Are Cellarets from the East Coast and Sugar Chests from Kentucky?

By

P.E. Collie

This article examines cellarets and sugar chests, the historical contents and functions of the two furniture forms, and theorizes on the reasons for the seemingly disparate, geographic prevalence of the two forms.

Sugar chests have been found at greater frequency west of the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line (the geologic boundary between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain) while only a very few cellarets have been correctly attributed to the same western region. Why? The earliest cellaret designs, regional social customs, life styles, economics, and transportation pathways all provide clues why cellarets and sugar chests are found at varying frequencies in different regions.

Cellarets are considered by many antique furniture collectors as a Southern furniture form, which is effectively a lockable case to store alcohol, coffee, tea, sugar, or other valuable consumables. While cellarets appear with more frequency in the South, primarily along its coastal plain, they were produced in the other states. As with most Southern furniture, the form was adapted from related designs that originate from the Kingdom of Great Britain. In contemporary Southern vernacular, “cellaret” describes a divided crate-like enclosure that can be secured with a lock. Referred to historically as a “bottle case”, it is spelled other ways with “cellarette” seemingly the most common. 1

Many sideboards have one or two cellaret drawers. Early merchants had cellaret “crates” where customer’s bottles were stored for refilling and for the general safe keeping of case gin bottles (Fig. 1, Store crate) (Fig. 2, Interior of Fig. 1). 2

Previous researchers have believed sugar chests are a backcountry form found primarily in Kentucky and Tennessee. Note: Throughout this article, “sugar chest” may be used as a term of convenience but is intended to encompass all the various forms found west of the fall line. It is certainly true that the greatest diversity of the various sugar chest forms – sugar boxes, desks, sideboards, presses, stands, and other designs – are prevalent in Kentucky and Tennessee. But in fact, sugar chests were made throughout the Colonies with references in estate inventories appearing as early as 1686 in Tidewater Virginia.

Those found in eastern North Carolina, Virginia, and further south are generally sugar boxes and sugar boxes-on-frame (apparently referred to as “sugar stands” in early estate inventories). Sugar boxes, a diminutive blanket chest usually with internal dividers, appear to be the most commonly found form east of the fall line (Fig. 3, Sugar box) (Fig. 4, Interior of Fig. 3). 3 The period use of the term sugar box is borne out by an examination of estate records of Bertie County, NC, found in the North Carolina Office of Archives and History in Raleigh. An examination of a number of these estates has yet to reveal the term sugar chest. However, the term sugar box is found in the Bertie County estates of Thomas Whitmell (1779), William King (1787), James Wilkes (1798), Stephen Andrews (1800), Thomas W. Pugh (1802), and David Turner (1802). Cabinetmaker Micajah Wilkes’ Bertie County estate of 1842 contained two sugar stands. While this examination is of a single county and future research may show whether the use of this term is consistent east of the fall line, the term sugar box is an apt description of these small chests with or without partitions.

The greatest number of west of the fall line sugar chests found east of Kentucky and Tennessee has been in the general area of Danville, VA, and south along the inland trading path that ran toward Atlanta. Sugar boxes, small chests with or without partitions, appear to be more common than originally thought east of the fall line. However, sugar boxes-on-frame (sugar stands) known to originate from Virginia and North Carolina, near or east of the fall line, are rare (Fig. 5, Sugar box-on-frame) (Fig. 6, Interior of Fig. 5). 4 “Eastern” examples illustrated in this article represent those known to or owned by the small group of collectors reviewing and contributing to this article. If other eastern examples are known by readers of this article please contact us so those can be considered for inclusion in this study. Historic Edenton welcomes new information and civil debate on study papers.

Hepplewhite styles are typically the earliest “west of the fall line” sugar chests found although a greater number of Sheraton-style sugar chests are known. However, tapered legs may not necessarily guarantee that a piece is earlier than a similar one with a Sheraton-style turned leg. Unturned legs may simply result from lack of access to a lathe in the rural backcountry or a local stylistic preference. Paneled construction and skirts recessed behind vertical components are more reliable indicators of age as both indicate later methods of construction from the Hepplewhite to the later Sheraton styles. While sugar chests with Queen Anne legs are known, most appear to be out-of-period pieces dating as late as the 1840s.

By the 1830’s, some sugar boxes east of the fall line were sized to fit into large sideboards of the period. Richmond, Virginia, newspapers of the period carried advertisements for sugar boxes, probably like the one pictured in Figure 7, which was purchased from a Richmond estate. Ghost marks remain of a shelf used to break up sugar taken from a canister that fit beside the shelf (Fig. 8, Interior of Fig. 7). 5 A bottom slide would have allowed easy removal of any sugar that fell between the canister and shelf.

