By Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

Every family has legends. They are especially pervasive in the southeastern United States, where they have become part and parcel of the mystique of the “Old South”. Some legends are actually true. Some are based on truth, while many are the result of mistakes, faulty memory, or just the need to have a good family story to share. The goal for any historian is to be able to tell the difference.

One example of a southern family legend is set in Hertford County, North Carolina, which is located in the northeastern section of the state, abutting the Virginia state line. This legend was passed down by word of mouth by members of the Wynns and Newbern families and dates at least as far back as the 1880’s, a time when those first telling the tale would have had first hand knowledge. The legend is that the Wynns’ family home in the southern section of Hertford County, now called Wynnewood, as well as two nearby houses, were built by a slave carpenter named Drew Holloman. The earliest known family members to have shared this knowledge were sisters Mary Victoria Wynns, born June 15, 1889, and her older sister Eva Wynns. Both lived into their 90s, with Eva dying in 1976 at the age of 95. Their parents had shared the identity of the builder of their home with them. But once again, is there any basis in fact for this family legend?

Three questions need to be posed either to verify or disprove the story of slave builder Drew Holloman. The first question is obvious. Is there any record of the existence of an African American named Drew Holloman living in southern Hertford County during the period of construction of the three houses in question, roughly 1830 through 1860? Second, are there any records pointing to this individual’s involvement in carpentry or house joining, or of an elevated status enjoyed by this individual in the slave community of the period commiserate with that of a slave master builder? Lastly, are there any physical or decorative features that link these three houses, as well as neighboring houses, to the degree that they can be said to have been built by the same individual?

The answer to the first question is yes. There was an African American named Drew Holloman living in southern Hertford County during the period these three houses were constructed. The Hertford County census of 1870 lists Andrew Holloman as a 58 year-old farmer who was born in North Carolina. His wife, Teana, also a native North Carolinian, was born in 1814, so was two years younger than Andrew. Their children and household members are listed as Evelina, age 27, Amarfaret, 21, Jack, 18, Lawrence, 17, Martha, 15, William, 6, and William G, 3. The letter “m” is written beside the name of each family member in the column entitled “Color”, denoting each was identified as being of mixed race, or mulatto. They are listed as living in St John’s Township, which was and is located in southern and southwestern Hertford County.1 The houses in question are located in the same section of Hertford County.

Hertford County was founded in 1759. Benjamin Wynns, a member of a local, planter family and an ancestor of the Wynns family of Wynnewood, introduced the bill in the Colonial Assembly calling for the creation of Hertford County from portions of Bertie, Chowan, and Northampton Counties. The county seat was created on land donated by Wynns on the Chowan River. It was named Wynnston, later Winton, in his honor. The county maintained an agrarian based economy of small farms and mid-sized plantations. The largest plantations averaged 1000 to 1500 acres. By 1860, Hertford County’s population had grown to 9504, of which 3947 were white and 4445 were slaves. A substantial free black population also resided in Hertford County during the antebellum period. The 1860 census also lists 1112 individuals as free blacks. This category included a number of Native Americans. 2

A further examination of the county’s public records reveals evidence that answers the second question, although the search is hindered by the fact that Hertford County lost most of its records in two disastrous fires. The first took place in 1830, when a man named Wright Allen decided the best way to deal with his upcoming trial on forgery charges was to burn down the courthouse. The second fire came at the hands of Colonel Rush Hawkins during the 1862 invasion of eastern North Carolina by Union forces during the Civil War. Confederate forces fired upon Hawkin’s ships as they approached the wharf at Winton. Hawkins retreated down the Chowan River, only to return the following day to burn the entire town, save one house belonging to a man of known Union sympathies. Miraculously two will books survived both fires, but most all of the other county records were lost.

A few pre-1862 records pertaining to Hertford County survive in addition to the two will books. Also, some individuals rerecorded vital documents after 1865. But one of the two surviving will books holds an important clue to unraveling the mystery of this family legend. On September 19, 1853, George Holloman, a white planter, wrote his will. In it, he stated his desire that his daughter, Celia, “…in loan she have my servant Drew, wife Teiner and son Sam as part of her apportion which I loan her.” He divided other “negroes” among his four grandchildren, George Askew, William Jasper Askew, Susan Holloman, and Mary Lassiter.3 All four were the children of Celia and her late husband Seth Askew. This devise is important in three respects. First, it verifies that the Andrew Holloman listed in the 1870 Hertford County census is in fact the Drew Holloman in question, as his wife Teana is listed in both documents. Second, the fact that George Holloman specifically singles out these slaves, here called servants, for the use and support of his daughter, who was a widow at the time, demonstrates the special status of these individuals. Therefore, Drew must have had special talents and skills that made him more valuable than George Holloman’s other slaves. The third point is that “son Sam” was also a person of special significance to George Holloman. The 1870 Hertford County census lists at least three other children of Drew and Teana living in 1853 who were not included in this special devise to Celia.

Once again, the few Hertford County records that remain hold the clue to Drew and Sam’s special status. After the first few decades of the nineteenth century, census takers usually traveled from house to neighboring house and farm to neighboring farm, gathering data. So there is a high likelihood that individuals listed consecutively in census records lived beside or very near each other. The head of household listed immediately after Andrew Holloman in the 1870 Hertford County census is Samuel Holloman, undoubtedly Drew’s son. Samuel was born in 1836, so he was seventeen years of age at the time George Holloman wrote his will. More importantly, Samuel Holloman’s occupation is recorded. He was a carpenter.4

