By Jim Melchor and Tom Newbern

From the dawn of mankind, humans have needed blades for hunting, chopping, cutting, and fighting. In this article, we will focus on the evolution of blades in what is now Virginia and North Carolina from pre-historic times into the early nineteenth century. 1

The length of time humans have inhabited North America is still in question. Estimates range upward in the tens of thousands of years with no clear resolution is sight. However, we do know humans have lived in Virginia and North Carolina for at least the past 12,000 years. There is clear evidence of this in the plethora of artifacts left by these people, primarily stone tools including, but not limited to, projectile points, knives, scrapers, choppers, axes, and the stone waste (reduction flakes and broken rocks) resulting from the manufacture of these tools.

In Virginia and North Carolina, as elsewhere in eastern North America, there are basically three, recognized, distinct periods of early man, Paleo-Indian (circa 12,000 years BP and before), Archaic (circa 10,000 years BP to circa 3,000 years BP), and Woodland (circa 3,000 years BP to contact with Europeans). Some overlap from period to period did occur, and there were developmental stages within each period. Full discussions of these periods are, and have been, argued in detail in the print media and online.

The Paleo-Indian people consisted primarily of small family groups of nomadic hunters who followed and killed large and small animals for their primary subsistence. However, they undoubtedly utilized other food resources they encountered. Archaic people were primarily larger groups of migratory hunters and gatherers whose subsistence depended both on the killing of animals and on the gathering of other wild edibles such as shellfish, fish, nuts, berries, fruits, vegetables, roots, etc. The Woodland people also hunted and gathered, but they were primarily farmers living in larger settlements and even “cities”. These are the people the first European explorers and settlers encountered in the new world and called “Indians” in the mistaken belief that they had discovered the East Indies. Unlike elsewhere in the world where early man transitioned from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, these Native Americans, encountered by the first Europeans, were still in the Stone Age.

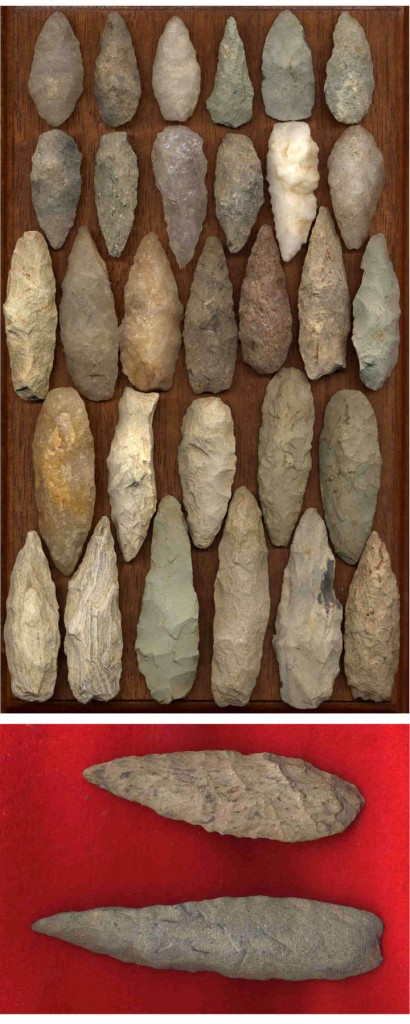

The most recognizable tool of the Paleo-Indians in Virginia and North Carolina is the finely made, fluted, lanceolate point or blade (Fig. 1, Four fluted points found in eastern Virginia, top left – Surry County, top right – City of Williamsburg, center – Brunswick County, and bottom – Williamson Paleo-Indian Site, Dinwiddie County). This type of fluted point resembles similar points found near Clovis, New Mexico, and the term, Clovis point, has been generically applied to this form. Clovis points most likely were used as spear points and hafted knives. However, fine points are not the only Paleo-Indian artifacts encountered in Virginia and North Carolina. Indeed, more mundane stone tools are also found on Paleo-Indian sites such as the scraper and preform in Figure 2 (Fig. 2, Scraper on left and preform on right, both found on the Williamson Paleo-Indian Site, Dinwiddie County). Scrapers were used for scraping flesh and hair from hides as well as for scraping wood, bone, etc. Preforms are larger pieces of suitable stone that were reduced in size for easier transport. They could be used as a scraper or chopper, as is, or flaked into a projectile point, knife, or other tool as needed, the prehistoric equivalent of a Swiss army knife. The Williamson Paleo-Indian Site and the adjoining Ampy Farm are literally covered in stone artifacts and debris, every piece of which has been worked to some extent by early man. The readily recognizable, bluish, stone material encountered here is known as Little Cattail Creek chalcedony, a cryptocrystalline form of quartz. Archaeologist Floyd Painter coined the name. 2 The actual source of the stone on this extensive workshop site has not been found, but it probably was an outcrop in one of the deep ravines on the property that was mined out by the Paleo-Indians occupying the site. Because of the relatively small population of Paleo-Indians in Virginia and North Carolina, their artifacts are quite rare compared with those of the subsequent two cultures. Though heavily picked for many years, the Williamson Paleo-Indian Site remains an important research location for those studying early man. A major collection of points and other tools from the Williamson Paleo-Indian site resides at the College of William and Mary.

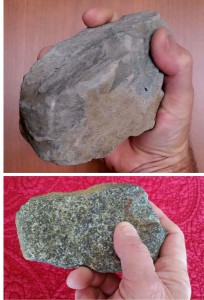

As a basic overview, three techniques were incorporated in the manufacture of stone tools of the Paleo-Indians; percussion flaking, pressure flaking, and grinding. Percussion flaking involves the striking of a stone workpiece to remove large chips or flakes from the workpiece for further shaping, to reduce the size of the workpiece, or to refine the shape of the workpiece. The striking implement can be another stone (hammer stone) or heavy baton of antler or wood (Fig. 3, Hammer stone, workpieces, flakes). Pressure flaking involves precisely removing small flakes in the process of shaping a larger flake into a finished tool. Pressure is applied to the edge of a flake with a pointed antler, bone, or possibly wood tool (Fig. 4, Deer antler, flakes being worked, and small flakes removed). Fluted points required careful pressure flaking in shaping the point overall. Also, pressure flaking was incorporated in preparing a blade for percussion removal of the long flakes of the flutes. The arched base and sides of a fluted point near its base were ground smooth with an abrasive stone to prevent sharp edges from cutting the binding material holding the blade to its haft. 3

While the above explanation of the flaking process might sound simplistic, nothing could be further from the case. Producing stone blades, most especially Clovis points, took considerable skill, precision, and time of an accomplished knapper or stone worker, even in the production of basic tools. Also, stone material was carefully selected for its flaking characteristics (workability) and often for its aesthetics. The survival of the Paleo-Indians depended on their blades. It should be noted here that once a blade was produced, it would have been reworked as necessary as it sustained damage until such time it was lost or no longer useful. As can be seen in Figure 1, the top two fluted points have been substantially reduced in length through reshaping as their tips were damaged in use. Also seen in Figure 1, the tip of the point in the center has been reshaped into a scraper, probably as a result of damage to the original pointed tip.

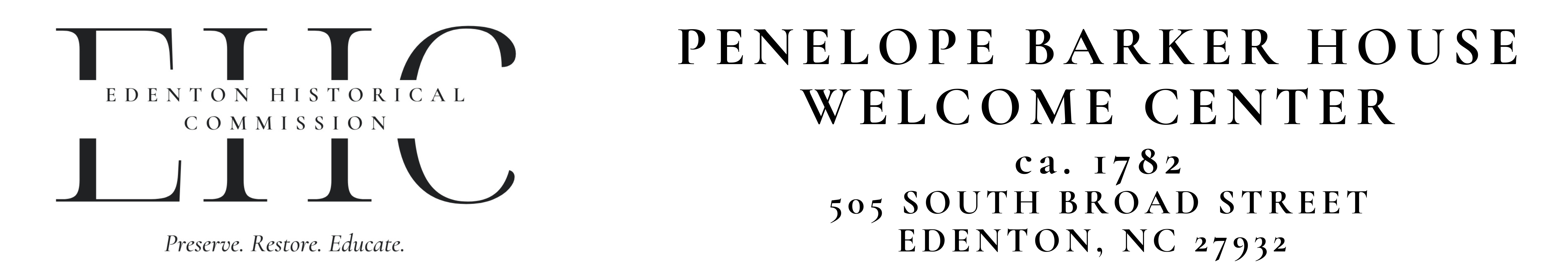

Archaic artifacts are plentiful due to the longevity of the period, the vastly increased size of the population, and the spatial distribution of the population. In fact, numerous subcultures developed within the Archaic through time and over space, and these subcultures are reflected in the varied styles of blades they produced. Archaic blades range from very finely executed to rather crude. Figs. 5, 6, and 7 show an assortment of well made points that cover the entire temporal span of the Archaic period from its overlap with the Paleo-Indian period on its early end to its transition into the Woodland period at its later end (Figs. 5, 6, and 7, Archaic points). Interestingly enough, all of these blades, which represent thousands of years of development, were found within a limited geographical area in the vicinity of Stony Creek in Sussex County, Virginia. While this might seem highly unusual, it is, in fact, rather commonplace. Collectors and archaeologists have been making similar mixed finds in eastern Virginia and North Carolina for over a century. Not all Archaic points are as refined as those in Figs. 5, 6, and 7. Figure 8 shows an assortment of points from the middle Archaic. These points, locally known as Guilford points from their type location in Guilford County, North Carolina, range from well made to crude (Fig. 8, Guilford points). The points in the upper portion of Figure 8 are from the same area of Sussex County, Virginia, as the more refined points discussed above. The two points in the bottom of Figure 8 are actually from Guilford County, North Carolina. The top blade is very well done with carefully controlled flakes, whereas the bottom one is clunky. The salient points of the discussion in this paragraph are a) the Archaic subcultures were visiting the same resource areas through time and some maybe at the same time, b) all the blade makers were not equally talented, and c) not all cultures cared that much about the aesthetics of their blades.