Designs and Uses of Cellarets

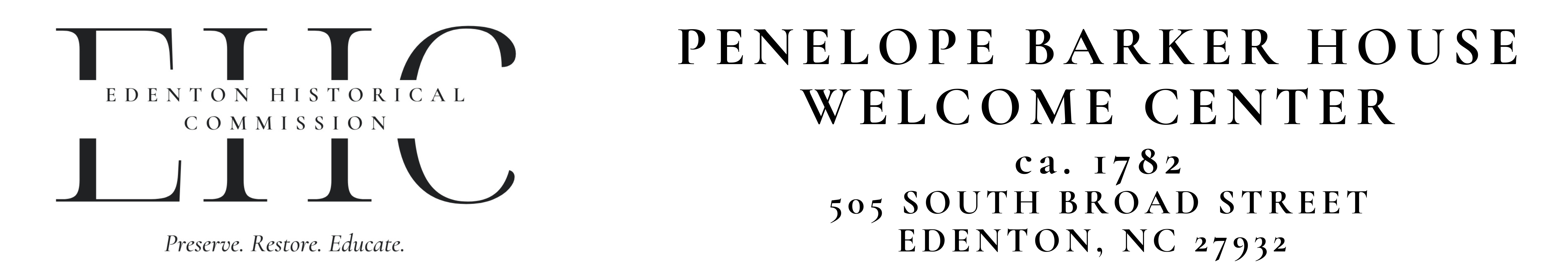

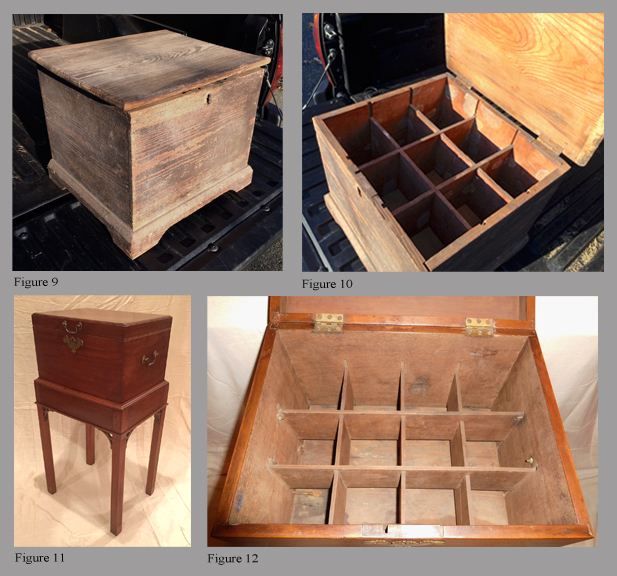

The two most often encountered forms of cellarets are boxes, that resemble diminutive blanket chests with internal dividers, and cellaret boxes elevated on a table-like stands—standing cellarets (Fig. 9, Cellaret box) (Fig. 10, Interior of Fig. 9) 6 (Fig. 11, Standing cellaret) (Fig. 12, Interior of Fig. 11). 7 It is unclear which of these two forms was the most commonly used in Colonial times, but standing cellarets now appear most often at auction sales and in private and institutional collections. Many of the bottle box versions may have disappeared as the need or desire for them diminished, and they were probably adapted into other uses, even converted into tool boxes. Cellarets were also made in other design forms such as a few known standing cellaret boxes that are elevated on a diminutive chest-of-drawers or cupboards with two-door cabinets instead of the more common use of table-like stands. Estate records of the period usually refer to these items as cases of bottles, cases and bottles, or cases and a certain number of bottles, offering no distinction among the forms.

Cellarets nearly always had built-in internal dividers, now sometimes partially or totally missing. These dividers are most often arranged and sized specifically for case gin bottles and occasionally fitted for associated serving glasses and funnels. The earliest cellarets, the rare Queen Anne cellarets, have one or two separate larger sections intended for other uses (Fig. 13, Interior of Queen Anne cellaret). Sugar is the most commonly believed intent for the larger divided sections but other valuable consumables, like coffee and later tea, were probably stored in the larger sections. It is also believed that larger containers, such as jugs or wine bottles too large to fit in a case gin bottle cavity, were stored in the larger sections. Two late eighteenth-century examples attributed to southeastern Virginia, probably produced in an urban center, are illustrated in Southern Furniture 1680-1830 on pages 531-533. 8