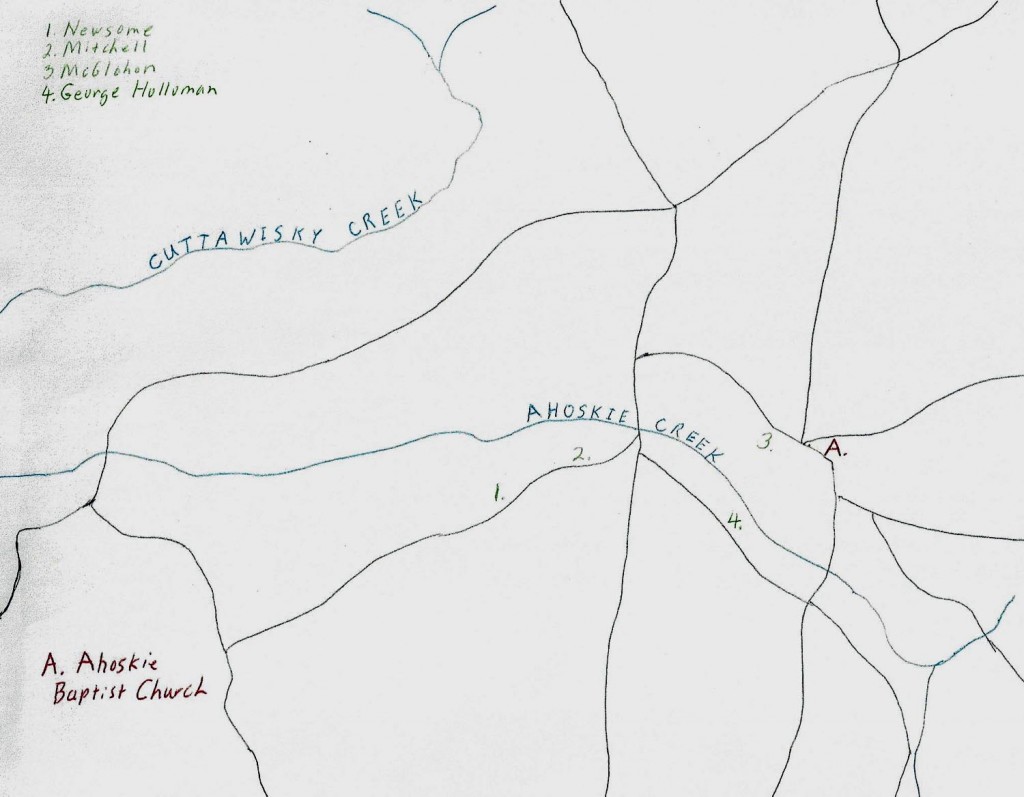

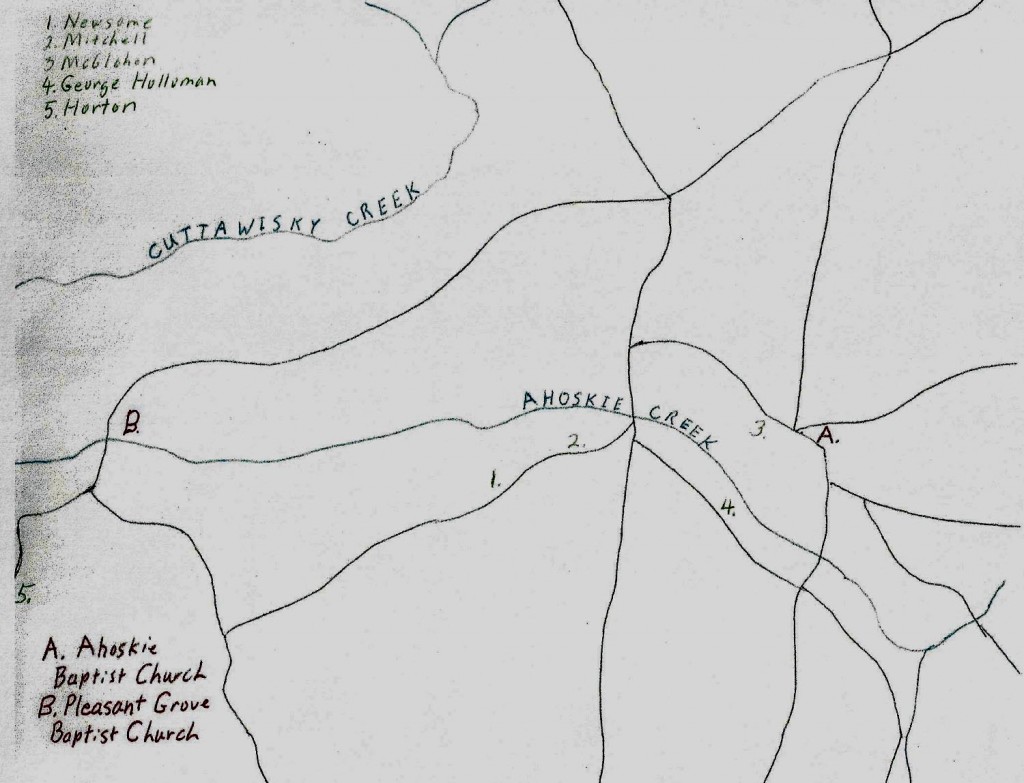

Adding further credence to the family legend of Drew Holloman’s status as a house builder, in addition to Sam’s occupation as a carpenter, is the fact that George Holloman was also a carpenter. George Holloman was born in Hertford County in 1782 and is credited, along with brothers Josiah, John, and Bryant, with building the Ahoskie Baptist Church in the early nineteenth century.5 A map drawn of Hertford and neighboring counties in 1863 under the supervision of Confederate engineer A. H. Campbell notes the location of the Ahoskie Baptist Church, labeled as “Ahosky Ch” on the map. Figure 1 illustrates the roads and creeks as they existed in southern Hertford County from 1830 to 1860. The location of the Ahoskie Baptist Church on Figure 1, as well as the locations on later maps of various houses being discussed throughout this article, are based on the 1863 Confederate map. The church’s location near the confluence of six roads illustrates its importance as a religious and community center of the surrounding countryside. The church therefore served as a focal point for the families for whom Drew Holloman constructed houses. Additionally, at the November 8, 1836 estate sale of neighbor Abisha Rawls, George purchased one carpenter’s adze, two gouges and chisels, one turner’s bench, one cross-cut saw, and one spoke shave.6 At this point, George Holloman was 54 years of age, so these tools may well have been intended for a younger man trained to build houses in his stead. Drew Holloman, 24 years of age in 1836, is a likely candidate to have received these tools. George Holloman undoubtedly trained Drew Holloman, creating the skills and marketability in Drew that led to his being singled out, with son Sam, in the will of 1853. Also, Drew’s listing as a mulatto in 1870 raises the inevitable question of a potentially closer relationship between George, or a member of George’s family, and Drew.