Archaic blades were produced essentially the same way Paleo-Indian blades were made using percussion and pressure flaking. However, the Archaic cultures rarely ground the bases of their blades. The exception is that blades produced in the Paleo-Indian to Archaic transition period sometimes exhibit basal grinding. 4

As discussed above, producing stone blades took considerable skill and time, and the Archaic people, too, reworked their blades to keep them in service as long as possible. Figure 9 shows an assortment of Archaic points from eastern Virginia and illustrates how the full-size points likely would have been reworked, and thus shortened, to keep them in service (Fig. 9, Archaic points, full size and reworked). The top right blade was apparently broken in half and reworked into a hafted scraper.

Around the middle of the Archaic period, our early Virginia and North Carolina residents developed the need for heavier blades in the form of axes. While these axes were no things of beauty, they were functional. They were simply percussion flaked from small boulders (Fig. 10, Four flaked axes from Nansemond County {now City of Suffolk}, Virginia).

As the Archaic period progressed and transitioned into the Woodland period, the axes became more refined. Furthermore, the manufacturing process for these axes changed from simple percussion flaking to pecking, grinding, and polishing (Fig. 11, Four polished, grooved axes, bottom right example from Sunbury Area of Gates County, North Carolina, other three from Nansemond County, Virginia). This newly developed process involved repeatedly pecking the stone workpiece with another pointed stone, thus pulverizing and reducing the surface of the workpiece until it took the shape of the desired axe form. Intermittent grinding of the surface of the workpiece with another stone also was incorporated in this shaping process. Finally, the finished bit of the axe, and sometimes the entire axe, was polished smooth, probably with sand. Polished, grooved axes generally were of substantial size. The lower left example in Figure 11 is six inches long, has lost at least two inches of its bit, and still weighs three pounds. Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule. The diminutive axe in Figure 12 is barely three and a quarter inches long and weighs only six ounces (Fig. 12, Small axe). Was this a toy for a young family member? Probably not. Obviously, making polished, grooved axes was a time-consuming, labor-intensive process. The resulting axes were very effective tools and likely were treasured items. As with the blades discussed above, these axes were reshaped when damaged to extend their useful lives as long as possible (see Fig. 11, lower right axe from Sunbury was extensively reworked and is now much shorter than when made originally).

The Woodland Indians continued making polished, grooved axes throughout their period. In addition, they introduced a new variety of smaller chopping/cutting tool more akin to a modern hatchet. These polished stone tools are presently known as celts (Fig. 13, Four celts from Nansemond County, Virginia). Celts were likely hafted and used primarily for mundane, light, chopping chores; however, they probably were employed as weapons also. The same techniques used in the manufacture of polished axes were applied in making celts.

The bow and arrow was another major technological advancement of the Woodland Indians. This tool supplanted the spear as the primary hunting and fighting weapon, though the spear did not become obsolete. The arrow necessitated a shift in stone-blade morphology. Colloquially, all of the above-discussed projectile points of the Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods have been collectively called “arrowheads”, when, in fact, they were spear points. The Woodland Indians actually made arrowheads. Very generally speaking, these arrowheads were smaller, triangular blades, some very well executed and some not so much (Fig. 14, Assorted Woodland arrowheads). Interestingly, all of these points were found in the Stony Creek area of Sussex County as were those Archaic points in Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8. This group of Woodland points from essentially the same general location as the Archaic points further reinforces the argument made above that both Archaic and Woodland subcultures, and likely Paleo-Indians as well, were visiting the same resource areas through time (and some groups maybe at the same time), that all the blade makers were not equally talented, and that not all subcultures or even total cultures cared that much about the aesthetics of their blades.

One thing, however, did remain constant through all three of the major periods of American Indians in our study area of what is now Virginia and North Carolina. The basic manufacturing techniques for stone blades (percussion flaking, pressure flaking, and grinding) remained essentially the same. Two hammer stones are shown in Figure 15 (Fig. 15, Hammer stones). They, along with several other hammer stones, assorted flakes, scrapers, and a couple of broken and reworked Woodland arrowheads were found in close proximity on a workshop site on Knee Branch in Hertford County, North Carolina. Similar artifacts have been found on other Woodland workshop sites as well as on Archaic and even Paleo-Indian sites, such as the Williamson Paleo-Indian Site. Remember, these stone-working techniques were in use in our study area pushing 12,000 years and in other Stone Age cultures worldwide for even longer. Curiously, early humans, separated spatially and temporally, independently developed these basic techniques worldwide.

When the early European explorers and settlers first came to our study area, they encountered an advanced culture of Stone Age people. These first encounters, subsequent contacts, and eventually temporary and permanent settlements in the New World, would dramatically and forever change the culture and lives of the Woodland Indians. There were two significant, English contact locations in our study area. 5 The first, sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh, was a couple of failed attempts on Roanoke Island in what is now eastern North Carolina. In 1585, Raleigh named Sir Richard Grenville as Governor-General of Virginia and sent him to Roanoke Island to establish a colony. Grenville delivered Ralph Lane, his assistant, Thomas Hariot, the surveyor/historian of the colony, and the others to America to establish the colony. Grenville did not remain, leaving Lane in command. This attempt did not fare well, and a year later, Sir Francis Drake evacuated those remaining alive, including Lane and Hariot.

In 1587, Raleigh tried again. This resulted in Governor John White’s unsuccessful colony, later known as the Lost Colony. During White’s brief stay on Roanoke Island, he produced a portfolio of watercolors to document the local Indians and their lives. White returned to England to seek additional support for his colony, which was in dire straits. Fortunately, he carried his portfolio of watercolors with him. These original watercolors are now preserved in the British Museum in London. White was unable to return to his colony until 1590. When he arrived, he discovered the colony was gone. Because of adverse weather and time constraints, he was unable to locate any of its members, including his granddaughter, Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America.

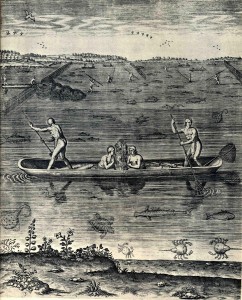

In London in 1588, Hariot published his account for Raleigh of Grenville’s attempt in the New World in his book, Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. In 1590, Theodore De Bry in Frankfurt, Germany republished Hariot’s work in his Grands et Petits Voyages, Volume 1, and he illustrated it with engravings he made from White’s watercolors. A comprehensive and very readable book on all of this information on the Roanoke Island attempts, including illustrations of White’s watercolors and De Bry’s engravings, is The New World by Stefan Lorant. There are two De Bry illustrations pertinent to our blades discussion. One is a front and back view of an Indian armed with a bow and arrows and of other Indians hunting deer with bows and arrows (Fig. 16, 1590 De Bry engraving, armed Indians). Here, the triangular, Woodland arrowheads are clearly visible. The second engraving shows Indians fishing using various methods (Fig. 17, 1590 De Bry engraving, Indians fishing). In the background, the Indians are using spears. This is proof that spears were not abandoned with the advent of the bow and arrow.

The second significant contact location in our study area, sponsored by the Virginia Company of London, was John Smith’s colony on Jamestown Island in Virginia in 1607. Here Smith and the colonists constructed James Fort. While this colony had a very shaky start beginning with the “starving time” the first year or so, followed by the massacres of 1622 and 1644, it nevertheless was the first, permanent, English colony in the New World. White man’s settlement in the New World was traumatic for both the settlers and the Indians, particularly for the settlers in the beginning but devastating for the Indian populations later.

As strange as it might seem, we know far more about the manufacturing of blades in what is now Virginia and North Carolina during the pre-contact Indian periods than we do after the arrival of the first Europeans. Concerning the Native American blades, we know the Indians were living here, as we have found millions of examples of their various blades and other artifacts. In addition, we have found numerous workshop and other sites where they lived and worked. If that is not enough evidence, live Indians equipped with their Stone Age tools greeted the early Europeans upon their arrival. Conversely, the iron and steel blades used in the study area after the arrival of the Europeans included both blades imported from Europe and blades made here. Distinguishing between the two can be challenging.