While the earliest cellarets might have been made before tea became a popular social custom in the 1750s, the taking of tea established demand for an entirely new group of accessories, but that is another story. However, many tea caddies were sufficiently small to fit into the larger compartments of cellarets, and top-mounted handles enhanced extraction from a cellaret and portability. It is also worth noting that many tea caddies had three compartments, two for tea possibly of different varieties, and one for sugar (Fig. 14, Tea box) (Fig. 15, Interior of Fig. 14). 9 Other observed evidence supports the likelihood that cellarets were also used to store sugar. Bowl-like devices of glass or pottery have been noted in which the legs of standing cellarets could sit dry while a separate moat-like perimeter can be filled with water or other fluid that would deter or kill sugar-loving pests such as ants trying to access the sugar; it is doubtful ants sought gin, even those from Down East. There is also evidence that sugar chests, so possibly cellarets as well, were set directly in a fluid container to ward off pests, to the detriment of the bottom of the legs or feet.

Many cellarets have drawers, slides, or both. For those with dividers intended for case gin bottles, slides are frequent, whereas when the larger compartments are present drawers are usually included.

Slides were probably used as a platform to mix drinks and divide sugar cones into smaller pieces. Drawers probably held corkscrews to draw corks from wine or gin bottles along with tools used to divide sugar cones into usable quantities (Fig. 16, Sugar nippers and hatchet). Sugarloaves formed into cones were the common form of commercially available cane sugar from Colonial times until late in the nineteenth century. Cane sugar was a major import commodity into Colonial America, and at times, it represented the largest imported commodity. Early Americans were very self-sufficient but coffee, tea, and sugar had to be imported.

Gin, rum, and brandy were common bottled products with gin being the most commercially available alcoholic beverage prior to the American Revolution. Many households made various “brews” on site or purchased alcohol products from local sources, though gin was also imported from England where it was so cheap that its excessive consumption caused serious societal problems in the eighteenth century. Other common drinks were shrub, a popular punch-like drink made from fruit, wine, vinegar, sugar, honey, and similar ingredients, and wine, which was both imported and produced locally.

Wine was produced throughout Colonial America both as homemade products and later as business ventures in America’s expanding frontier. Jean-Jacques Dufour arrived in Lexington, KY, in 1798, formed the Kentucky Vineyards Society, and planted the first vineyard, producing the first wine by 1803. North Carolina is home to the first cultivated American wine grape, the so-called Mother Vine on Roanoke Island and by the beginning of the twentieth century was the leading wine producing state in the U.S., then, prohibition.

While there are several types of bottles appropriate for a period cellaret, unmarked case gin bottles were the most prevalent in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Unmarked gin bottles can be dated within a narrow range based on bottle production methods, which will be detailed later. Some cellarets and sideboards with cellaret drawers were delivered to customers complete with a complement of custom-made bottles, glasses, funnels, and other accruements associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Many sideboard cellarets, the vast majority of sideboards are of the Hepplewhite and later styles, often used a different type of bottle, the newest fashion of round, clear-blown bottles fitted with decorative glass stoppers (Fig. 17, Standing bottles). 10 While a single cellaret drawer in a sideboard is the norm, sideboards with two cellaret drawers are known. Cellarets in sideboards are found either in large, lower drawers or behind lower compartment doors. One unusual example, constructed in Richmond, VA, contains a cellaret section accessed through a roll-top compartment on top of the sideboard (Fig. 18, Richmond sideboard) (Fig. 19, Cellaret in roll-top compartment of Fig. 18).” 11

Designs and Uses of Sugar Chests

Sugar chests typically have two or more divided sections that appear more appropriate for containers or items larger than the “standard” case gin bottles. Those on stands (sugar stands) typically have shorter legs so are lower in height, and many sugar chests have a greater total interior volume than the typical cellaret. The presence or evidence of dividers and a lock in a “blanket chest” too small to store blankets is very likely evidence of its use as a sugar chest (Fig. 20, Sugar box) (Fig. 21, Interior of Fig. 20). 12 However, it is also likely that not all smaller chests used to store sugar had internal dividers (Fig. 22, Sugar and bottle box) (Fig. 23, Interior of Fig. 22). 13 Those without internal dividers probably used smaller, separate boxes to contain various valuable consumables such as tea, coffee, and sugar. Square and round stains of gin bottles and larger jugs seen on the interior bottom of Figure 22 demonstrate the multiple uses of these small chests. Tills may or may not be present as they may have been used to store sugar “tools” or small valuables. Sugar chests rarely have slides, typically only drawers.

