By

Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

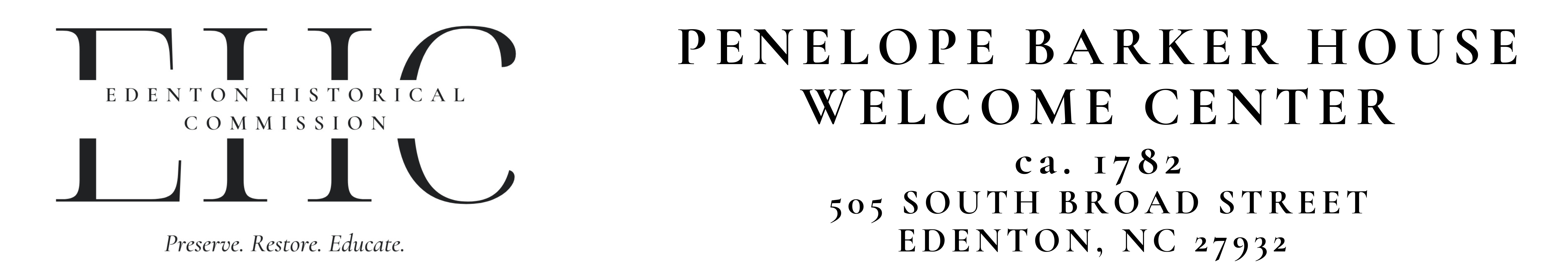

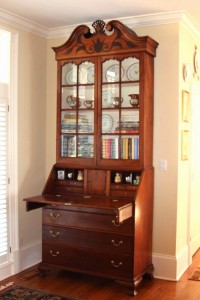

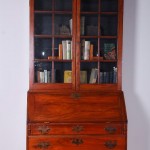

On June 9, 2012, auctioneer and decorative arts expert Ken Farmer was called on to identify an extravagant desk and bookcase during the taping of an episode of PBS’s Antiques Roadshow in Boston, Massachusetts. Farmer immediately recognized that this was not a piece of Massachusetts or northern origin, but in fact hailed from the American South. He identified it as the work of Bertie County, North Carolina, cabinetmaker William Seay. Farmer explained to the show’s viewers that the scrolled pediment, flame finial, articulated arches over the upper lights of the bookcase doors, and use of southern yellow pine were all indicative of Seay’s work (Fig. 1, Seay desk and bookcase).