In addition to being a carpenter in his early years, George Holloman was also a small planter. By 1815, he owned 310 acres of land valued at $1000.00.7 His holdings had grown to 500 acres by 1850, along with numerous livestock including cattle, horses, and sheep. By 1850, his primary occupation, as listed in the 1850 census, was farming.8 Undoubtedly Drew was now in charge of the house joining aspect of George Holloman’s business enterprise and probably had been for some time.

Drew Holloman lived in that gray area of Southern antebellum society inhabited by the skilled slave artisan. His skills allowed him freedoms denied to other slaves, but he was still not free. He and other less skilled slaves were hired out by their owners to perform tasks for neighboring white planters and farmers. In Drew’s case, the task was building houses. The fees earned went mostly to the slave owner, but with a small portion to the slave. The more skilled the slave, the greater the amount of compensation earned by both slave and master.

A good example of the business relationship that existed between the white owner and the skilled slave artisan in antebellum Hertford County is found in the 1858 will of Luke McGlohon, a close neighbor of George Holloman. McGlohon was also a wealthy small planter who owned a number of slaves. Two of his slaves, both named Jack, were trained as sawyers. Sawyers were individuals who sawed logs into boards that could then be used in construction projects. McGlohon’s will stated “…that the two Jacks (sawyers) shall be allowed to saw as in my lifetime so long as they behave themselves and make their wages, however if they cease to do this I want them hired out in common stock, their hire divided as with the following negroes between my daughters…”. The next article in the will lists the names of six of McGlohon’s other slaves who were hired out as manual laborers, obviously with much more structure and less freedom than were allowed the two Jacks who were engaged as skilled laborers.9 So a slave capable of constructing houses and therefore with the ability to earn a substantial income for his master, must have been afforded a level of autonomy approaching that of a free individual. That applies, of course, only so long as they make their wages, “behave themselves” in the words of Luke McGlohon, and remain invisible, living between the world of the slave and the world of the slave owner.

One Hertford County record demonstrates Drew Holloman’s participation in, and mastery of, this little studied system of the acquisition of wealth by skilled slave artisans in the antebellum South. It is found in the estate records of James Newsome, a wealthy planter and neighbor of George Holloman. James Newsome’s home, which passed to the Wynns family through marriage, is in fact the Wynns family home now called Wynnewood, and is the main subject of the Drew Holloman legend. The Newsome estate was settled in 1867. The Civil War had just ended, and most of the newly freed slaves were struggling to survive without appreciable assets in their new world of freedom. Yet the estate of James Newsome noted a debt owed to Drew Holloman for the hire of a horse.10 Therefore, Drew Holloman endured slavery and survived the devastation of war with not only the ability to provide for himself and his family, but with the additional resources to rent a horse to a former slave owner.

Despite the loss of most Hertford County records as a result of fire and war, the first two questions posed at the beginning of this article can be answered in the affirmative. Records document the existence of an African American named Drew Holloman living in southern Hertford County in the same area as the location of the three houses in question. Records further reveal that based on his owner’s trade, his son’s trade, his ownership of property at a time when most newly freed slaves were destitute, and his special status as recorded in the will of his owner, there is every reason to believe that Drew Holloman was trained as a carpenter and house joiner, just as stated in the family legend.

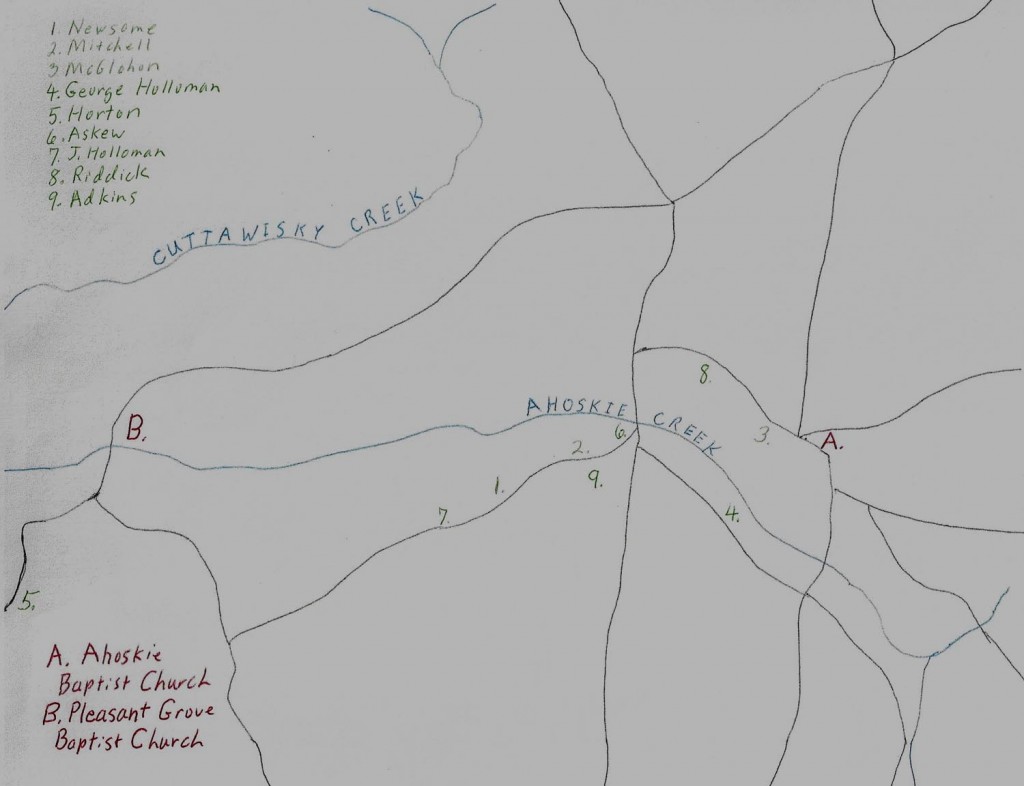

The third and final question to be answered to prove or disprove the legend of Drew Holloman involves an examination of the three houses in question for construction and decorative features to demonstrate whether the same individual built them. Figure 2 illustrates the locations of the three houses purportedly built by Drew Holloman. They are the James Newsome house, now called Wynnewood, the William W. Mitchell house, and the Luke McGlohon house. George Holloman’s home, and therefore the home of Drew Holloman until 1865, is denoted on the Confederate map as “Mrs. Askew”. George Holloman’s widowed daughter, Celia Askew, had inherited his property upon his death in 1853. There are no records or photographs that reveal the appearance of the George Holloman house.