In Colonial times sugar cane was grown primarily in the Caribbean, the fluid produced by crushing and boiling sugar cane was reduced to sugary syrup and shipped in large wooden caskets called hogsheads. These were shipped to refiners nearer markets to be further refined and formed into cones, and then the cones were packed and shipped to consumers and merchants (Fig. 24, Sugar cone). Figure 24 is a modern example and is more refined than would have been found in Colonial times. In Colonial times, the two ends of the quality spectrum would have been white, which had been processed through several runs, and brown, which would still have contained a high percentage of molasses.

Early processed sugar assumed the form of a hard, conical, tapered shape (sugar cone) in molds that were used to refine sugar cane fluid into sugarloaf. The shape and hardness of the sugar cones also made it practical to pack large quantities for shipment. For use in the home, the cones had to be broken down into usable quantities. Common tools used to render sugar cones into a smaller, usable size were miniature hatchets or small cleavers. These were used to cut large chunks off the cones. Forged iron nippers were used to clip off smaller, table-ready pieces or pieces small enough to grind finer in a mortar with a pestle.

In addition to sugar, other valuable consumables such as coffee and tea were stored in sugar chests, as well as documents and money. The earliest Queen Anne cellarets may predate the widespread adoption of taking tea in rural Colonial America.

The period Queen Anne cellarets are of particular interest when delving into why sugar chests, particularly sugar stands, are uncommon along the NC and VA coastal plain. Period Queen Anne cellarets have at least one large compartment, drawers, and a slide. This could simply be a coincidence, it may be that all were made in the same shop, or in shops where close associations between cabinetmakers created a singular style. What is certain is that it was a purposeful design to make one furniture item serve multiple purposes. By providing a single cellaret to secure all valuable consumables only one expensive lock, key, hinges, and piece of furniture was needed. In the 1750 time frame, most houses in Virginia and North Carolina were small and interior space was at a premium (Fig. 25, Leigh-Hathaway house, Ca. 1759) (Fig. 26, Pendleton house, Ca. 1790). 14 Why have two pieces of furniture when one could be so designed to serve both functions?

Research published by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in The Chesapeake House, reinforces this theory. Drawn images based on documented inventories and known floor plans illustrate the cramped quarters created just by the furniture. 15 Add in the family, servants, and guests and the need to be thoughtful and prudent with furniture design is self-evident.

Status was another issue that affected taste in furniture. As long as sugar was a precious commodity, the presence of a sugar chest conveyed status and prosperity. It appears that the status associated with sugar extended later into the nineteenth century in Kentucky and Tennessee than near the east coast; transportation limitations made sugar more expensive and created seasonal supply limitations until steam-powered ships became common on the Mississippi. This may shed light on why elaborate and expensive sugar furniture forms with large storage capacities, such as sugar desks, are prevalent in Kentucky. Near the east coast sugar was more readily available and less expensive earlier so large caches of sugar were unnecessary, and the time when sugar furniture signified status had simply passed. This explains why east of the fall line during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, most furniture produced to store sugar took the form of small blanket chests, usually of yellow pine, with and without dividers, listed in estates of the period as sugar boxes (Fig. 27, Sugar Box) (Fig. 28, Interior of Fig. 27). 16 These were storage containers probably removed from the public eye, as opposed to the sugar chest of the west, usually constructed of more expensive woods such as cherry or walnut, and displayed to the public.

Nearly all research and conclusions into the evolution of early furniture styles and designs relies on the processes of the adaption of previous styles and forms into new designs and uses. So, if east of the fall line in 1750, a single standing cellaret contained alcohol, sugar, coffee, and spices, a separate sugar chest simply was not required. Approximately 50 years later (two generations) transportation-related issues maintained a need that led to sugar chests being ubiquitous in large swaths of the backcountry. In the backcountry, the high cost and seasonal limitations of transportation created the need to maintain household stores of sugar in quantity.

Who made the known Queen Anne cellarets? The cellarets illustrated below, one in the collection of Winterthur Museum, were almost certainly produced by Thomas White’s Northampton County shop (Fig. 29, Queen Anne cellaret) (Fig 30, Early photograph of Fig. 29) (Fig. 31, Interior of Fig. 29) (Fig. 32, Foot of Fig. 29) (Fig. 33, Drawer dovetails of Fig. 29). 17

The most telling feature of the Queen Anne cellarets is the carved volutes on the knee blocks and their similarity to knee blocks on examples attributed to Thomas White made during his residence in Perquimans County (Fig. 34, Queen Anne cellaret now in Winterthur Museum collection) (Fig. 35, Knee block with volute of Fig. 34). 18

