation with the Crown and were willing to recognize a wide latitude of Parliamentary authority over colonial affairs. The majority of the delegates, including those of North Carolina, found themselves somewhere between the two extremes. These moderate Whigs favored reconciliation with Britain, but they also stressed the need for guarantees against further infringements on American liberty. In succeeding weeks the moderates were able to control the tone of the debates and the actions of the Congress. After the Congress adjourned on October 26, 1774, Hewes remained in Philadelphia to renew old friendships and visit relatives. He also traveled to New York on business.

In late November, he returned to Edenton suffering from an “intermittent fever and ague.” In all probability Hewes had malaria, a disease common in Edenton due to the mosquito-infested swamps surrounding the town.

His mercantile firm, which had been reorganized with Robert Smith as “Hewes and Smith,” was valued at £20,000 in 1774; in addition, Hewes owned a shipyard on the bay south of Edenton. Business tax records for 1774 show that Hewes, along with his business partner and nephew, Nathaniel Allen, enslaved sixteen Black men and women. While attending to business affairs, he also served on Edenton’s Committee of Safety, which was responsible for enforcing the Continental Association in the Port of Roanoke.

By early 1775, the work of the moderate Whigs throughout the colonies for peaceful reconciliation with Britain had suffered massive setbacks. The British monarchy failed to consider the Declaration of Rights and Grievances and Parliament rejected the conciliatory proposals of Lords North and Chatham. A “state of rebellion” was declared in Massachusetts, and the British government ordered 10,000 additional troops to Boston. George III had chosen to answer colonial complaints with force. This somber realization was pressed home in late April when news of the battles of Lexington and Concord reached Hewes and the other delegates as they prepared to return to Philadelphia.

When the Continental Congress reconvened, Hewes began to urge North Carolina to strengthen its defenses. Hewes enlisted the aid of Presbyterian ministers in Philadelphia to counter Governor Martin‘s efforts among the colony’s Loyalists. First, a pamphlet was written for distribution to Highland Scot immigrants explaining the work of the Continental Congress. In November 1775, two of the ministers traveled south—with instructions drafted by Hewes—to further stem the tide of Loyalism in North Carolina.

Because of failing health and in order to attend the colony’s Third Provincial Congress, Hewes left Philadelphia six days before the August 1st adjournment of the Continental Congress. His stay in North Carolina, though brief, was marked by participation in the organization of a provincial government for the colony and in the authorization to raise the colony’s quota of Continental troops. On October 22nd, he rejoined his fellow delegates in Philadelphia. Among his committee assignments during this session, his service on the Naval Board proved to be the most exhaustive and most significant. From November 1775 to February 1776, he served as the board’s secretary, keeping its business records and conducting much of its voluminous correspondence. Possibly one of Hewes’s most noteworthy achievements on the board was to secure John Paul Jones’s first commission in the Continental Navy.

In 1776, King George III rejected the Olive Branch Petition, and proclaimed the colonies to be in a state of rebellion. This was closely followed by the Congress’s authorization for independent governments in each colony. In January 1776, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense publication was distributed in North Carolina. The following month, Governor Martin’s efforts among the Loyalists led to the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge–a Patriot victory. The final blow to moderate hopes came in March with news that the Crown closed colonial ports and placed the colonies under military rule. Hewes stated that “nothing is left now but to fight it out.” All hope of reconciliation had vanished and separation from England was now formally debated in the Continental Congress. Hewes’s pleas for instructions from North Carolina on the issue of independence were answered on April 12th by the Fourth Provincial Congress meeting at Halifax. The colony’s delegates were told “to concur with the delegates of the other colonies in declaring Independency.” On June 7th, Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee introduced the long-awaited resolution, which was approved in final form on 4 July 1776.

Hewes’s attitude from March to July 1776 is clear from his correspondence—he supported independence. In March 1776, Hewes became a revolutionary—albeit a reluctant one—but a revolutionary just the same.

Early in August 1776, Hewes left Philadelphia for a much-needed “recess from Publick Employment.” For almost a year he had been at work in that city and, from March through July, he had carried the entire workload of the North Carolina delegation alone. His health, already poor, by August had deteriorated to a dangerous degree. He complained of continual headaches, high fevers, and fading vision.