To begin our look at iron and steel blades, we must first distinguish the differences between iron and steel. An in-depth discussion on processing iron ore into iron and further into steel is well beyond the scope of this article. Iron is a naturally occurring element, usually found as iron oxide in nature. Iron oxide (ore) was converted through a melting process into elemental iron, which contained high levels of impurities such as slag, sand, and carbon. Further early refinement of this iron by heating and hammering produced usable wrought iron that could be fashioned by blacksmiths and other artisans into utilitarian objects. Steel is basically an alloy of iron and small, controlled amounts of carbon. 6 Depending upon the carbon content in the alloy, mild steel and high-carbon or tool steel could be produced. Iron is a strong, easily worked metal with many applications; however, iron cannot be hardened without further processing into steel and will not hold a sharp edge on blades. Mild steel is a stronger metal than wrought iron, and it works under the hammer about the same as wrought iron. Similar to wrought iron, mild steel cannot be hardened without further processing. High-carbon or tool steel is tougher still, and it can be hardened by heating, quenching, and tempering. Tool steel can be, and was, fashioned into blades that hold sharp edges, springs, and other objects benefiting from its properties. Also on this website, in our article, That Rusty Object – Is It Wrought Iron or Steel?, we provide a simple technique for determining whether a ferrous metal object is made of wrought iron, mild steel, or high-carbon steel. This methodology is mildly destructive and is not recommended for well-preserved artifacts.

In searching for examples of iron and steel blades made and/or used by the earliest English settlers in Virginia and North Carolina over 400 years ago, one needs to look no farther than Jamestown Island. In 1994, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA, now Preservation Virginia) launched its Jamestown Rediscovery project to search for any evidence of the 1607 site of James Fort. Conventional wisdom (rumors) persisted that the James Fort sight on Jamestown Island had eroded into the James River long ago. Archaeologist Bill Kelso (now Director of Archaeology at Historic Jamestowne), archaeologist Bly Straube (now Senior Archaeological Curator for Historic Jamestowne), and a team of other archaeologists and researchers, undertook the extensive research and excavation project. Remarkably, they discovered that only a small portion of the fort had eroded into the river and that most of the site remains on dry land! Extensive excavations of the site continue, and over a million artifacts have been recovered, including blades used by the first colonists. 7 Many of these artifacts are on display in the Historic Jamestowne Archaearium.

Edged blades known to have been used by the early English settlers in Virginia and North Carolina include: a) Swords of all types, b) Belt knives and daggers, both for practical use and show, c) Folding knives, d) Axes, both broad and felling, e) Halberds – ceremonial, axe-shaped polearms, used to designate military rank, f) Pikes – military, spear-shaped polearms used as weapons, g) Spontoons – ceremonial, spear-shaped polearms used to designate military rank, and h) Bills – sharp, curved, axe-like, military polearms often with a spike for thrusting, used as weapons. Here, let us distinguish the basic difference between bills and billhooks for purposes of this article. Billhooks are agricultural tools for chopping brush, saplings, hedges, etc. They date back at least to the ancient Greeks, and they are still in use today, known as bush axes or brush hooks. Around the fifteenth century, billhooks were “militarized” into polearms known as bills and used as weapons for combat. This is not to say that agricultural billhooks were not used as weapons also. During the sixteenth century, English troops were particularly fond of bills, especially for removing mounted cavalrymen from their horses. However, by the end of the sixteenth century, bills were obsolete. Nevertheless, they were still supplied to the Jamestown settlers as weapons, where apparently many reverted back for use as billhooks. 8

The following blades from the Jamestown Rediscovery, Preservation Virginia Collection are representative of what was being used by the early settlers in our study area at least through the mid seventeenth century and quite likely through the end of the century (Fig. 18, Scottish, basket-hilt broadsword), (Fig. 19, Hilt from Scottish broadsword), (Fig. 20, Halberd associated with Sir Thomas West, 12th Baron De La Warr who visited Jamestown in 1610, held by Michael Lavin, Jamestown Rediscovery), (Fig. 21, Felling axe), (Fig. 22, Broad axe), (Fig. 23, Dagger in sheath), (Fig. 24, Bill). Similar forms continued in use throughout the eighteenth century. Because these actual blades were found in situ in the excavations on Jamestown Island, we know for a fact that they were here. What we do not know for certain is where they were made. Most likely, the settlers imported all of them. Straube has postulated that most of the iron and steel blades used by the early settlers in our study area were imported from Europe and that the local blacksmiths and armorers were focused on repairing damaged weapons. 9 She would know better than anyone else.

Figure 25 is a halberd that dates to the mid seventeenth century, and it is of German origin (Fig. 25, Seventeenth century German halberd). While this halberd was purchased in eastern Virginia, there is no firm evidence that it was ever used here. Figure 26, on the other hand, is a poleax that was discovered in 1992 by Chris Calkins in the Petersburg, Virginia, area near the traditional, circa 1645 site of Fort Henry (Fig. 26, Poleax found in Petersburg, VA area). It most certainly was used here. Archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume of Colonial Williamsburg examined this object, and he identified it as being of Spanish origin. Further, Noel Hume opined that it was brought to the location where it was found by remnants of the Lost Colony. 10 Considering this poleax was found near the site of Fort Henry, a frontier post of the Jamestown colony, this postulated scenario of Noel Hume is not likely. A poleax is a traditional battleaxe, similar in shape to a ceremonial halberd; however, it was an actual combat weapon. The poleax was obsolete well before the beginning of the seventeenth century; nevertheless, apparently some were supplied to the Jamestown colonists along with obsolete bills. This particular poleax is owned by the Tourism Department of the City of Petersburg.

Figure 25 is a halberd that dates to the mid seventeenth century, and it is of German origin (Fig. 25, Seventeenth century German halberd). While this halberd was purchased in eastern Virginia, there is no firm evidence that it was ever used here. Figure 26, on the other hand, is a poleax that was discovered in 1992 by Chris Calkins in the Petersburg, Virginia, area near the traditional, circa 1645 site of Fort Henry (Fig. 26, Poleax found in Petersburg, VA area). It most certainly was used here. Archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume of Colonial Williamsburg examined this object, and he identified it as being of Spanish origin. Further, Noel Hume opined that it was brought to the location where it was found by remnants of the Lost Colony. 10 Considering this poleax was found near the site of Fort Henry, a frontier post of the Jamestown colony, this postulated scenario of Noel Hume is not likely. A poleax is a traditional battleaxe, similar in shape to a ceremonial halberd; however, it was an actual combat weapon. The poleax was obsolete well before the beginning of the seventeenth century; nevertheless, apparently some were supplied to the Jamestown colonists along with obsolete bills. This particular poleax is owned by the Tourism Department of the City of Petersburg.

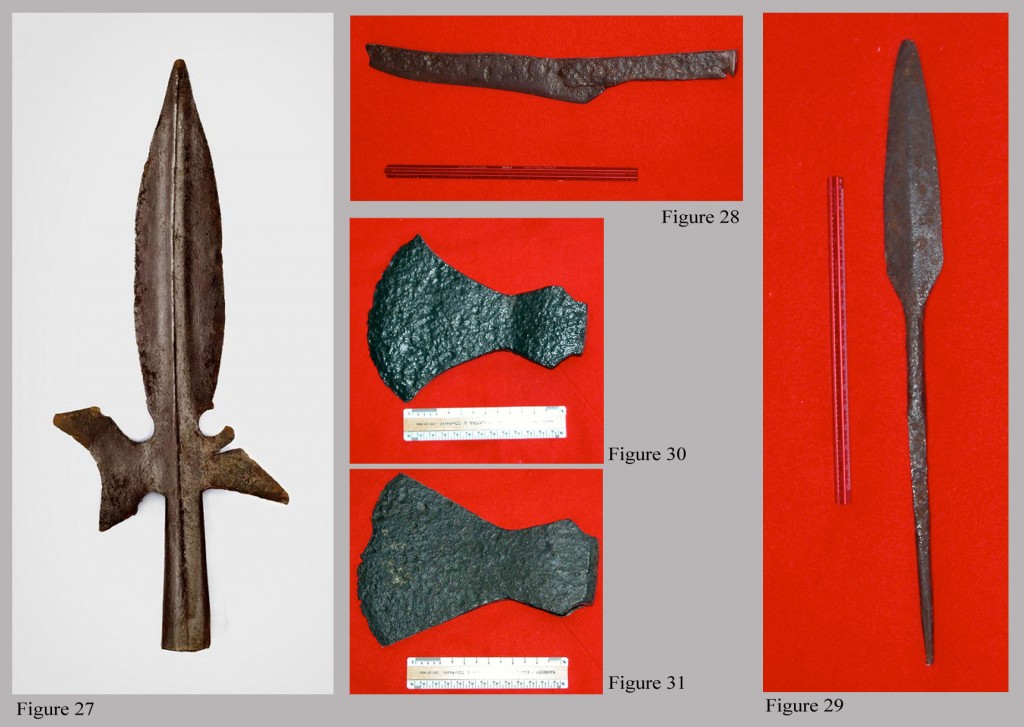

Figure 27 is an American-made ceremonial halberd in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Collection. It dates circa 1720-40 (Fig. 27, American-made Halberd). Figure 28 is a crude, blacksmith-made knife found in the vicinity of Menola in Hertford County, North Carolina. This field find was made and used in our study area, and it likely dates to the seventeenth century (Fig. 28, Early NC wrought knife). This knife filled an immediate need for someone, and little time was taken in its manufacture. The wrought pike in Figure 29 (Fig. 29, Early NC wrought pike) also was found in eastern North Carolina, and it was used and likely made in the area. This pike dates from the late seventeenth century to mid eighteenth century. Two broad axes of seventeenth-century form were found in eastern Virginia (Fig. 30, Broad axe, found along the Nansemond River in Nansemond County) (Fig. 31, Broad axe, found along the James River in James City County). These were probably imported, but they could have been made locally as well. Both certainly were used in Virginia in the seventeenth century and possibly into the early eighteenth century.