The house now known as Wynnewood appears to have been built in the 1830’s (Fig. 3, Newsome house). It was constructed for James Newsome, the same individual whose estate was indebted in 1867 to Drew Holloman for the use of a horse. Newsome was born in 1800. By 1850, he had acquired 1180 acres of land in south central Hertford County, 150 of which were improved. This land was valued at $1700.00, while his livestock was valued at an additional $1000.00.11 By 1860, the value of Newsome’s land had risen to $3500.00, with his personal property valued at $14067.00.12

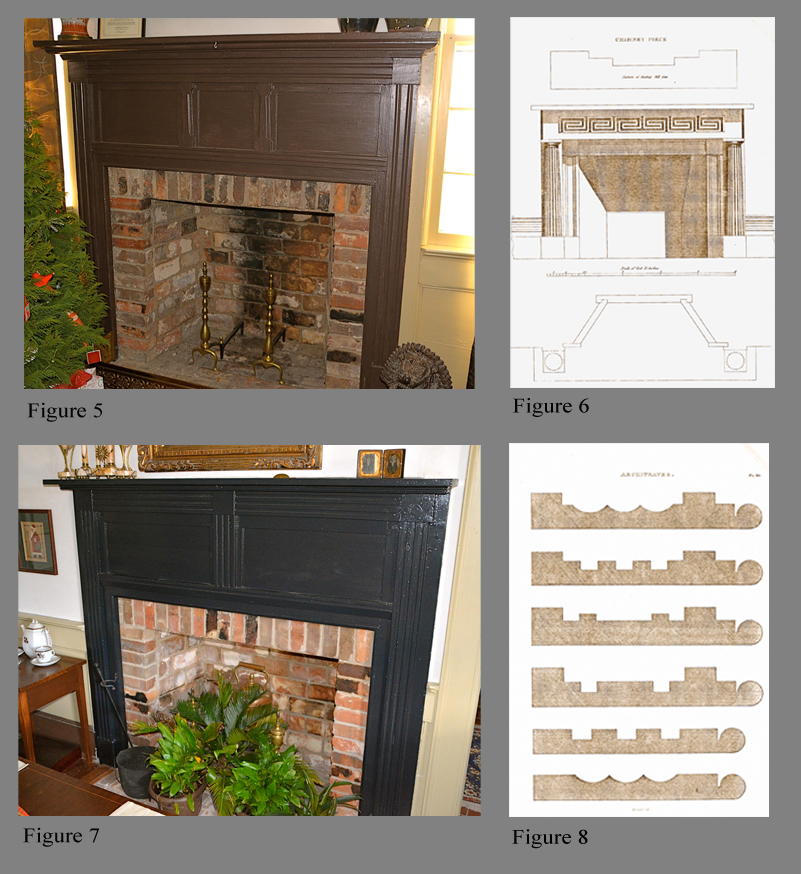

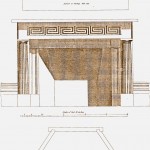

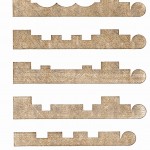

The James Newsome house appears to be the earliest of the houses mentioned in the family legend. Although it was extensively remodeled in the 1970’s, it retains much of its original interior woodwork as well as some original beaded siding now reused on its west face. It is a two-story, three-bay hall and parlor structure, with a full-width rear shed. It originally had a full-width front porch. A family photograph taken in front of the house when it was in the Wynns family’s possession shows its original porch and window configuration (Fig. 4, Family photograph featuring Newsome house). The house retains its original wainscot in its front two rooms featuring wide, unadorned baseboards and chair rails, although now with added moldings. The mantelpieces, however, are extravagant vernacular examples incorporating architectural elements take directly from Asher Benjamin’s The Practical House Carpenter (PHC), which was first published in 1830. The hall mantelpiece’s frieze is composed of three flat panels separated by two small Doric pilasters (Fig. 5, Mantelpiece of Fig. 3). Double fluted architraves frame the sides of the fireplace and are capped by unadorned corner blocks. This molding was probably derived from an interpretation of Plate 51 in Benjamin’s work, although the plate illustrates molding of a different form (Fig. 6, Plate 51 in PHC). The same fluted molding connects the mantelpiece’s corner blocks, separating the frieze from the mantle shelf. Although this fluted molding with corner blocks is usually found as trim around window and door openings, it is illustrated in Plate 51 in a mantelpiece. In Plate 51, however, it is used to frame the fireplace rather than the fireplace and the mantelpiece frieze. The parlor mantelpiece employs a different molding to frame the fireplace and mantelpiece frieze, as well as to separate the frieze’s two panels (Fig. 7, Mantelpiece of Fig. 3). This molding matches the fifth molding found in Plate 46 in The Practical House Carpenter (Fig. 8, Plate 46 in PHC). Several of the house’s original six panel, flat-paneled doors remain on the first floor.