The Influence of Rhode Island Cabinetmaking and Thomas White’s Role

The three main cabinet shops that comprised the Roanoke River Basin school of cabinetmaking were those of William Seay, the Sharrock family, and Thomas White. All three were located close to each other, with the Seay and Sharrock shops within ¾ of a mile of each other in northern Bertie County, and White’s shop was just five miles north in southern Northampton County. As with all early cabinet shops, there was a great deal of movement of journeymen among shops. Workmen went where they could find work and pay or ply their specialty, such as carving or turning expertise. These same workmen were also engaged in building houses for William Seay for area planters. While a number of pieces of Roanoke River Basin furniture exhibit characteristics of Thomas Sharrock’s Norfolk training, as passed on to his children, and William Seay’s background as a house joiner, some examples reveal a hybrid blending of characteristics of two or more of these shops in a single piece. Thomas White’s work in Perquimans County consistently shows characteristics of Newport, RI. Except for the work of Perquimans County cabinetmaker John Sanders, no other cabinetmakers of the period, unassociated with Thomas White, from the Roanoke River to the Atlantic, are know whose work exhibits these types of definitive Newport construction and decorative details. These Queen Anne cellarets’ cabriole legs exhibit strong White characteristics. While the knee blocks on one cellaret are replaced, those on the matching cellaret in the collection of Winterthur Museum again match the work of White (Winterthur Museum, Object number 2001.0047). The knee blocks continue to curve as they meet the leg stiles, matching a corner chair and a dressing table attributed to White (See The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820, by John Bivins, Jr., Figs. 5.120 and 5.120b, page 193, and Figs. 5.123 and 5.123a, page 196), as well as a second dressing table also attributed to White in the Bayou Bend Collection, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas (Accession number B.87.12). However, the feet on both cellarets have nothing in common with those seen on White’s work in Perquimans County. They match those found on Roanoke River Basin tables that contain feet with inverted trumpet pads believed to have been introduced by a workman or workmen from the Hay shop in Williamsburg, VA, only here with straight rather than inverted trumpet pads (See WH Cabinetmaker, by Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, Fig. 408, page 262. Compare to Fig. 32 above.) This blending of styles is not unexpected based on other Roanoke River Basin pieces, and it points to White’s shop in Northampton County as the likely origin of both cellarets. This attribution is further strengthened by an examination of one cellaret’s (Fig. 29) drawer dovetails. They are extremely well formed, elongated, equal sized front and back, and moderately thin. This description does not bring to mind dovetails found on pieces from the various shops of the Roanoke River Basin. It does, however, exactly describe dovetails found on the work of Thomas White while still in Perquimans County (See The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820, by John Bivins, Jr., Figs. 5.118i and 5.118l, page 189, and Fig. 5.120c, page 193. Compare to Fig. 33 above). Not unexpectedly, and as with the feet of these two cellarets, their drawer bottom construction conforms to that found on a number of Roanoke River Basin examples with bottoms dadoed into the drawers’ fronts and sides and nailed to the drawers’ backs.

Why are Cellarets Eastern and Sugar Chests Western?

Even today transportation pathways affect the availability of products, and they had an extremely significant impact in America’s early years. Alcoholic beverages, especially relatively inexpensive gins, were readily available along the coastal trade routes from the earliest days of settlement.

Gin’s “tradability” benefited from one of the earliest industry standards, square bottles approximately 11 inches tall with bases that fit within a 4 X 4 inch space. Gin bottles were among the first consumer products to be mass-produced to a “standard” in multiple factories in several countries. This “standardization” meant that any merchant along the supply chain could securely store standard-sized gin bottles in a premade “crate” either full or later as empty, customer-owned bottles to be filled from a larger container.

Beyond the reach of water-borne transportation, west of the fall line, bottles containing gin would have been at higher risk of breakage when transferred to ground-based transport and more expensive due to higher transportation cost. However, demand for alcohol did not diminish inland. Colonials drank nearly twice, and after the revolution nearly three times, the distilled spirits as contemporary Americans. The upward consumption trend was eventually interrupted by the temperance movement in the 1840s.

To slake this thirst, settlers and pioneers made their own spirits with stills, portable and stationary, and by fermenting and boiling (distilling) processes (Fig. 36, Portable copper still). 19 These homemade brews were likely stored in durable containers such as ceramic jugs that were of varying sizes, but these were typically larger than would fit within an opening sized for a case gin bottle (Fig. 37, Stoneware jug with X). 20 This influenced the design of storage containers by requiring larger storage compartments with sufficient volume to hold larger containers and enough imported goods to carry settlers through seasonal supply interruptions.

Bottled wine was also imported, and many bottles from France and Spain were “onion” or full liter bottles that were too large to fit in the openings sized for case gin bottles. Rings on the bottom board of sugar chests appearing to be from larger bottles, and of course, case gin bottles, have been noted. Particularly revealing are inlays mimicking wine bottles and glasses found on Kentucky furniture that hinted at the contents. Homemade alcoholic brews could be produced locally, especially if sugar was on hand, and stored in locally made stoneware jugs.