As previously noted, blade forms, similar to those of the seventeenth century, continued in use throughout the eighteenth century and even later. These three billhooks (Fig. 32, Billhooks), all found in Virginia, are carryovers from the earlier military bills. The top billhook is British and dates to the mid eighteenth century. The middle example is late eighteenth century French. The bottom billhook is early nineteenth century Virginia made. Another carryover example is this c. 1725, imported, Scottish broadsword with a Virginia background (Fig. 33, Scottish broadsword). This style sword developed directly from its seventeenth century and earlier counterparts such as the James Fort examples (see Figs. 18 and 19). Into the eighteenth century, civilian use of swords, daggers, and knives to show status began to wane somewhat; however, the military and functional uses of these blades obviously continued. Both Virginia and North Carolina were British colonies, and there was a thriving trade between the colonies and Great Britain up until the Revolutionary War. Consequently, most actual military arms and ceremonial arms of the British Army and the militias continued to be imported from the homeland. There was no exigent need for extensive manufacture of these military items in our study area; though some were undoubtedly made. Two major exceptions to the primary import of blades were axes and utilitarian knives. While not everyone in the colonies needed swords or ceremonial blades, virtually every family, if not every man, needed a knife and an axe. As a result, these blades were made here in substantial quantities by blacksmiths and gunsmiths to supplement imports, and uniquely American forms evolved. An excellent, comprehensive, illustrated source for information on blades used in the American colonies from the seventeenth century through the Revolutionary War is Swords and Blades of the American Revolution by George C. Newmann.

The typical axes seen in Figure 34 were used extensively in Virginia and North Carolina throughout the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth (Fig. 34, Felling axes). They were made primarily in Europe and, to a limited extent, in our study area. These four, eighteenth-century examples, as well as many others, were recovered all over Virginia. Most are less expensive iron axes without steel bits. (We will discuss steel bits later in this article.) It is difficult to say where these axes were actually made, but since they are lower-end examples and very formulaic, they probably were made in Europe and shipped here for trade with the Indians and for sale to budget-minded colonists. The one possible exception is the broad axe with the flared blade. Of the four shown, this one probably was made here rather than being imported. Note two of the axes have bogus touch marks to hype their quality to the unsuspecting. The felling axe in Figure 35, found in the Valley of Virginia, does have a steel bit and is of higher quality; however, it still has a bogus touch mark. This axe, too, was probably an import from Europe (Fig. 35, Imported felling axe with steel bit).

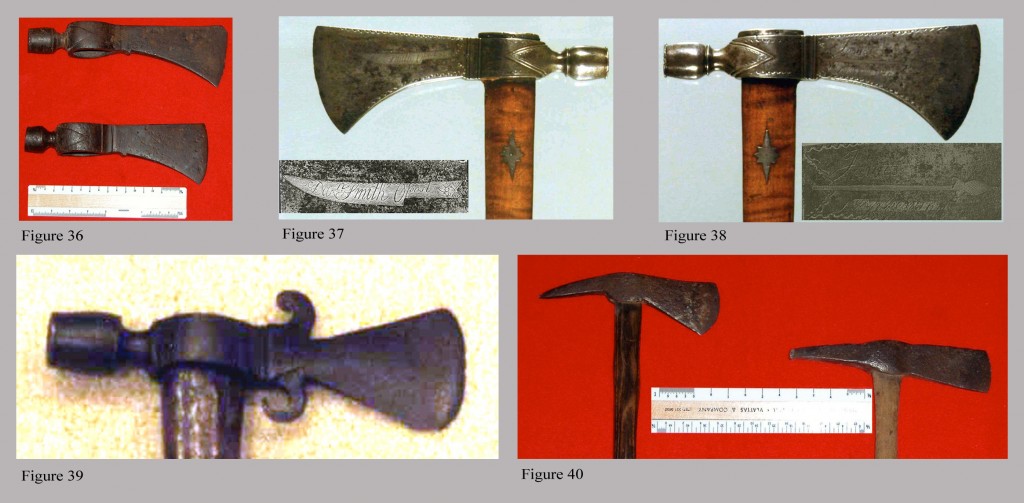

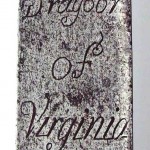

The two pipe tomahawks in Figure 36 were imports specifically for use in the Indian trade (Fig. 36, Trade pipe tomahawks). Both were found in the Valley of Virginia, and neither have steel bits. Virginia and North Carolina gunsmiths produced extremely well made pipe tomahawks for discerning clients, mainly on the frontier. Two such examples are included here. The first is a remarkable, eighteenth-century tomahawk made for Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee frontiersman, Indian fighter, Revolutionary War notable, surveyor, statesman, U. S. Senator, and William and Mary graduate, Daniel Smith (Fig. 37 and Fig. 38, show both sides of this tomahawk). They do not get any better than this example. On March 15, 1780, Smith recorded in his diary that he lost his tomahawk. There is a secondary name, James Stephenson, inscribed on the blade of this tomahawk above and below the spear (see Fig. 38). James Stephenson was a militiaman guarding Smith’s party at the time of the loss. Likely, Stephenson found and kept Smith’s tomahawk. 11 The second is a “spontoon”-type, pipe tomahawk (Fig. 39, Spontoon tomahawk). This eighteenth-century tomahawk descended in a Kentucky family. Of course, when it was made and used, Kentucky was still part of Virginia. Both the Smith and the “spontoon” pipe tomahawks have steel bits. While not common, riflemen and also Indians, when they could get them, used fighting tomahawks in our study area in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth. Two Virginia, spiked tomahawks are shown in Figure 40 (Fig. 40, American spiked tomahawks). Both have steel bits.

Around the middle of the eighteenth century, the American pattern of axe, a highly efficient chopping tool, was developed in the colonies, and it remains in use today (Fig. 41, American-pattern felling axes). All three of these eighteenth-century felling axes were found in Virginia and were likely made by blacksmiths in Virginia. They are of higher quality with steel bits. The curved, weld joint of the steel bit is clearly visible on the top axe. The joints on the other two axes are not as distinct, but they are there.

Throughout the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth century in our study area, belt axes were in widespread use by both civilians and many soldiers and militiamen who preferred belt axes to swords. The Indians also included belt axes in their arms inventories. These belt axes followed the basic form of European and American-pattern felling axes. An even smaller axe, the bag axe, another American innovation, likewise followed the two basic felling axe forms (Fig. 42, European form belt axes) (Fig. 43, American-pattern belt and bag axes). These latter diminutive axes were designed for carrying in a rifleman’s bag. In Figure 42, only the right example has a steel bit. The others are entirely of wrought iron. The seven belt and bag axes in Figure 43 have steel bits. The belt axe, second in from the right side, has decorative file work on its lower edge and a genuine touch mark, “MJ” (Fig. 44, Details of belt axe). All of the above belt and bag axes were found in Virginia or North Carolina, and some were still associated with rifleman’s bags or frontier families. Unlike the imported felling axes with their cookie-cutter profiles, belt and bag axes are more individual, like snow flakes. We have not encountered any belt or bag axes recovered in our study area that we thought were imported.

Generally speaking, fashioning blades of iron and steel in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries required a skilled artisan with the knowledge of the “art and mystery” of his trade and only basic tools – a forge, anvil, hammer, tongs, files, and sometimes a grinding wheel. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, steel was difficult, time consuming, and expensive to produce. Consequently, blacksmiths, armors, and gunsmiths used it only sparingly in applications where absolutely required, such as in springs, areas of high wear, and blades needing tough, sharp edges. For most other iron implements, wrought iron would suffice. In discussing axes, we have mentioned steel bits. In this application, a small piece of high-carbon steel was forge welded to a wrought-iron axe to provide it with a tough bit that would retain its sharp edge. Ken Schwarz, Master Blacksmith, Anderson Blacksmith Shop and Public Armoury, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, demonstrates how to make an axe with a steel bit (Fig. 45, Iron body of the axe is forged to shape) (Fig. 46, Iron body of axe is folded and forge welded together) (Fig. 47, Steel bit is fitted into place for welding) (Fig. 48, Steel bit is forge welded into wrought iron axe body, weld joint is visible). Figure 49 is another application where a steel bit was forge welded into an eighteenth century blacksmith’s cold chisel that was later used as a wedge. The weld joints in the wrought-iron body and along the steel bit are clearly visible (Fig. 49, Cold chisel with steel bit).