An enclosed winder staircase leads to two rooms on the second floor. Usually the walls on both sides of an enclosed staircase continue to the second-floor ceiling, creating two enclosed second-floor rooms, each with a door at the top of the staircase. In the Newsome house, however, only one wall continues upward to create an enclosed room. The second room was actually an open loft, separated from the stair well by a balustrade. An examination of the attic clearly reveals evidence that a later wall was added which formed the second enclosed bedroom and a small second-floor passage. The mantelpiece in what was the loft contains a two paneled frieze, with a board containing an X separating the panels (Fig. 9, Mantelpiece of Fig. 3). Double-fluted molding meeting at corner blocks frames the fireplace and mantelpiece frieze. The mantelpiece located in the originally enclosed, proper-left second-floor room has been removed from the house. Wainscot with wide unadorned baseboards and unmolded chair rails remains on the second floor of the Newsome house (Fig. 10, Second-floor wainscot of Fig. 3). The current moldings are later additions.

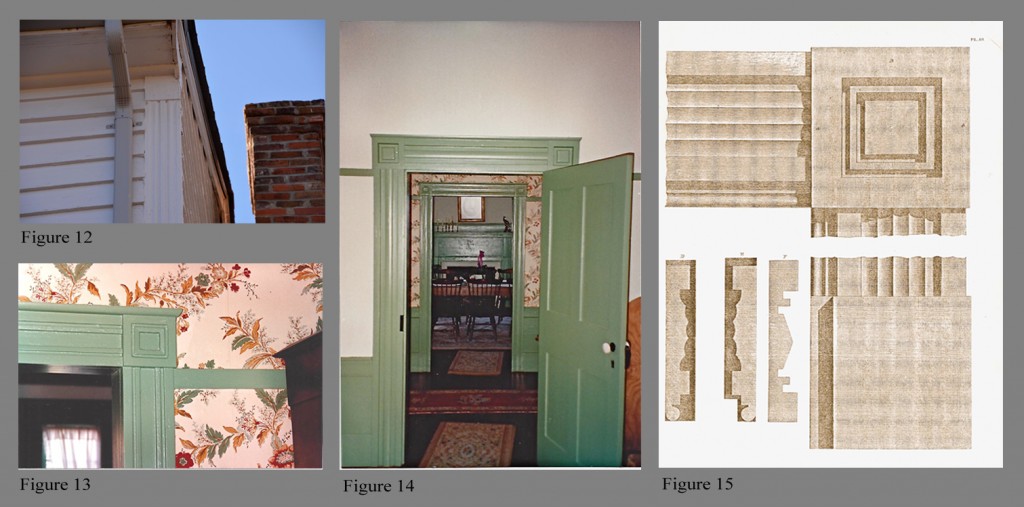

The town of Ahoskie, incorporated in 1893, now surrounds the second house in question. When it was built for Luke McGlohon in the late 1840’s or early 1850’s, it was in a rural setting less that one-half mile from the Ahoskie Baptist Church (See Fig. 2). The McGlohon house is a two-story, five-bay structure with a central front porch covering the front door and a window on either side (Fig. 11, McGlohon house). It has a well-formed corner board on each end of the front facade, capped with an unadorned corner block (Fig. 12, Exterior molding of Fig. 11). The central passage, as well as the room on either side, contain wainscot with wide, unmolded baseboards and simple chair rails and top rails. Picture slips, which are horizontal strips used for hanging pictures, are also found in the central passage. Please note that depending upon height above the floor and location, these horizontal strips, when fitted with nails, hooks, and/or pegs, can serve equally well as cloak rails for hanging garments. For consistency in this article, we will continue to refer to these horizontal strips as picture slips. The architraves of the central passage door openings are copied from the third molding found in Plate 46 of The Practical House Carpenter (Fig. 13, Passage molding and corner block of Fig. 11) (See Fig. 8). They include square corner blocks with square moldings in their centers (See Fig. 13). Corner blocks with raised square central elements are used in the proper-left first-floor room (Fig. 14, Molding and corner block of Fig. 11). Both styles of corner blocks are interpretations of a corner block illustrated in Plate 48 in Benjamin’s work (Fig. 15, Plate 48 of PHC). The architrave surrounding the door opening in the left room is derived from the fourth molding illustrated in Plate 47 in Benjamin’s book (Fig. 16, Plate 47 of PHC) (See Fig. 14). Original brackets that once supported square curtain rods remain in both first-floor rooms (Fig. 17, Curtain bracket of Fig. 11). The first-floor mantelpieces are less ornate than those found in the Newsome house. The mantelpiece in the proper-right first-floor room contains flat pilasters that frame the fireplace and the mantelpiece’s frieze (Fig. 18, Mantelpiece of Fig. 11). The pilasters of the mantelpiece in the proper-left first-floor room contain half-round columns, while the mantelpiece frieze contains a vernacular Greek key design (Fig. 19, Mantelpiece of Fig. 11). A picture slip is used above this mantelpiece.

A winder staircase leads to the second floor. An open balustrade, similar to that found in the Newsome house, creates a central second-floor passage with the rear of the passage sectioned off as a small room. The newel post of this second-floor balustrade tapers at the top and is capped with a small block (Fig. 20, Newel post of Fig. 11). The McGlohon house contains an enclosed bedroom on either side of the second-floor passage. Each bedroom contains a plain, vernacular mantelpiece, as well as unadorned, wide baseboards and plain chair rails (Fig. 21, Mantelpiece of Fig. 11) (Fig. 22, Mantelpiece of Fig. 11). The second-floor bedrooms also have picture slips above the mantelpieces, while an additional picture slip is found between two windows in the second-floor central passage.

The third of the three houses referred to in the family legend of house joiner Drew Holloman was probably built between the completion dates of the previous two houses. Like the McGlohon house, it is a two-story, five-bay house with a central front porch which here only shelters the front door (Fig. 23, Mitchell house) (See Fig. 2). An original two-story ell extends behind the proper-left front rooms. The house was built for William W. Mitchell, whose plantation adjoined the northern edge of the Newsome property. Mitchell was born on December 20, 1810. By 1860, he had acquired 1000 acres valued at $6000.00, in addition to personal property worth $39026.00.13 Mitchell was chairman of the County Court from 1861 until 1866 and served Hertford County as a Justice of the Peace for 25 years. He married three times, first in 1832, next in 1834, and lastly in 1845.14 The house was probably built during his second marriage or for his third wife in 1845.