His hoped-for rest had to be postponed, for shortly after returning to Edenton he was elected the borough’s representative to the Fifth Provincial Congress. The main concern of this Congress, which met in Halifax during November-December 1776, was the drafting of a state constitution. This proved to be a most divisive process. The “Conservatives,” led by Samuel Johnston, James Iredell, and Hewes, supported a political system based on a strong executive and property qualifications for suffrage and officeholding. In vehement opposition were the “Radicals,” led by Willie Jones and Thomas Person, who argued for the establishment of a “direct democracy.” The constitution, as adopted on December 14th, improved the political position of the lower classes, but far from satisfied either faction. The debates over the document did produce one unfortunate result—an embittered and continuing division in the ranks of North Carolina Whigs.

Following the adjournment of the Provincial Congress, Hewes was able to rest in Edenton for a few months. Late in March 1777, his health had improved to the extent that he was planning to return to Philadelphia and the Continental Congress. That the state’s General Assembly would fail to appoint him was never considered. However, when the Assembly convened on April 7th, the previous Conservative-Radical factionalism reappeared, and the major point of contention became the reappointment of Joseph Hewes as delegate to the Continental Congress. Led by John Penn, the Radicals accused Hewes of plural office-holding, a violation under the new state constitution, and of reaping personal profit from his position as delegate. After many days of emotional debate, Hewes was bypassed and Penn was appointed as delegate. Although this defeat was a harsh one for Hewes, a more significant result may have been the withdrawal of many Conservatives, notably William Hooper, from politics.

Feeling that his reputation had been unjustly smeared, Hewes retired from public life, refusing in both 1777 and 1778 to stand for Edenton’s seat in the General Assembly. For two years he devoted his attention to regaining his health and supervising his extensive business affairs. The 1779 tax record shows that Hewes’s home was located on 120 acres of land and that he owned a plantation located in Tyrrell County. He also listed two town lots with “warehouses” and sixteen enslaved people as taxable property. At this time, the listing for his business included seven town lots, a plantation in Chowan county, fourteen enslaved people, and a “free mulatto” as taxable property.

Early in 1779, however, he acceded to popular demand and returned to the General Assembly. Soon after taking his seat, he allowed his name to be placed in nomination as a delegate to the Continental Congress. This time his election was not contested.

Soon after his arrival in Philadelphia, Hewes was appointed to the Treasury and Marine committees, two of the Congress’s most important and busiest standing committees. Within a month, he received two additional assignments. By the middle of August 1779, Hewes wrote that he again suffered from severe headaches and by late September he was so ill that he could not walk to Carpenter’s Hall. On October 29th, sensing that he could no longer fulfill his duties as delegate, Hewes submitted his resignation. Unable to travel, he remained in Philadelphia hoping that complete rest would restore his strength. However, his health was beyond repair and he died about two weeks later at age forty-nine.

When news of Hewes’s passing reached the Continental Congress, the delegates voted to attend the funeral as a body and proclaimed a one-month period of mourning. At 3:00 P.M. on November 11th, a gathering met at Hewes’s rooming house and escorted the body to Christ’s Church for burial. The Pennsylvania Packet, in its November 16th obituary, paid a tribute to Joseph Hewes: “His mind was constantly employed in the business of his exalted station until his health, much impaired by intense application, sunk beneath it.”

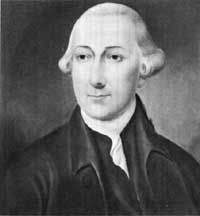

The only known likeness of Hewes is a 1 3/4-inch by 1 5/8-inch miniature painted on ivory by Charles Willson Peale in 1776. The oval portrait was framed as a lady’s broach and was a gift from Hewes to Helen Blair, the niece of Isabella Johnston. The miniature is now owned by the U.S. Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Md.”

Fun Facts: Three citizens from what is now the state of North Carolina signed the Declaration of Independence: They were Joseph Hewes, William Hooper and John Penn. Three other North Carolinians signed the Constitution: William Blount, Richard Dobbs Spaight and Hugh Williamson. Hewes and Williamson were residents of Edenton at the time.