Knives in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Virginia and North Carolina were ubiquitous. There was relatively little demand for imported knives, as local blacksmiths, gunsmiths, and even individuals made them by the thousands to satisfy the needs for a utilitarian cutting and/or fighting blade. Knives were made of steel to retain a sharp cutting edge. Of course, traditional knives and daggers were made such as the formal dagger in Figure 50. This dagger from the Valley of Virginia has a whitesmithed guard, iron ferrule, and fitted leather sheath (Fig. 50, Formal VA-made dagger). The less formal, but still traditional, dagger in Figure 51 was fashioned from a spent file. It, too, is from the Valley of Virginia (Fig. 51, VA dagger made from a file). The pewter band around the hilt was a period repair to the hilt. In addition to the traditional forms, a vernacular form of knife also evolved. These knives were generally fitted with bone or deer-antler hilts. While many were professionally made, many more were homemade by the owners. The mid eighteenth-century belt knife with a bone hilt in Figure 52 descended in a Shenandoah County, Virginia family. It was probably blacksmith made, and it was found along with a rifleman’s bag and horn (Fig. 52, Early Virginia belt knife). Conversely, a gunsmith likely made the large, Valley of Virginia, belt knife in Figure 53 for a customer. This knife dates to the late eighteenth-early nineteenth century (Fig. 53, Gunsmith-made belt knife). A more diminutive and often more rustic style of these vernacular knives is the patch knife (Fig. 54, six examples of patch knives). Patch knives were carried in a leather sheath usually attached to a rifleman’s bag. They were used for small cutting jobs but primarily for cutting cloth patches for covering the balls fired from a rifle. Rifle balls fit snugly in a rifle barrel. The cloth patch around the ball actually engages the rifling or spiral grooves in a rifle barrel, thus imparting a stabilizing spin on the ball when fired from a rifle. The top knife and the knife in the center with the iron ferrule probably were professionally made. The rest likely were products of their owners, fashioned from files, broken saw blades, other knives, scrap pieces of steel, etc. All of these illustrated patch knives, dating from the early nineteenth century, were found in the Valley of Virginia, but other similar ones were made and used all over the frontier areas of Virginia and North Carolina. Wherever and whenever there was a man with a longrifle, there was a small knife for cutting patches.

Folding knives also were commonplace in our study area. Often they were used in lieu of patch knives and were carried in a rifleman’s bag. However, they certainly were not limited to use by riflemen. Unlike belt and patch knives of the period in our study area, folding knives were made both locally and imported in considerable quantities from at least the middle of the eighteenth century (Fig. 55, Folding knives from various locations in our study area). The top and bottom two knives were locally made. The second knife from the top is French, and the third knife down is probably Spanish. The basic forms of these knives remained unchanged from at least the seventeenth century.

Numerous, inexpensive, French, folding knives, known as “penny knives”, were imported into Virginia and North Carolina. They were popular with soldiers and militiamen during the French and Indian Wars and the Revolutionary War, as well as with long hunters and other frontiersmen. Bivouacked soldiers and encamped frontiersmen often had time on their hands and sometimes occupied themselves with craft projects, the period equivalent of producing World War I trench art. One such project was the carving of a “penny knife” into the full figure of a woman, including tiny, black, glass, trade beads for her eyes (Fig. 56, “Penny Knives” carved and un-carved). What once was a trifle for a friend or loved one, this carved knife is now a serious piece of folk art. Another less artistic, locally made example is a small knife with a whistle cut into its applewood handle (Fig. 57, Whistle knife).

Functional pikes and their ceremonial forms, spontoons, carried over from their seventeenth and early eighteenth century origins in Virginia and North Carolina well into the last half of the eighteenth century. The decorative spontoon in Figure 58 was made in Germany and is of the type carried by Hessian mercenary troops supporting the British during the Revolutionary War (Fig. 58, Hessian spontoon). 12 Americans captured a large number of Hessian, as well as British, soldiers in the decisive Battle of Yorktown, Virginia. This spontoon was purchased in eastern Virginia. The American pike/spontoon in Figure 59 was acquired from a family in Norfolk, Virginia, and it was likely made in that city for use in the Revolutionary War against the British (Fig. 59, American spontoon). This polearm still retains a portion of its original wood haft in its socket. The British attacked Norfolk on December 1, 1776. The city was essentially destroyed by fire from British naval bombardment and by rowdy local residents.

The above Hessian spontoon has decorative rings around its socket (see Fig. 58). It might be of interest to some to know how this was accomplished. In the following figures, master blacksmith, Peter Ross, formerly of Colonial Williamsburg, demonstrates the process of forge welding and shaping a similar ring on an iron shaft (Fig. 60, First a band of bar stock is partially fitted around the iron shaft) (Fig. 61, The cut bar stock ring is tightened onto the shaft) (Fig. 62, The shaft and ring are brought to welding heat in a forge and hammered in a swage to make the weld) (Fig. 63, Ring is welded to shaft) (Fig. 64, Ring is forged to near final shape) (Fig. 65, Ring and shaft are reheated and placed in a spring swage for final shaping) (Fig. 66, Ring and shaft are hammered into final shape in the swage) (Fig. 67, Ring removed from the spring swage). Note that Ross welded and finished the ring onto a solid iron shaft. For attempting the same work on a hollow socket as on the spontoon, a solid, well fitted, iron mandrel must be inserted into the socket to keep it from collapsing under the hammer blows. Final shaping and finishing were done with files.

By their very nature of use, sword blades must be sharp, flexible, and tough. These characteristics required the use of steel over wrought iron in their manufacture. Quality swords took considerable skill to make, were expensive, and were well regarded by their owners.

As previously discussed, Virginia and North Carolina were British colonies, and the full range of British military swords and other blades required by the British Army and colonial militias throughout the eighteenth century up to the Revolutionary War were imported. 13 With the advent of the Revolutionary War, all that changed drastically. There simply were not enough swords, blades, and other weapons on hand to arm the Continental Army and the state militias to fight the British. Also, the industrial base to produce the needed weapons was sorely lacking in the colonies. Virginia, North Carolina, and their sister colonies had to scramble to overcome these deficiencies. The most logical sources of supply for needed weapons were other European countries (France in particular), and the Americans began importing from them in quantity. To supplement the imports and to repair damaged weapons to keep them in service, new homeland industries were required and existing industrial concerns had to shift over to support the war effort. A prime example of this shift of a private industry was James Hunter’s Rappahannock Forge near Falmouth, Virginia across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg. 14 Also, Virginia established the Point of Fork Arsenal in Fluvanna County at the confluence of the James and Rivanna Rivers as a depot for collecting, repairing, manufacturing, storing, and distributing arms to Virginia troops. 15 Schwarz, in his on-going research, found documents indicating that the Continental Congress established a similar depot, the New London Armory, in Bedford County, Virginia to serve the arms needs of the Continental Army. However, there is no evidence of new manufacturing at New London. 16

Of note, American, James Potter, in New York City made particularly fine cavalry sabers during the war years that were desired and used by both Continental and British dragoons alike. Unfortunately, Potter was a Tory, New York City was under British occupation at the time, and his swords went to support the British cause. The Continental dragoons used Potter swords only when they could capture them. 17