The front door opens into a central passage that is flanked by a room on either side. The mantelpiece in the proper-right first-floor room matches the parlor mantelpiece in the Newsome house, although this mantelpiece employs molding similar to that found in the McGlohon house’s proper-left first-floor room (Fig. 24, Mantelpiece of Fig. 23) (See Figs. 7 and 14). The door and window architraves in this room are taken from molding F in Plate 48 in Benjamin’s book, while the room’s corner blocks exactly match the corner blocks illustrated in the same plate (Fig. 25, Molding and corner block of Fig. 23) (See Fig. 15). The mantelpiece in the Mitchell house’s proper-left first-floor room contains a half-round column in each of its pilasters that is very similar to those in the McGlohon house’s more ornate mantelpiece (Fig. 26, Mantelpiece of Fig. 23) (See Fig. 19). The mantelpiece in the first-floor ell matches that found in the proper-right first-floor room. Picture slips are found in the Mitchell house’s first-floor central passage, over the first-floor mantelpieces, and on other first-floor walls.

The staircase rises from a stair passage located in the front portion of the first-floor ell. The second-floor balustrade contains a tapered newel post with cap that matches that found in the McGlohon house (Fig. 27, Newel post of Fig. 23) (See Fig. 20). The mantelpieces in all of the second-floor rooms contain the same double-fluted molding in the same locations as found on the Newsome house hall mantelpiece (Fig. 28, Mantelpiece of Fig. 23) (Fig. 29, Mantelpiece of Fig. 23) (See Fig. 5). Second-floor door and window architraves contain this same double-fluted molding. The second-floor rooms also retain their original grain painting. A wardrobe, supposedly built by a slave on the property, remains on the second floor of the Mitchell house. That slave was probably Drew Holloman. (Fig. 30, Wardrobe in Fig. 23)

While an examination of the previous three houses clearly shows them to have been built by the same individual, and can now be attributed to Drew Holloman, their comparison to a fourth house makes their relationship to each other even more obvious. The first three houses were all constructed in the farming community that developed in south-central Hertford County around the Ahoskie Baptist Church, which was built by Drew Holloman’s owner George Holloman and his brothers. The fourth house, however, was built approximately eight miles to the west for Jordan J. Horton, shortly after his purchase of the property from the Powell family in 1852 (Fig. 31, Horton house). A branch of the Ahoskie Baptist Church, Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, was organized in 1837 within two miles of the property purchased by Horton (Fig. 32, Map of southern Hertford County). George Holloman was a very active member of the Ahoskie Baptist Church, which may explain how Horton became familiar with Drew Holloman’s work. From the appearance of woodwork in the present Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, it was probably constructed around 1850. Its interior door and window architraves are closely related to the molding used in the Mitchell house’s proper-right first-floor room and appear to be by the same hand. (Fig. 33, Molding and corner block of Pleasant Grove Baptist Church) (See Fig. 25). So it is likely that the most important builder in the area surrounding the parent church was involved in this church’s construction.

J. J. Horton was a prominent planter in the southwest corner of Hertford County. He represented the county in the North Carolina House of Representatives from 1879 through 1881.15 In 1860, he owned 1041 acres valued at $7500.00.16 Upon his purchase of the Powell property, Horton added a large two story section with a double portico front porch to an existing house. William Seay constructed this original house for Cadar Powell around 1798. The Powell house and property had passed by inheritance to Cadar’s son, Jesse Robert Powell, who sold it to Horton. The Powell house originally faced west, fronting a main trade route connecting Winton, North Carolina, on the Chowan River to the north, and the Roxobel and Norfleet’s Ferry area on the Roanoke River and points south. Horton had the Powell house turned 90 degrees, with its original front now facing south. The exterior parlor wall and chimney were removed, with the parlor now serving as the back passage of the new Horton house. This new front section of the Horton house was built by Drew Holloman and contains a large central passage flanked by a room on either side (Fig. 34, First-floor passage of Fig. 31). The same floor plan was used on the second floor. The first-floor central passage contains two levels of picture slips, while the second-floor central passage contains a single-tier picture slip. The first-floor rooms are twelve feet high, while the second-floor rooms have eleven-foot ceilings. A large arch was constructed in the rear of the first-floor passage where it joins the former parlor of the original Powell house. The original grain painting of the arch and doors has been recreated.

The exterior of Horton’s new front addition contains molded corner boards exactly matching the corner boards of the McGlohon house (Fig. 35, Exterior molding of Fig. 31) (See Fig. 12). This same molding is used on the Horton addition’s exterior door and window architraves, again matching the McGlohon house. The Horton addition’s first-floor interior architraves also match those in corresponding rooms in the McGlohon house. The McGlohon house was probably constructed first. The fact that the Horton addition was built eight miles away may explain why Drew Holloman felt comfortable duplicating the woodwork he created for Luke McGlohon. Even the brackets used to support window hangings were copied (Fig. 36, Curtain brackets of Fig. 31) (See Fig. 17). The scale of the Horton addition, however, is much larger, with windowpanes measuring twelve by fourteen inches set in nine over nine sash on the first floor and nine over six sash on the second floor. During renovations in the 1980’s, an original Powell house front porch post was found cut in half and used as corner braces in the first-floor passage of the Horton addition.

The addition’s proper-left first-floor room originally served as the dining room, and it retains L-shaped metal bars set in the room’s studs for hanging large paintings. Extra bars were inserted in the corners of the room closest to the central passage to allow pictures to be centered with or without corner cupboards in those corners. While the other two first-floor rooms contain full wainscot matching that found in the McGlohon house, this room contains only a wide baseboard with panels under the windows. The mantelpiece in this room, as well as in the second-floor room on the opposite end of the addition, had been removed before the house was restored. The mantelpiece in the proper-right first-floor room remains in place and matches the plainer mantelpiece in the corresponding room on the first floor of the McGlohon house (Fig. 37, Mantelpiece of Fig. 31) (See Fig. 18). The missing first-floor mantelpiece probably matched the more ornate mantelpiece in the McGlohon house’s first floor and could explain why it was removed. The proper-left first-floor room also contains the most unusual architectural feature found in the Horton addition. A nine-panel overdoor surmounts the room’s doorway (Fig. 38, Overdoor in Fig. 31). Its panels are separated by unadorned square blocks and molding related to that found on the parlor mantel of the Newsome house (See Fig. 7). The Newsome house version of this molding is used around the door openings in the Horton addition’s second-floor passage.