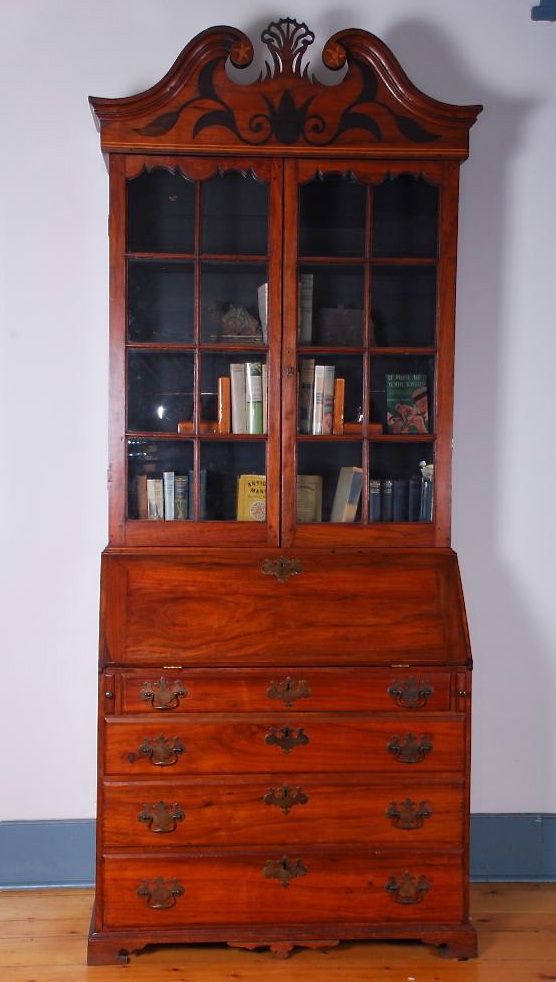

An unusually detailed history accompanied the desk and bookcase. It was purchased in 1924 in Petersburg, Virginia, by historic novelist, Kenneth L. Roberts. Roberts also served as editor of the book Antiquamania, published in 1928 (Fig. 2, Title page of Antiquamania). In it, he documents the specifics of his purchase of the desk and bookcase in a chapter entitled “General Antiqueing With Experts”. Roberts humorously details how he and his two companions participated in a “raid into Virginia from northern territory”. The acquisition and removal of southern decorative arts to Pennsylvania and points north was commonplace during the early years of the twentieth century. Local tales exist to this day of some enterprising individuals of northern extraction who resorted to railroad cars to remove their purchases northward, where the pieces often received new historic narratives. Fortunately, Roberts retained the known history of this desk and bookcase. Roberts related how he informed his companions that he was “considering the purchase of a large slant-top scrutoire with a glass-doored cabinet top” for $250.00. He described its condition as missing its feet as well as some panes of glass from its cabinet doors, with only a few small pieces of wood missing from its fall front. His companions noted that with little effort it would be a piece “well worth having”. Roberts stated, “…all three of his hosts enthusiastically recommended that he purchase it.”1

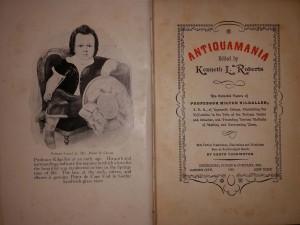

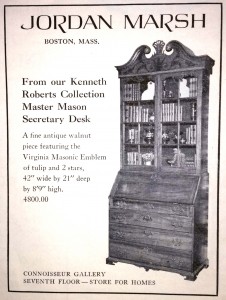

At the conclusion of his hunting expedition to the South, Roberts returned to his home in Kennebunkport, Maine, with his prize. He documented his purchase on the bottom of one of the interior desk drawers, noting that George Goodwin of Kennebunkport executed the necessary repairs, apparently including the feet seen on the piece during the taping of the Antiques Roadshow episode (Fig. 3, Interior drawer bottom of Fig. 1). Roberts died in 1957. In the late 1960s, the desk and bookcase was consigned to Jordan Marsh Department Store in Boston, Massachusetts, where it was featured in an advertisement in The Magazine Antiques (Fig. 4, Ad in The Magazine Antiques).2 It was purchased by Dr. and Mrs. Alfred Donovan of Lynnsfield, Massachusetts, where it remained until its rediscovery by Farmer. John McInnis Auctioneers sold the Donovan’s collection, including the desk and bookcase, at an on-site auction at the Donovan’s Massachusetts home on September 13 and 14, 2014. It was purchased and returned to the South, where it currently resides in a noted Virginia private collection.