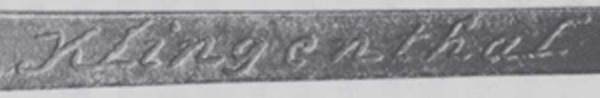

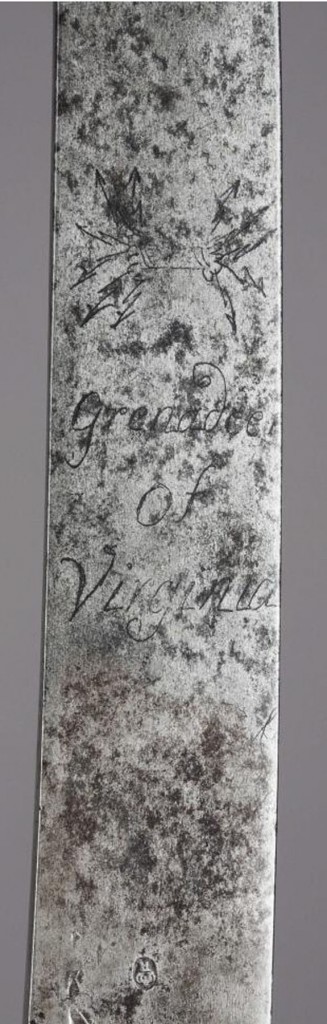

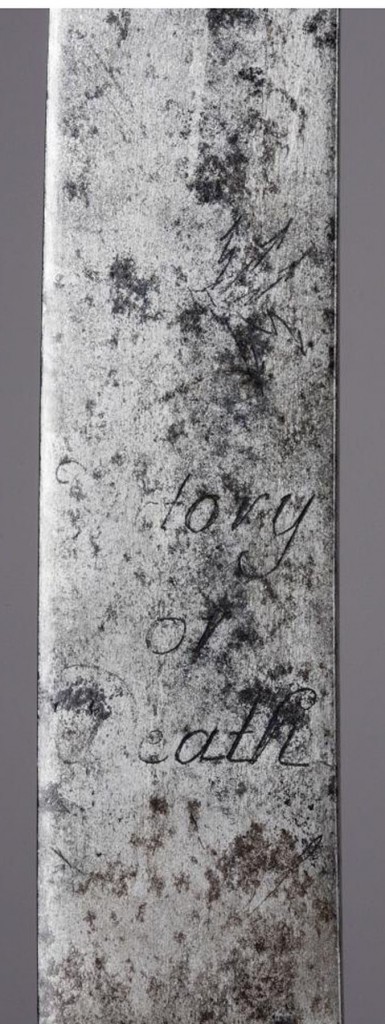

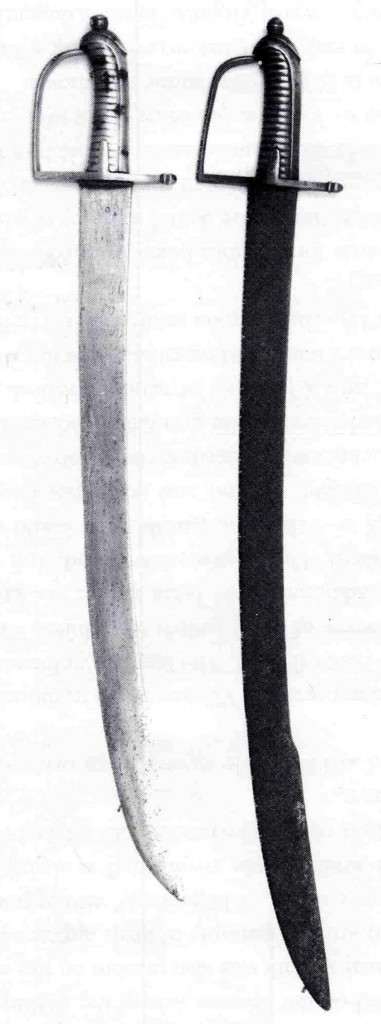

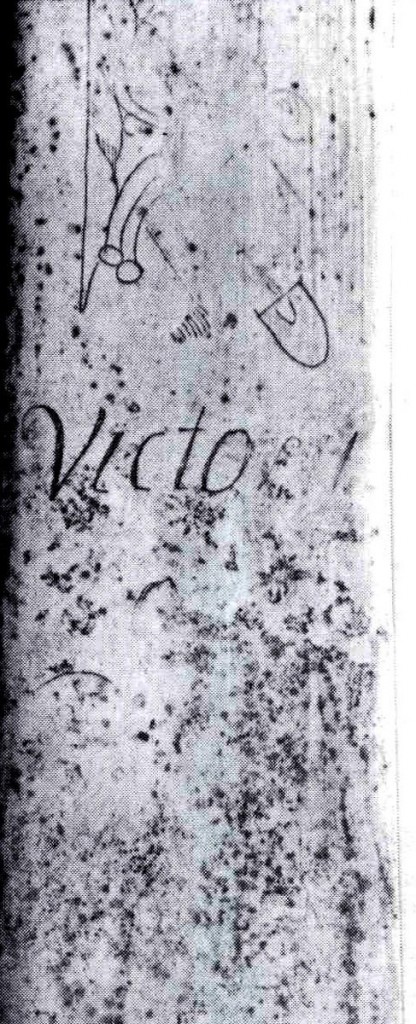

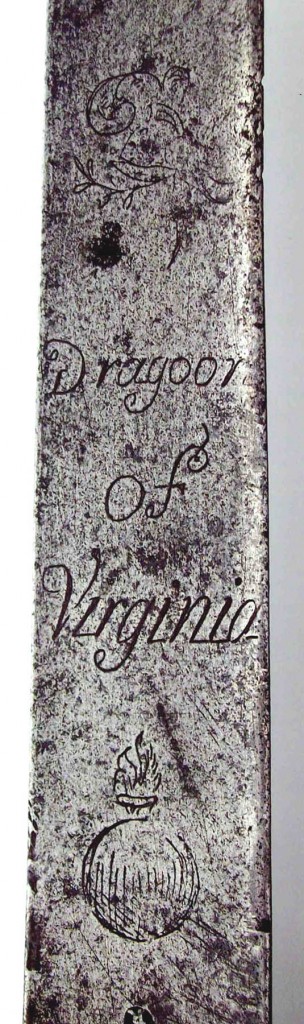

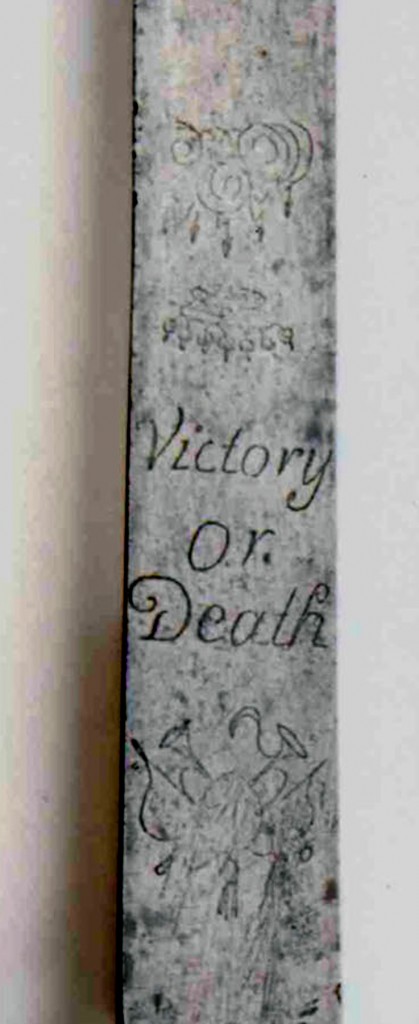

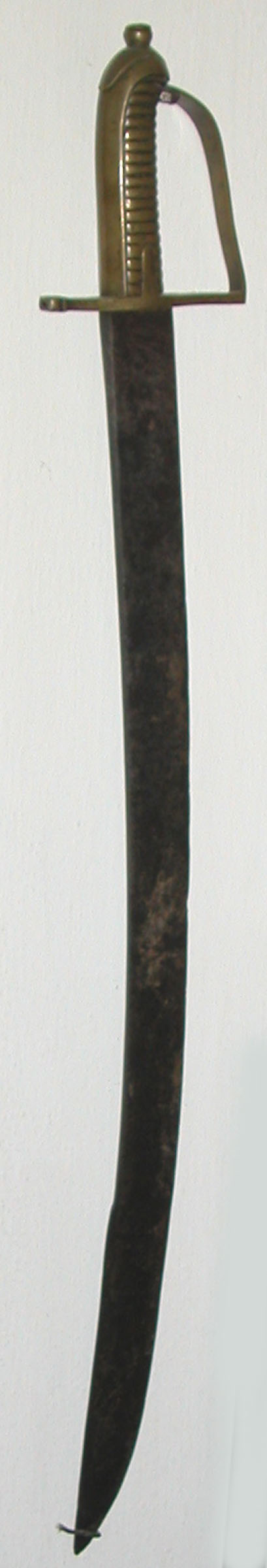

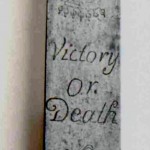

Virginia’s first, major, Revolutionary War, sword purchase has been well researched by Giles Cromwell, and all the following information about this purchase and the swords comes from him. 18 To make a long story short, Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia directed that assorted military stores, including swords, be procured for the state in France. While this procurement effort was shrouded in intrigue and questionable pricing, a contract was let in 1778 with Klingenthal near Strasbourg, France. The swords were completed in 1779 and shipped to Virginia. There were three types of swords produced by Klingenthal under this contract that numbered roughly 1500-2000 in total. The first two, grenadier and artillery, were similar, hanger-type swords for foot troops. The blade on the grenadier sword was 26 ½” long and on the artillery sword 23 ¾”. The third was a longer, dragoon sword of a different design for mounted troops with a blade 36” long. All the Klingenthal swords for Virginia were variously marked on both sides of their blades. In addition, all were marked “Klingenthal” on the top edges of their blades (Fig. 68, Klingenthal mark). The following figures illustrate the markings on the three types of swords (Fig. 69, Overall of grenadier sword) (Fig. 70, Detail of markings on right side of grenadier sword) (Fig. 71, Detail of markings on left side of grenadier sword) (Fig. 72, Touch mark on right side of grenadier sword, found on all Klingenthal swords) This sword is in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection. (Figs. 73, Detail of markings on right side of artillery sword, overall sword shape and blade markings on left side similar to grenadier sword) (Fig. 74, Overall comparison of artillery sword on left and grenadier sword on right) (Fig. 75, Markings on left side of artillery swords) (Fig. 76, Overall of dragoon sword) (Fig. 77, Hilt and markings on right side of dragoon sword, note American hilt on this sword, others had brass French hilts) (Fig. 78, Detail of markings in Fig. 77) (Fig. 79, Markings on left side of dragoon sword) (Fig. 80, Detail of markings in Fig. 79). At the end of the Revolutionary War, all the Klingenthal swords not needed by Virginia militia troops were placed in storage at Point of Fork Arsenal. While there are a few grenadier swords surviving, Cromwell reports that there are only four artillery swords and five dragoon swords presently known, and one of these dragoon swords is a dug relic.

Home-grown weapons and other wares were being made in Virginia on an industrial scale at Hunter’s Rappahannock Forge. Extant records show that he was producing muskets, pistols, wall guns, and swords for the American cause. He was also repairing weapons. 19 & 20 Very few Rappahannock Forge firearms remain. However, they are easily identified as most of Hunter’s guns were marked “Rappa Forge”. The swords are a different matter. We know for a fact from the records that he was making them; however, they were not marked “Rappa Forge” as on the guns. So, where are they, and what did they look like? There is compelling evidence that Hunter’s swords are the few remaining ones, mostly with Virginia provenances, marked on their hilts with an “H” (Fig. 81, Overall of Hunter sword) (Fig. 82, Hilt of Hunter sword) (Fig. 83, Hilt markings on Hunter sword). This sword is in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection. In Figure 83, the “H” mark is clearly visible. Additional markings are “1 T P L D N 22” which mean “this weapon was number 22 in the first troop of Pulaski’s Light (or ‘Legion’ of) Dragoons. Another “H” sword, number 17 of Pulaski’s 3rd troop, is in a private collection in Connecticut. This unit existed from 1778 until early 1780, when it was incorporated into Armand’s Legion after Pulaski’s death at Savannah the previous October. Adding credence to the interpretation of these markings are the identically styled markings for both Pulaski’s and Armand’s Legions found on some pistols made by Hunter, also for the Continental Light Dragoons”. 21 Several of these swords have imported blades that would indicate Hunter was refurbishing swords with new hilts as well as making new swords. 22

Casimir Pulaski, a Polish emigrant and cavalry expert, was a general in the Continental Army and a Revolutionary War hero. Pulaski County, Virginia, is named for him.