The proper-right second-floor room of Horton’s 1852 addition contains door and window architraves employing the same double-fluted molding found in the Newsome house hall mantelpiece as well as the second-floor mantelpieces found in the Mitchell house (Fig. 39, Molding and corner block of Fig. 31) (See Figs. 5, 28, and 29). It also matches the molding found on the second-floor door and window architraves in the McGlohon house (See Fig. 22). The proper-left second-floor room’s mantelpiece matches the remaining original first-floor mantelpiece. This room’s door and window architraves are closely related to those found in the Mitchell house’s proper-right first-floor room and match those found in Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, except here a single flute is placed on the central element of the molding. (Fig. 40, Molding and corner block of Fig. 31) (See Figs. 25 and 33). Wide unadorned baseboards and unmolded chair rails are found in the second-floor rooms of the Horton addition. The four-paneled doors of this section of the house contain molding found on the Newsome house mantelpieces as well as in Pleasant Grove Baptist Church.

A comparison of the previously discussed houses to four other examples in the area around the Ahoskie Baptist Church offers evidence that Drew Holloman also constructed them (Fig. 41, Map of southern Hertford County). One is located just north of and adjoining the Mitchell plantation. It was built for George Askew, grandson and namesake of Drew Holloman’s owner, George Holloman (Fig. 42, Askew house) (See Fig. 41). It is a two-story hall and parlor house with a full-width front porch and a full-width rear shed. What remains of the mantelpiece in the parlor matches the less ornate first-floor mantelpiece in the McGlohon house and the surviving first-floor mantelpiece in the Horton addition (Fig. 43, Mantelpiece of Fig. 42) (See Figs. 18 and 37). The hall mantelpiece contains half-round columns matching the more ornate first-floor mantelpiece in the McGlohon house (Fig. 44, Mantelpiece of Fig. 42) (See Fig. 19). Both of the Askew house’s first-floor rooms contain wainscot with unadorned wide baseboards and unmolded chair rails matching those found in the first-floor passage and proper-right room of the Horton addition, as well as the wainscot in the McGlohon house’s first-floor rooms. The Askew house’s second-floor mantelpieces are very similar to its less-ornate first-floor mantelpiece, though here with thin double pilasters rather than thicker single pilasters (Fig. 45, Mantelpiece of Fig. 42) (See Fig. 43).

A coastal cottage built for James Holloman, a cousin of George Holloman, also can be attributed to Drew Holloman (Fig. 46, James Holloman house) (See Fig. 41). Its front wall contains original beaded siding with cut nails and probably dates to the 1830s, around the time the Newsome house was constructed. The James Holloman property is located just south of the Newsome tract and may have adjoined it at one time. The house consists of a hall and parlor with what appears to be a later full-width shed addition. Its loft retains its original plaster.

An extravagant mantelpiece matching that found in the Newsome house parlor remains in the parlor of the James Holloman house (Fig. 47, Mantelpiece of Fig. 46) (See Fig. 7). The hall mantelpiece matches the second-floor mantelpieces in the George Askew house (Fig. 48, Mantelpiece of Fig. 46) (See Fig. 45). The interior and exterior window casings in the original section of the house contain two-part architraves without corner blocks. The window casings on the shed addition, however, contain corner blocks.

