Hidden in Plain Sight

A Research Note by Jim Melchor and Tom Newbern

With input from Libby Pope

The Chowan County Courthouse of 1767 is located in Edenton, NC (Fig. 1). An excellent history and chronology of this historic courthouse is contained in a booklet commemorating the restoration of the courthouse, The Chowan County Courthouse 1767, Celebration Of A Re-Awakening. This booklet was compiled by the Edenton Historical Commission and issued in October 2004 in conjunction with the reopening of the courthouse after its restoration.

In June 2009, the Lords Proprietors Inn, a local landmark in Edenton consisting of several buildings and lots, sold at auction. The furnishings of the Inn’s buildings on the site also were sold. Lords Proprietors house (Fig. 2) was built in 1902 for the White and Bond families, and it is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Inn served as a bed and breakfast from around 1987 until closing for the auction. Subsequent to the sale, new owners of the property have reopened the old Lords Proprietors Inn as the Pack House Inn.

One of the buildings on the Inn property, now formally known as the Pack House (Fig. 3), originally was a service building (pack house) located on the Strawberry Hill farm property just outside of Edenton on Route 32. Lords Proprietors Inn owners, Jane and Arch Edwards, purchased this pack house with its contents in the late 1980s from then-owner of the Strawberry Hill farm property, Gillian Wood. It, with its contents, was moved from the farm to its current location on the Inn site.

Libby Pope, who has owned the late-eighteenth century Strawberry Hill manor house (Fig. 4) since 1998, attended the auction sale of the Lords Proprietors Inn. She saw the subject document press in the Pack House, suspected it was a local piece of importance and purchased it at the sale. She conducted her own limited research on the press, had needed restoration work done, and moved the press to her Strawberry Hill home. Based on the document-press form and its large size, Ms. Pope reasoned that the press must have been associated with a large farm operation, a mercantile establishment, or a courthouse. She favored the courthouse option and invited us to further examine the press. Her intuition appears absolutely correct. Much of the information presented in this research note is based on conversations with Ms. Pope.

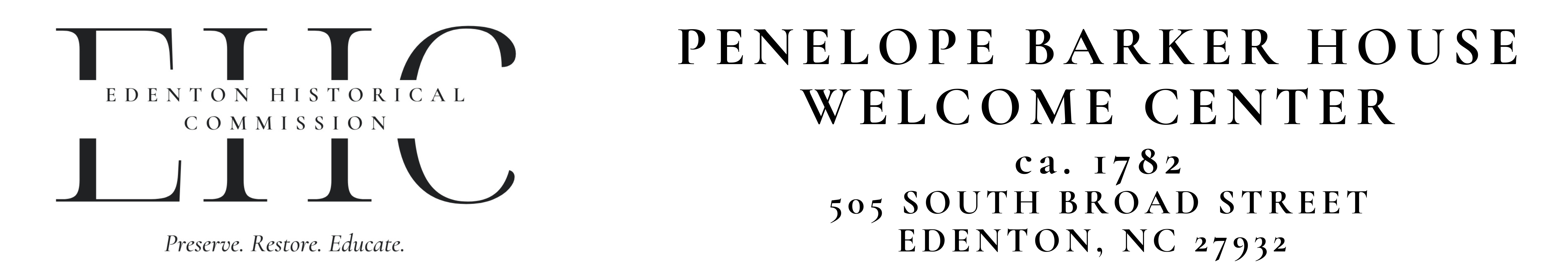

This document or book press (Figs. 5 & 6) is constructed entirely of yellow pine, and it is quite large, 92” high x 75” wide x 18” deep. Its construction characteristics, including raised, fielded panels, wrought-iron fasteners and hardware, heavy framing members, joining techniques, etc., all indicate an eighteenth-century to possibly early nineteenth-century construction date. The front and proper left side of the press are grain painted in a style common from around the 1840s to the 1880s. The proper right side of the press has never been painted. We will return to this paint scheme later.

Over years of research in northeastern North Carolina and eastern Virginia, we have had the opportunity to examine numerous document or book presses, both freestanding and built in, associated with home and plantation use, mercantile establishments, courthouses, and clerk’s offices. Generally, with few exceptions, the presses built for home and store use are smaller freestanding pieces, and they rarely exceed the size of a desk and bookcase or chest on chest. Often, they are constructed as a combination desk and press or chest and press. Conversely, document presses in courthouses and clerk’s offices tend to be larger. Often, they are built in, and in some cases, both built-in and freestanding presses are encountered in the same courthouse/clerk’s office complex.

Based primarily on its size, arguments for this document press being for courthouse or clerk’s office use are compelling. Further, based on its size, the courthouse or clerk’s office for which this press was constructed likely conducted considerable public business, unlike that which would be expected in a quiet rural setting. Also, a press of this physical stature would not lend itself readily for home reuse after its public service ended, nor would it be easily transported far from its original site by period or even modern conveyances.