Transportation pathways also greatly affected sugar and similar imported consumables. The seasonality of trade routes made it prudent, if not necessary, to store enough sugar and other consumables to assure uninterrupted availability. The advent of steam-powered boats had a dramatic impact on trade along the Mississippi River and enhanced trade upstream on all navigable rivers, including those along the east coast. Steam-powered boats were plying all the major east coast rivers before the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

Sugar chests had become common household furnishings in many regions until the 1840s, when improvements in transportation pathways and dependable sources of sugar from local merchants became well established. In fact, sugar became so available and common that consumers east of the fall line began using buckets and tubs to store sugar as was done with flour and meal. Bertie County estates of Francis Pugh (1788) and cabinetmaker Thomas Sharrock, Sr. (1802) both contained sugar tubs. The estate of a second Francis Pugh (1808) contained a sugar tub as well as a flour tub. James S. Glover (1807), a Roxobel resident of Bertie County, died leaving an estate containing a sugar tub, a flour tub, and a meal tub. No Bertie County estates have yet been found that contained a sugar box and a sugar tub. The estates that contained a sugar box or a sugar tub contained holdings consistent with large or mid-sized planters. A number of lesser estates contained neither.

Because many early cellarets had larger storage compartments, for sugar and such, and supply transportation was not as problematic up to the fall line, sugar chests, other than the sugar box type, are rare east of the fall line.

By comparison, cellarets are rare west of the fall line with only a few known. Some cellarets with long histories in the backcountry appear to have originated east of the fall line and were taken west by early settlers during migrations. One such example was sold in 2009 at Brunk Auctions in Asheville, NC. Although this cellaret has a long documented history in Georgia, it appears identical to cellarets constructed by Joseph Freeman in Gates County, NC, where it was likely made.21 Further west in Kentucky and Tennessee, only a few locally made cellarets are known.

Other contributing factors depend on the region of the country. Western Kentucky and Tennessee depended on the Mississippi as the primary supply route for goods that could not be locally produced. Before steam-powered riverboats, supply runs were limited.

It is worth noting that as this article was being written several diminutive blanket chests that appear to be sugar chests, probably historically called sugar boxes, made east of the fall line came to light. Not all have dividers, but all are either too small to hold blankets or those with dividers have sections too small for use as a blanket chest. These traits lead to the belief these are sugar boxes. The small size of some may indicate either that they were intended to be portable, nothing like taking your own sugar on a trip, or may have been used as a convenience to hold sugar that had been rendered into smaller pieces from a larger container. Larger sugar boxes may have been used in merchant stores, warehouses, or for the transport of sugar cones from ships to markets (Fig. 38, Large sugar box) (Fig. 39, Interior of Fig. 38) (Fig. 40, Supports under Fig. 38). 22

How to Date Unmarked Case Gin Bottles

Case gin bottles were intentionally blown into a square shape for efficient packing into cases for transport. Cased gin was shipped from England and other European ports in divided crates with bottles packed in straw to reduce breakage. Square gin bottles were produced as early as the sixteenth century, the export of “Dutch bottles” by the Dutch East India Company began in 1602. Gin alcohol exports were relatively insignificant until the late seventeenth century but exploded near the end of that century. Now, discarded gin bottles exported from England and the Continent are found all over the world by bottle hunters, but many of those are washed up along waterways or are “dug” bottles that date from later in the nineteenth century.

Case gin bottles were produced by inflating a glob of molten glass attached to a hollow rod (blow pipe) into a square-shaped mold. As methods of production improved, the changes to the molds and pontil rods provide clues that can be used to approximate the date when a bottle was produced. While bottle production methods changed at different times in different countries, the changes occurred sufficiently close in time to provide a viable date range.

Clues to dating case gin bottles are listed below. Starting with the first to indicate the earliest feature with increasingly higher numbers indicating characteristics of later types. All date ranges are approximate and the dating methods have been edited into a simplified format from multiple sources. One excellent publication for those wanting to learn more about early bottles is Antique Glass Bottles: Their History and Evolution (1500 – 1850) by Willy Van den Bossche.