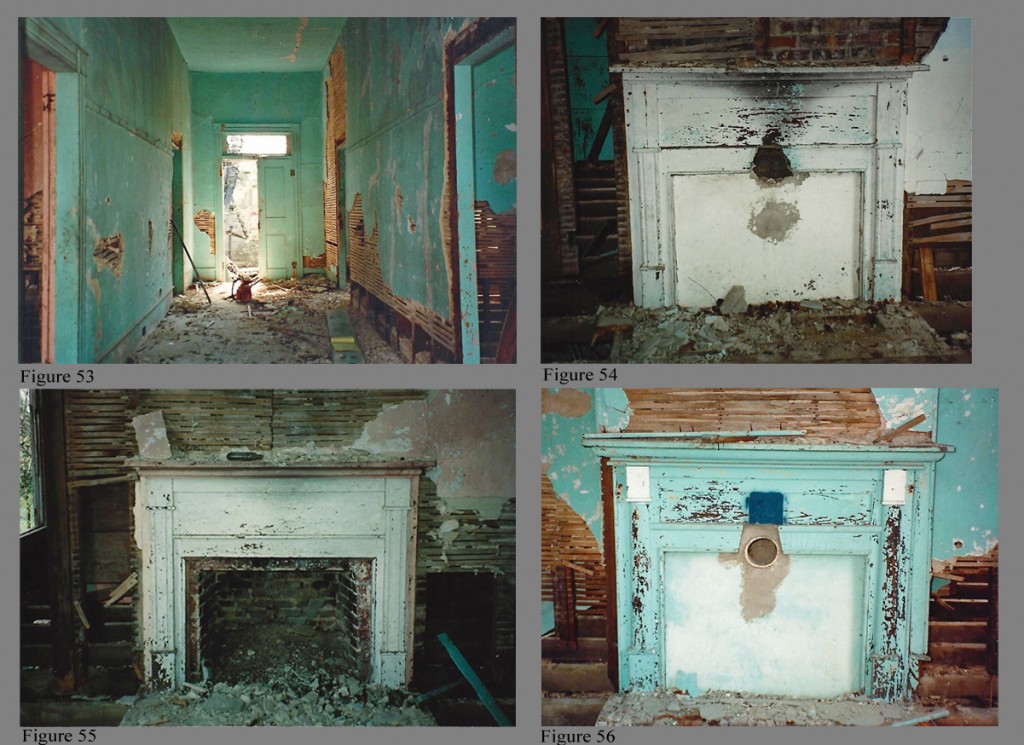

A large single-story house located one mile northeast of the George Askew property was built for planter James A. Riddick (Fig. 49, Riddick house) (See Fig. 41). In 1860, Riddick owned 792 acres valued at $4000.00.17 The house was probably constructed in the late 1850’s or early 1860’s, and is the latest of the houses attributed to Drew Holloman. The house was destroyed in the 1980’s, but fortunately photographs of the house were taken as it was being disassembled. The house consisted of a 32-foot central passage flanked by two rooms on either side. A four-pane transom was located at each end of the central passage to provide illumination (Fig. 50, Transom of Fig. 49). An interior chimney was located between the flanking rooms on either side of the central passage. The house’s twelve-foot ceilings matched those found on the first floor of the Horton addition. The interior door and window molding of the proper-right front room match the molding found in the first-floor room of the Horton addition containing the overdoor (Fig. 51, Molding of Fig. 49) (See Fig. 38). This room also contained an overdoor, here with six panels rather than the nine panels in the Horton addition example (Fig. 52, Overdoor of Fig. 49) (See Fig. 38).

This unusual North Carolina feature, based on overmantels found in earlier northeastern North Carolina houses, was also found in the Adkin’s house, originally located across the road from the Mitchell house (See Fig. 41). N.B. Adkins was a 32-year-old middling planter in 1860 who owned real estate valued at $300.00 and personal property valued at $490.00.18 Like the Riddick house, the Adkins house was a single-story house with a hipped roof. Its front door opened into a short central passage with a fully paneled rear wall. This paneling matched that of an overdoor located in the proper-right front room. A door in the paneled wall at the rear of the entry passage led to a continuation of the central passage. Two rooms were located on either side of the two-part central passage. The Adkins house had two exterior chimneys serving its front two rooms. Unfortunately, the house was destroyed before photographs could be taken to document it.

The rooms in the Riddick house had wide, unadorned baseboards with no wainscot or chair rails. The central passage had a single picture slip continuing around the entire room (Fig. 53, Passage of Fig. 49). Flat panels were placed under its large windows in the interior of the house, matching the proper-left first-floor room in the Horton addition. All interior door and window architraves, except the central passage and proper-right front room, contained double-fluted molding. This was the most common molding used by Drew Holloman and was used in most of the houses he built, especially after 1840. One of the Riddick house’s mantelpieces matched the mantelpiece found on the second floor of the Askew house, as well as in the hall of the James Holloman house (Fig. 54, Mantelpiece of Fig. 49) (See Figs. 45 and 48). Another Riddick house mantelpiece matched a second-floor mantelpiece in the McGlohon house (Fig. 55, Mantelpiece of Fig. 49) (See Fig. 22). A third was also very similar to the McGlohon mantelpiece, but here with half-round columns (Fig. 56, Mantelpiece of Fig. 49).

Drew Holloman is one of only a handful of African American slave house joiners to be documented in North Carolina. He occupied that small stratum of Southern antebellum society between the world of slavery and the world of freedom. Free black artisans such as house joiner and cabinetmaker, Thomas Day of Milton, and cabinetmaker, Henry Evans of Hillsborough, are more easily identified in the written records of the period. Drew Holloman’s story, like so many in the African American community, was passed down by word of mouth. However, this family legend was preserved in the family of former slave owners, rather than former slaves. So, despite the loss of so many of Hertford County’s early records, ample evidence remains in the written record to offer proof of this oral family history. The houses themselves speak most loudly to the skill and fortitude of a man who could create them as he survived in a world of slavery and inequality.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Rachel Newbern Pitman. Rawel, as she was affectionately known to family and friends, was a great lover of history, genealogy, and Southern decorative arts and architecture. It is through her efforts that the story of Drew Holloman was preserved and passed down to a time it could be documented.

- Fig 1

- Fig 2

- Fig 3

- Fig 4

- Fig 5

- Fig 6

- Fig 7

- Fig 8

- Fig 9

- Fig 10

- Fig 11

- Fig 12

- Fig 13

- Fig 14

- Fig 15

- Fig 16

- Fig 17

- Fig 18

- Fig 19

- Fig 20

- Fig 21

- Fig 22

- Fig 23

- Fig 24

- Fig 25

- Fig 26

- Fig 27

- Fig 28

- Fig 29

- Fig 30

- Fig 31

- Fig 32

- Fig 33

- Fig 34

- Fig 35

- Fig 36

- Fig 37

- Fig 38

- Fig 39

- Fig 40

- Fig 41

- Fig 42

- Fig 43

- Fig 44

- Fig 45

- Fig 46

- Fig 47

- Fig 48

- Fig 49

- Fig 50

- Fig 51

- Fig 52

- Fig 53

- Fig 54

- Fig 55

- Fig 56

Published on: Feb 5, 2014 @ 3:19

Endnotes

- Hertford County Census, 1870.

- Hertford County Census, 1860.

- Hertford County Will Book A, p. 356.

- Hertford County Census, 1870.

- J. Roy Parker, The Ahoskie Era of Hertford County, Parker Brothers, Inc., Ahoskie, NC, 1939, p. 391.

- Raymond Parker Fouts, Record of Accounts, Inventories and Sales of Estates, Hertford County, NC: 1835-1837. Vol. III, Gen Rec Books, Cocoa, FL, 1992, p. 55.

- Hertford County Tax List, 1815.

- Hertford County Census, 1850.

- Hertford County Will Book B, p. 9.

- Hertford County Record of Accounts, 1868-1873, p. 273.

- Hertford County Census, 1850.

- Hertford County Census, 1860.

- Ibid.

- Benjamin B. Winborne, The Colonial and State History of Hertford County, North Carolina, Genealogica Publishing Co., Inc., 1976, pp. 228 and 236.

- Ibid, p. 323.

- Hertford County Census, 1860.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.