Assume for a moment that this press, indeed, was for court use and has not strayed far from its original home. Where is the closest major courthouse that would have needed a press of this size in the period that this press was built? The answer, of course, is the 1767 Chowan County Courthouse in Edenton less than a mile from the pack house on the Strawberry Hill farm where it resided until the pack house and its contents were moved to the Lords Proprietors Inn site in the late 1980s.

An examination of the newly restored Chowan County Courthouse quickly revealed one logical location for this large document or book press, the clerk’s office (Fig. 7). This corner in the clerk’s office is a perfect fit for the press. A coincidence, possibly so, but lets examine the courthouse records. According to research by Mark D. Brodsky in 1989 (The Courthouse At Edenton A History of the Chowan County Courthouse of 1767, published by Chowan County, Edenton, NC), the presumed undertakers of the courthouse construction, Gilbert Leigh and John Green, on 20 Sept. 1770, were allowed eight pounds for one book press and three pounds, ten shillings for one corner book press for the clerk’s office. The built-in corner press is still in situ in the clerk’s office, and as noted, there is a perfect vacant corner in the clerk’s office for a freestanding book press of the exact size of the subject book or document press in this research note. Also, the wrought-iron hinges on the built-in corner press exactly match the hinges on the freestanding press (Fig. 8 & see Fig. 5). Both sets of hinges contain six holes along each vertical leg, and the center hole of each horizontal leg is set off-center in the same manner to avoid the rail and stile joints of each press’ door. This evidence is pushing coincidence well beyond belief.

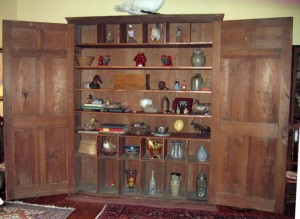

If this evidence were not enough, there are two pencil signatures, one clear and one faint, both George, on the inside of the proper left door (Fig. 9) (The upper portion of this figure is the clear signature as it appears on the door, while the lower portion of this figure is the same signature enhanced for clarity). The faint signature is not illustrated. Was George the maker? Based on the above arguments, that is not likely. Further, furniture signatures are usually whole names, last names, initials, ciphers, or symbols. True, George could be a last name; however, it is more likely that the name on this press was that of the owner. Who would own the Colonial Period 1767 courthouse, its furnishings, and the records therein? King George, of course, would have been the owner.

The final aspect of this document or book press to be discussed is the grain painting. As previously mentioned, the front and proper left side of the press are grain painted, while the proper right exterior side of the press has never been painted (Fig. 10 & see Fig. 5). Now, if you turn your attention to the vacant corner in the clerk’s office (see Fig. 7), it readily becomes apparent that if this press were sitting in this location, as suggested, the proper right end of this press would be butted against the wall, thus unseen and unavailable to be painted when the rest of the press was painted. Another coincidence? We think not.

Obviously the grain painting on this press post-dates its construction by many years. What evidence do we have that the clerk’s office actually was grain painted? Referring back to Brodsky’s research, court records indicate that in 1875 an order was issued to “grain” two bookcases and the baseboards of the registrar’s office. Essentially, this evidence becomes final proof for the argument that this document or book press originally was built for the clerk’s office in the Chowan County Courthouse in Edenton and that it remained there at least past 1875.

Who was the grain painter of 1875? We do not know, but he or she was active in the Edenton area. This press now resides in the front passage at the Strawberry Hill manor house. The passage here has a later, grain-painted wainscot. While not exactly matching the grain painting on the press, it is sufficiently close to attribute the work to the same hand (see Figs. 5 & 10). Further research on grain painting in the Edenton area likely will reveal more work by and possibly identification of this painter.

Finally, when was the document press removed from the courthouse complex and why? Again, we do not know for certain. However, according to local tradition, the press was removed around 1920 and replaced by more modern, steel file cabinets. The old, out-dated press subsequently was relegated to the pack house on the Strawberry Hill farm, where it was used for storage.

Since around the 1920s, this important document press has traveled around the Edenton area, never far from its original home, the courthouse. It is now time for this press to make one last trip and return to its original spot in the clerk’s office in the Chowan County Courthouse for all to enjoy!

For a slideshow of all of the images contained in this article, click on any of the thumbnails below:

- Figure 1, Chowan County Courthouse

- Figure 2, Lords Proprietors Inn

- Figure 3, Pack House Inn

- Figure 4, Strawberry Hill Manor House

- Figure 5, Document Press Exterior

- Figure 6, Document Press Interior

- Figure 7, Clerk’s Office

- Figure 8, Hinges

- Figure 9, Left Door

- Figure 10, Right Exterior Side

Published on: Feb 8, 2013