There is considerable archaeological evidence in the form of numerous incomplete blade and socket forgings that, in addition to repair work at Point of Fork Arsenal, socket bayonets were being made there as well. These bayonets were likely being made from near the end of the Revolutionary War until Point of Fork ceased operation in 1801. 23 Figure 84 is a Point of Fork Bayonet in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Fig. 84, Point of Fork bayonet).

Revolutionary War weapons manufacturing in North Carolina was not as extensive as in Virginia, but the effort was significant nevertheless. It consisted primarily of small contract operations. For example, in 1776, North Carolina directed Ambrose Ramsey to establish a gun manufactory in the District of Hillsboro and to produce 200 muskets, bayonets, etc. This effort was under funded and met with other environmental difficulties. It failed after only partially filling the order. Likewise, in 1778, North Carolina contracted with James Ransom in Bertie County to make muskets and bayonets. He only produced 36 complete guns, 24 bayonets, and assorted other parts. In 1776, the North Carolina Committee of Safety contracted with Timothy Bloodworth to manufacture muskets and bayonets. His production is not known. In 1776, North Carolina contracted with John DeVane and Richard Herring of the Wilmington Gun Factory. They produced 100 muskets and bayonets before the British destroyed their operation. 24

The Revolutionary War taught the fledging federal and state governments an important lesson about the necessity of an arms-making industrial base. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, federal armories were established at Harpers Ferry, Virginia and Springfield, Massachusetts. In the same timeframe, Virginia decided to consolidate its state-owned arms industry in Richmond. In 1798, the Virginia General Assembly authorized the establishment of an armory, thus the Virginia Manufactory of Arms in Richmond was born. Initial, limited production of muskets began in 1802. Around 1801, Point of Fork closed, and its materials, including its remaining stock of Klingenthal swords, were shipped to and stored in various locations in Richmond, including in the Capitol loft. The Point of Fork property was sold by the state in 1809. Cromwell has covered in detail all aspects of the Virginia Manufactory of Arms in his landmark book on the subject. This information comes from Cromwell. 25 The primary mission of the Virginia Manufactory of Arms was to produce for Virginia’s militia troops quality military arms, namely muskets, bayonets, rifles, pistols, and swords. First model rifles and pistols are extremely rare, on par with the “Rappa. Forge” wall guns, muskets, pistols, and “H” swords. The later model Virginia Manufactory firearms and all swords are more common survivors. For our article, we are focusing on the blades. Virginia Manufactory firearms were clearly marked on their lock plates as can be seen on this second model pistol made in 1813 (Fig. 85, Virginia Manufactory of Arms markings on firearms – Virginia, Richmond, and date made). The blades did not have the identifying, Virginia markings as found on the firearms; however, the iconic blade shapes and hilts make identifying Virginia Manufactory blades easy. The Virginia Manufactory produced four distinct models of swords: first, second, third, and artillery (Fig. 86, First model sword in its original, black-Japanned scabbard) (Fig. 87, Second model sword) (Fig. 88, Third model sword) (Fig. 89, Artillery model sword). All the first and second model swords originally were made with the long, curved blades as seen on the second model sword in Figure 87. These long, curved blades were generally not well received by the Virginia cavalry units, and many, along with their scabbards, were returned to the Virginia Manufactory of Arms for shortening. The first model sword in Figure 86 is an example of this modification. The third model sword (see Fig. 88) was made with a slightly shorter, less-curved blade with a clipped point. There were two slight variants of the artillery sword. One has a curved blade as seen in Figure 89. The other variant has a somewhat straighter blade (Fig 90, Artillery model sword with straighter blade). This artillery sword is in its original leather scabbard. Only two of these artillery swords with their original scabbards are known. Not unlike the Indians in prehistoric times reworking their broken blades into other usable tools, broken swords sometimes were reworked to extend their lives. The knife in Figure 91 is just such an example. It was made from a broken third model Virginia Manufactory sword (Fig. 91, Knife made from sword). Many, but not all, of the swords and firearms made at the Virginia Manufactory of Arms were stamped with regimental marks like “32, V’A REG’T” which is found on the sword in Figure 89 (Fig. 92, Detail of regimental marks on Fig. 89). Bayonets also were made at the Virginia Manufactory. Unfortunately, these blades were not marked as to manufacturer. They also underwent several design changes from their inception in 1802 to end of production around 1821. The most recognizable Virginia Manufactory bayonets are the particularly long ones standardized in 1807. These had blades 24” long and were 28 ¼” long overall (Fig. 93, Virginia Manufactory bayonet with its original 1807 musket) (Fig. 94, Close-up photo of 1807 bayonet in Fig. 93). Controversy surrounded these long bayonets as it did with the long swords, and production reverted back to shorter bayonets. The Virginia Manufactory of Arms ceased all weapons production in 1821 until the start of the Civil War. When Richmond fell to union forces, the Virginia Manufactory of Arms was destroyed. 26

For our final blade discussion, it is only fitting that we return to a recycled example from Cromwell’s research. According to Cromwell, in 1806, the governor of Virginia ordered that 187 of the remaining 600 Klingenthal grenadier swords stored in the Capitol be taken to the Virginia Manufactory of Arms. There they were to be cleaned, and all previous markings were to be ground off. New regimental markings for Norfolk County, “7, V’A REG’T” and for the Borough of Norfolk, “4, V’A REG’T” were to be stamped on the top of the blades (Fig. 95, Overall of refurbished Norfolk County sword) (Fig. 96, Regimental mark, “7, V’A REG’T” on Norfolk County sword in Fig. 95). In July 1807, the refurbished swords were placed in a hogshead and shipped on the sloop, Nancy, to Norfolk County. There, the regimental commander took his 80, Norfolk County- marked swords for his non-commissioned officers, and he delivered the remaining, 107, Norfolk-marked swords to Norfolk commanders. Only two of these 187, refurbished, and marked swords are currently known. Interestingly, there are also two other marked “7, V’A REG’T” swords known, one grenadier-style sword and one artillery-style sword. In addition to the Norfolk County regimental markings, these two swords still retain all their earlier Klingenthal marks as well. Were these two swords part of the 187 ordered but were not ground for some reason? Why is there an artillery sword in the mix when the governor ordered 187 grenadier swords? Were they Virginia militia swords already in possession of the Norfolk County regiment that had been previously marked for the regiment? Answers to these questions will have to await future research. 27

In conclusion, this article was never intended to be an all-inclusive study of the blades used in Virginia and North Carolina from stone to steel. That would not have been possible for us, especially considering our advanced ages and the enormous body of material. Certainly, there are stone, iron, and steel blades of various types in our study area that we have missed. For that, we apologize. However, we have tried to provide a general overview of the major types of blades used in what is now Virginia and North Carolina from the Paleo-Indians through around 1815.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

- Figure 29

- Figure 30

- Figure 31

- Figure 32

- Figure 33

- Figure 34

- Figure 35

- Figure 36

- Figure 37

- Figure 38

- Figure 39

- Figure 40

- Figure 41

- Figure 42

- Figure 43

- Figure 44

- Figure 45

- Figure 46

- Figure 47

- Figure 48

- Figure 49

- Figure 50

- Figure 51

- Figure 52

- Figure 53

- Figure 54

- Figure 55

- Figure 56

- Figure 57

- Figure 58

- Figure 59

- Figure 60

- Figure 61

- Figure 62

- Figure 63

- Figure 64

- Figure 65

- Figure 66

- Figure 67

- Figure 68

- Figure 69

- Figure 70

- Figure 71

- Figure 72

- Figure 73

- Figure 74

- Figure 75

- Figure 76

- Figure 77

- Figure 78

- Figure 79

- Figure 80

- Figure 81

- Figure 82

- Figure 83

- Figure 84

- Figure 85

- Figure 86

- Figure 87

- Figure 88

- Figure 89

- Figure 90

- Figure 91

- Figure 92

- Figure 93

- Figure 94

- Figure 95

- Figure 96

Published on: Feb 13, 2015

Endnotes:

- Unless noted otherwise in the text or Photo Credits below, all artifacts illustrated in this article are privately owned, and the photographs are by the authors. When a scale is included in a photograph, the scale is six inches long. This research was conducted for the Department of Collections and Conservation, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in an effort to take the thoughts that have been floating in our brains for years and reducing them to written words to share with others. Several of our sources, old personal friends and colleagues, are now deceased and many more are aging. These scholars were and still are pioneers in their respective fields. In this article, we have attempted to share that which we have learned from them and to provide a partial bibliography of their publications relevant to our study.

- Personal communication with Floyd Painter (now deceased).