First, type of mold – first clay, second wood, third iron, fourth modern – automatic bottle machines. This feature is the most reliable and readily understandable clue to place case gin bottles into a narrow range. The list of clues following the mold type can be used to further refine dates of a case gin bottle when those features are clearly discernible. The left image shows an early case gin bottle bottom with side edges almost knife-like as made from the earliest times to 1800 in a clay mold (Fig. 41, Case gin bottle bottoms). The bottle on the right has rounded outside edges and was made from around 1790 to 1820 in an iron mold. Both of these bottles would have flat, obviously hand-applied lips on the spout, referred to as a pig snout. While cork stoppers were used, the lip permitted the use of cloth or leather covers that could be bound in place with a string or a leather thong.

Both case gin bottle types have sides that are tapered smaller from the top shoulder to the bottom. Case gin bottles with bottoms like the one on the left in Figure 41 with straight sides, not tapering along its length, date from 1720 to 1750. In the, mid-eighteenth century it was learned that a bottle blown into a tapered mold was easier to extract undamaged from the mold than a bottle blown into a straight-sided mold.

Second, type of pontil and base – first dime size pontil with almost no kick up to base 1600-1750, second nickel size pontil with medium kick up base 1725-1790, third large quarter size open pontil 1750-1825, bare iron pontil only 1750-1850. Note: the pontil is a raged area of glass under the base that is formed at the attachment point of the pontil when the bottle is separated from the pontil. Case gins bottles did not have pontils ground off.

Third, type of lip – first none or a captured pewter screw cap, second heated pushed-down and tooled, third applied pig snout, fourth marble shaped.

Fourth, color of glass – first light-lime green, second yellow-lime green, third black glass including brown and emerald green shades.

So-called “black glass” is actually different dark shades of brown and green in the glass color. The rarest colors in case gin bottles are a true grass green and bluish green. Light-green and yellow-colored bottles are rarer as these colors indicated the molten glass was wood fired before trees became scarce from over cutting. Black glass is coal fired which implies later production with manufacturing techniques approaching mass production so these bottles were made in greater numbers and less rare. These color methods of dating apply only to bottles made during and before the early nineteenth century. Black glass bottles are far more common.

The clear lead crystal bottles with gold trim (it is REAL gold) like those in “so-called” sea captain cellarets (tantalus boxes) are typically late eighteenth to earlier nineteenth century. These tantalus boxes were produced in England and on the Continent in a vast array of shapes, sizes, qualities, and fitments. Originally, many tantalus boxes included custom-made, decorative bottles that were often labeled for the contents.

Case gin bottles with applied shoulder seals were made from the earliest times but are extremely rare. Pictorial case gins (applied shoulder seals and side panels) were made from 1840-1910, and embossed (raised lettering) case gins were made from 1840 to the present. Many bottle collectors buy case gin bottles for the seal, with some actually collecting just the seals that are found broken away from the bottle. Case gin bottles with seals that date before or near the eighteenth century are extremely rare. To fill a cellaret with date-correct, sealed case gin bottles would likely exceed the value of all but the best cellaret.

Special thanks to Dwight Pettit, President of the Deland Florida M-T Bottle Club for assistance with the information on the merchant crate and dating case gin bottles.

The author also wishes to thank David Williams, Joe Jenkins, Maclin Cox, Sumpter Priddy, Tom Newbern, and Andrew Ownbey for their reviews, comments, and contributions.

Published on: Feb 9, 2016

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

- Figure 29

- Figure 30

- Figure 31

- Figure 32

- Figure 33

- Figure 34

- Figure 35

- Figure 36

- Figure 37

- Figure 38

- Figure 39

- Figure 40

- Figure 41

Endnotes

- Rather than expect four generations to learn and switch to the use of early vernacular this article will employ contemporary terms that are familiar and established. Where it is useful and clarifying, descriptive terms used in the past will be used when contemporary terms are either unestablished or not strongly established in long term use.

- The merchant crate is filled with dated bottles bearing various initials, probably those of regular customers. Based on the dates, December 1775, it is possible these survived in situ due to the disruption of the American Revolution. The crate with all 12 bottles inside was found in 2002 in a country store beside US Highway 301 by bottle dealers from Florida on their way to an antique bottle show in Baltimore, MD. The Colonial merchant may have been awaiting a larger container that never came. As previously noted, in inventories they were identified as “case of bottles” and the number of bottles present was often included. Figures 1 and 2. Store crate. OH 13; OW 18 ½; OD 14 ½. Private collection.

- Figures 3 and 4. Sugar box. Tidewater, VA. 1800-1810, probably constructed in Williamsburg, VA. Attributed to John Hockaday. Walnut and yellow pine. OH 17 ¾; OW 21; OD 17. Private collection.

- Figures 5 and 6. Sugar box-on-frame. Walnut and yellow pine. Inlay appears to be maple. Two brackets and all brasses replaced. OH 30; OW 16 ½; OD 16 ½. Private collection.