- Following extensive personal communications with Floyd Painter and Dr. Ben McCary (both now deceased), we based these observations on our personal examination of numerous stone tools and reverse engineering for likely manufacturing techniques. We have tried these techniques to satisfy ourselves. We are, by no means, the first to propose these manufacturing methods, nor are we proficient at them. Numerous earlier researchers, including Painter and McCary, came to these same conclusions long before us and have published extensively on them.

- Personal communication with Floyd Painter (now deceased).

- Earlier Spanish and French explorers undoubtedly made incursions into what is now North Carolina and Virginia prior to the arrival of the English.

- We are discussing early steel here. In modern steel, additional elements are added to change steel properties to accommodate different uses.

- Personal communications with Dr. Bill Kelso and Dr. Bly Straube; For complete information on this monumental find, visit the Historic Jamestowne website at: http://apva.org/rediscovery/page.php?page_id=4 , or better still, go to Historic Jamestowne and see the James Fort excavations and Archaearium for yourself. You will not be disappointed!

- Personal communication with Dr. Bly Straube.

- Ibid.

- Personal communications with Mark Wenger and Willie Graham, including Graham’s recollections of conversations with Chris Calkins, who discovered the poleax, and with Ivor Noel Hume, who examined the object.

- Personal communication with Bill Guthman (now deceased) and from his article in Man At Arms.

- A nearly identical example is illustrated in Newmann.

- Newmann covers the full range of British swords and blades in this period, and we will not re-discuss them here.

- Personal communication with Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor and from her book on the Rappahannock Forge, Laying The Hoe.

- Personal communication with Giles Cromwell.

- Personal Communication with Ken Schwarz.

- Personal communication with Erik Goldstein, Curator of Mechanical Arts and Numismatics (Curator of Cool Guy Stuff), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Personal communication with Giles Cromwell and from his privately published treatise on the French swords for Virginia. Note, this treatise is currently being revised, updated, and edited, and it will be republished soon on this website.

- Personal communication with Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor and from her book on the Rappahannock Forge, Laying The Hoe.

- Personal communications with Giles Cromwell and Gordon Barlow.

- Quoted directly from Erik Goldstein’s description in the Colonial Williamsburg file on this sword.

- Personal communications with Giles Cromwell and Erik Goldstein.

- Personal communication with Giles Cromwell.

- All from the research notes of Garland Wood.

- Personal communication with Giles Cromwell and from his book on the Virginia Manufactory of Arms.

- Ibid.

- Personal communication with Giles Cromwell and from his privately published treatise on the French swords for Virginia.

Photo Credits:

Figs. 18-24 Courtesy of Jamestown Rediscovery, Preservation Virginia.

Fig. 26 Courtesy of Willie Graham and Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Figs. 37-39, 68, 73-80 Courtesy of Giles Cromwell.

Figs. 45-48 Courtesy of Ken Schwarz.

Figs. 27, 69-72, 81-84 Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

References/Bibliography:

Books

Cromwell, Giles. French Swords for Virginia, 1779. Ellicott City, MD: Courtney B. Wilson & Associates, 1995.

Cromwell, Giles. The Virginia Manufactory of Arms. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1975.

Eby (now MacGregor), Jerrilynn. Laying the Hoe, A Century of Iron Manufacturing in Stafford County, Virginia. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2007.

Goldstein, Erik. The Socket Bayonet in the British Army 1687-1783. Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray Publishers, 2000.

Goldstein, Erik and Mowbray, Stuart. The Brown Bess. Woonsocket, RI: Mowbray Publishing, 2010.

Hranicky, Wm Jack. Indian Stone Tools of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Alexandria, VA: Virginia Academic Press, 2002.

Kelso, William M. Jamestown Rediscovery II, Search for 1607 James Fort. Richmond, VA: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1996.

Lorant, Stefan. The New World. New York: Duell, Sloan, & Pearce, Inc., 1946.

Newmann, George C. Swords and Blades of the American Revolution. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1973.

Swayze, Nathan L. The Rappahannock Forge. Saratoga Springs, NY: American Society of Arms Collectors, 1976.

Periodicals

Babits, L. E. “The Evolution and Adoption of Firearm Ignition Systems in Eastern North America: An Ethnohistorical Approach.” The Chesopiean, June-August (1976).

Bottoms, Edward. “The Paleo-Indian Component of the Richmond Site, Chesterfield County, Virginia.” The Chesopiean, August (1972).

Bottoms, Edward. “Survey of North Carolina Paleo-Indian Projectile Points, Reports No. 1-5, Points 1-129.” The Chesopiean, (2008).

Eckard, Christopher S. “Hammerstone Types Found in the Coastal Plain of Southeast Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, September (1998).

Egloff, Keith and McAvoy, Joseph M. “A Tribute to Ben McCary.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, December (1998).

Guthman, William H. “Daniel Smith – Frontier Surveyor.” Man At Arms, March-April (1979).

Hranicky, Wm Jack and Painter, Floyd. “Projectile Point Types in Virginia and Neighboring Areas.” ASV Special Publication, Number 16 (1988).

Hranicky, Wm Jack. “Projectile Point Typology and Nomenclature for Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and North/South Carolina.” ASV Special Publication, Number 26 (1991).

Hranicky, Wm Jack. “Prehistoric Axes, Celts, Bannerstones, and Other Large Tools in Virginia and Various States.” ASV Special Publication, Number 34 (1995).

Hranicky, Wm Jack. “McCary Fluted Point Survey: Points 1000-1008.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (2004).

Johnson, Gerald H. “An Analysis of Lithic Material from the Williamson Site.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, December (1978).

Johnson, Michael F. and Pearsall, Joyce E. “The Dr. Ben McCary Virginia Fluted Point Survey, Nos. 846-867.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, June (1991).

Land, Howard D. “The Flint Perspective.” The Chesopiean, January-June (1979).

McCary, Ben C. “The Williamson Paleo-Indian Site Dinwiddie County, VA.” The Chesopiean, June-August (1975).

McCary, Ben C. “Bannerstones from the Dismal Swamp Area and Nearby Counties in Virginia and North Carolina.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, September (1975).

McCary, Ben C. “Semi-Lunar Knives from Tidewater Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1977).

McCary, Ben C. “Three Uncommon Atlatl Weights.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1977).

McCary, Ben C. and Bittner, Glenn R. “Excavations at the Williamson Site, Dinwiddie County, Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, December (1978).

McCary, Ben C. and Bittner, Glenn R. “The Paleo-Indian Component of the Mitchell Plantation Site, Sussex County, Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, September (1979).

McCary, Ben C. “Survey of Virginia Fluted Points, Nos. 537-603.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1980).

McCary, Ben C. “Survey of Virginia Fluted Points, Nos. 604-679.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, September (1982).

McCary, Ben C. “The Paleo-Indian in Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1983).

McCary, Ben C. “Survey of Virginia Fluted Points.” ASV Special Publication, Number 12 (1984).

McCary, Ben C. “Survey of Virginia Fluted Points, Nos. 733-770.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1986).

MacCord, Howard A., Sr. and Hranicky, Wm Jack. “A Basic Guide to Virginia Prehistoric Projectile Points.” ASV Special Publication, Number 6 (1979).

Melchor, James R. “Steel-Bitted Tools and Pattern-Welded (Damascus) Blades.” The Chesopiean, Winter (1999).

Melchor, J. R. and Ross, P. M. “Knobs, Knops, Finials, and Drops.” Anvil Magazine, v. 27, no. 1 (2002).

Melchor, J. R. and Ross, P. M. “Spring Swages.” Anvil Magazine, v. 27, no. 2 (2002).

Melchor, James R. “An Iron and Steel Primer.” The Chesopiean, Summer-Fall (2004).

Melchor, Jim, Newbern, Tom, and Melchor, Marilyn. “That Rusty Object – Is It Wrought Iron or Steel?” Edenton Historical Commission www.ehcnc.org, (2013).

Painter, Floyd. “Lancets, Unusual Items From Paleo Man’s Tool Kit.” The Chesopiean, February (1973)

Painter, Floyd. “One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: A Study in Discarded Tools and Weapons.” The Chesopiean, October-December (1982).

Painter, Floyd. “Paleo-Indian Cutting Blades: The Two Basic Traditions (A Revolutionary, Evolutionary Theory).” The Chesopiean, January-March (1983).

Painter, Floyd. “Have We Been Mutilating the Wrong Elephants?”

The Chesopiean, Spring (1988).

Patterson, Leland W. “Diffusion of Technologies in the Southeastern Archaic.” The Chesopiean, Winter-Spring (1994).

Patterson, Leland W. “The Clovis Point: A Changing Picture.” The Chesopiean, Spring-Summer (2001).

Peck, Rodney and Painter, Floyd. “The Baucom Hardaway Site: A Stratified Deposit in Union County, North Carolina.” The Chesopiean, Spring (1984).

Perrin, Ellen S. “Analysis of Endscrapers from the Williamson Site, Dinwiddie County, Virginia.” ASV Quarterly Bulletin, March (1977).

Rountree, Helen. “A Guide to the Late Woodland Indians’ Use of Ecological Zones in the Chesapeake Region.” The Chesopiean, Summer (1996).

Sasser, Ray R., Jr. “Regional Adaptation in the Eastern Clovis.” The Chesopiean, January-June (1979).