- Figures 7 and 8. Sugar box. Ca. 1830. Purchased from a Richmond, VA, estate. Painted green in the 20th century. OH 14 ½; OW 15; OD 12 ¼. Private collection.

- Figures 9 and 10. Cellaret box. 1800-1810. Descended in the Catlett family of Timberneck Farm, Gloucester, VA. Yellow pine with original Spanish brown paint. OH 15 ½; OW 18 ½; OD 16. Private collection.

- Figures 11 and 12. Standing cellaret. Ca. 1775. Found in Norfolk, VA. Walnut with poplar dividers and a yellow pine bottom. OH 38 ½; OW 20 ½; OD 16. Private collection.

- Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680-1830, The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA, 1997, pp. 531-533.

- Figures 14 and 15. Tea box. 1770-1790. Southeastern Virginia. Walnut and yellow pine. OH 6; OW 10 ¼; OD 7 ¼. Private collection.

- Figure 17. Standing bottles. From left to right: (1) An oversized case gin type bottle, late-eighteenth century, probably used at inns or in merchant stores, dubbed a “naughty boy”. OH 14; OW 5 ½; OD 5 ½. (2) Common square case gin bottle, early-nineteenth century. OH 10; OW 4; OD 4. (3) Clear decanter with gold trim and fitted blown glass stopper, mid-eighteenth century. OH 9; Dia 3. (4) Clear decanter with applied glass decoration and fitted pressed glass stopper, late-eighteenth to early-nineteenth centuries. This bottle type will not fit in most standing cellarets but was intended for sideboard cellaret drawers. OH 10 ½; Dia 4 ½. (5) Cobalt blue cruet, gold trim, labeled for shrub, with a fitted, ground, octagonal glass stopper. The pontil scar is ground smooth. OH 7 ½; OW 3; OD 3. Private collection.

- Figures 18 and 19. Sideboard with cellaret compartment. Circa 1825. Constructed in Richmond, VA. Mahogany and yellow pine. Documented to a house in Roanoke, VA, in the 1880s. The cellaret’s compartments measure five inches square, and round stains remain of the bottles they once held. OH 50 ½; OW 76; OD 28. Private collection.

- Figures 20 and 21. Sugar box. Found near the NC/VA border north of Bertie County, NC. It exhibits a number of characteristics of the Sharrock cabinet-making school. OH 15; OW 25, OD 16 ½. Private collection.

- Figures 22 and 23. Sugar and bottle box. Purchased in central Virginia. Yellow pine. OH 16; OW 25; OD 12. Private collection.

- Figures 25 and 26. The left section of the Leigh-Hathaway house was constructed between 1756 and 1759 by house joiner Gilbert Leigh. It is located in Edenton, NC. The left section of the Pendleton house was constructed ca. 1790. It is located in Nixonton, NC.

- Cary Carson and Carl R. Lounsbury, Editors, The Chesapeake House, Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation by The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 2013.

- Figures 27 and 28. Sugar box. Found near Raleigh, NC. Yellow pine. OH 20 ½; OW 33; OD 16. Private collection.

- Figures 29, 30, 31, 32, and 33. Queen Anne cellaret. Ca. 1770. Figure 30 documents this cellaret when discovered in the 1920s by antique collector W.E. Massenburg in Rocky Mount, NC. Walnut and yellow pine. OH 40; OW 32; OD 19. Private collection.

- Figures 34 and 35. Queen Anne cellaret. Ca. 1770. Currently in the collection of Winterthur Museum. Walnut and yellow pine. OH 37 ½; OW 32; OD 17. Courtesy, Sumpter Priddy III, Inc.

- Figure 36. Portable copper still. Dovetailed and soldered top and side, seamed and soldered spout and bottom. Can function as an alcohol still using fire underneath to evaporate alcohol through a separate “worm” or as a beer cooker by suspending the still from the handles in a wagon during warm weather. The agitation from movement of a wagon during transport would help ingredients “work”. OH 9; Widest Dia 10. Private collection.

- Figure 37. Stoneware jug with classic X signifying alcoholic contents. Note that an X and skull and crossbones that indicated deadly contents were close graphic cousins. OH 11 ¼; Dia 6 ¼. Private collection.

- This cellaret was sold by Brunk Auctions of Asheville, NC, on May 30, 2009, listed as lot 75.

- Figures 38, 39, and 40. Sugar box. Recently purchased at an Edenton, NC, estate sale. Ca. 1750. Yellow pine. Top originally secured by snipe hinges. Original runners, placed under the box to lift it off the floor, were relieved in the middle to limit contact with the floor. Holes drilled into runners are modern. Property of Cupola House Association.