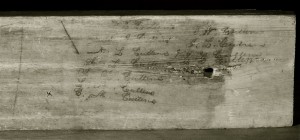

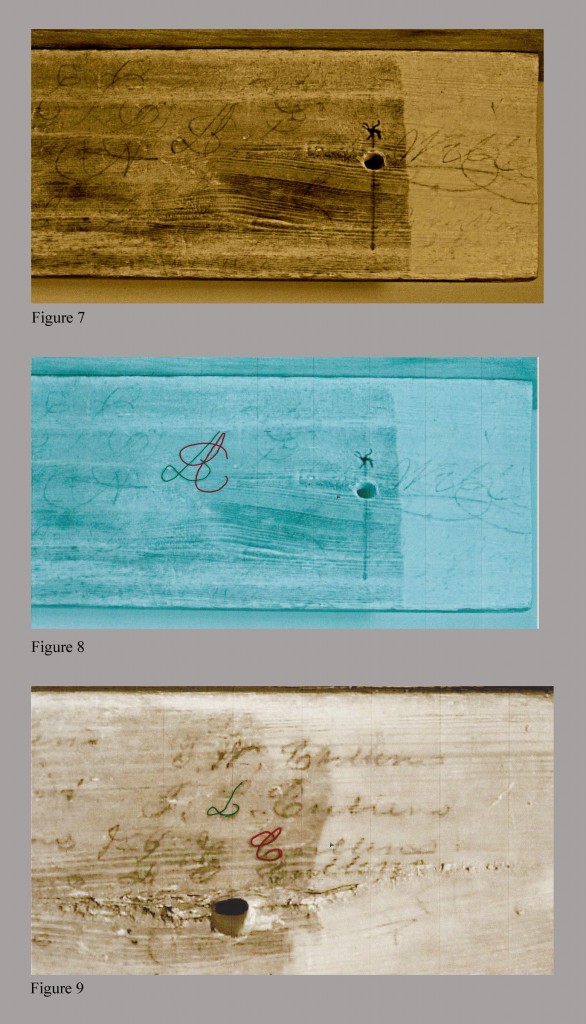

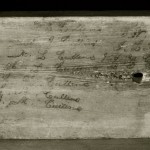

Upon its return to the South, the desk and bookcase’s new owners enlisted the aid of Tom Snyder, an expert in furniture restoration, to return the piece to its original appearance. During his examination of the piece, Snyder discovered writing on both fallboard supports. The writing extends to the back edge of each support, so had to have been applied at a time when the supports were removed from the desk. The writing on one of the supports is in two columns and proved to be the names of members of the Cullens family of Hertford County, North Carolina (Fig. 5, Writing on fallboard support of Fig. 1).

Hertford County is located in northeastern North Carolina and is bordered by Bertie County to the south, the home of the piece’s maker, William Seay. The second support contains a number of elaborately scripted letters, as well as two words, one of which is a first name.

Research has identified the series of names on the first fallboard support as members of a branch of the Cullens family who lived in Harrellsville, North Carolina, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Harrellsville is a small community located in southeastern Hertford County near the Chowan River. First settled in the early eighteenth century, the community was named Bethel until it was renamed Harrellsville in the middle of the nineteenth century.3 The top name in the left column on the support is W. E. Cullens. William Edward Cullens, the son of Nathan L. Cullens and his wife, Sarah, was born on February 16, 1861.4 He and his siblings grew up on their parent’s farm, located one mile southeast of Harrellsville. Their home still stands. Sarah inherited the land from her parents, William and Parthenia Scull Lassiter. The Lassiters built the house on their 592-acre plantation that was later occupied by Nathan and Sarah (Fig. 6, Home of Nathan and Sarah Cullens).

W. E. Cullens served as a Hertford County Commissioner until he resigned in 1894 upon his election as the Sheriff of Hertford County. He served as Sheriff until 1896. He was again elected as a county commissioner in 1904 and 1906. He also operated a mercantile in Harrellsville.5

The second name in the support’s first column is J. A. Cullens. James A. Cullens, William’s younger sister, despite her male name, was born in 1863. The third name, N. L. Cullens, Jr., represents William’s brother and his father’s namesake, Nathan L. Cullens, Jr. Nathan was born in 1865. The next name in the list, J. L. Cullens, probably represents Jacob Cullens, William’s brother who was born in 1867. His name is followed by the name of his sibling, J. H. Cullens. Joseph H. Cullens was born in 1871. The next name in the first column on the support is L. P. Cullens. William’s sister, Lula P. Cullens, was born in 1874. The last name in the column, C. M. Cullens, stands for Charles M. Cullens, William’s brother who was born in 1878.

The first name in the second column, T. W. Cullens, is not found in available records. The Hertford County census of 1880 does list an unnamed, three month old son in the home of Nathan and Sarah Cullens.6 This could have been T. W., who may not have survived infancy. The next two names in the second column are J. L. Cullens and J. H. Cullens. These names could be repeated from the first column. One of these names could also represent James D. Cullens, William’s brother, who was born in 1883.7 James survived to adulthood and married. The writer may have miswritten James’ middle initial, while the second of these two names may represent another child who did not survive infancy. Considering this is a reuse of the given name, James, by Nathan and Sarah, here for a son, the daughter James A., listed in the first column, may have died after the 1880 census. The fourth and last name in the second column is difficult to read.

The first question becomes who wrote the names of the Cullens children on the fallboard support? The writer was likely in possession of the desk and bookcase, so this knowledge is helpful in placing the piece in a specific Cullens home in the late nineteenth century, approximately a century after William Seay constructed it. The first and most obvious candidates are Nathan L. Cullens, Sr. and his wife, Sarah, the parents of the children. Sarah’s handwriting has not been located in surviving records. It seems unlikely Sarah would have neglected to list her son James D., and a mother certainly would not have listed her son with the wrong middle initial. The 1900 census lists James D. in Nathan and Sarah’s household.8 Nathan apparently died before the 1910 census. That year, Sarah was listed in the household of James D. and his wife, Gertrude.9 Nathan’s signature does survive in documents contained in the Chowan County estate of his father, Jacob Cullens, and in numerous documents found in the Hertford County estate of William Lassiter, Sarah’s father.10 Nathan’s handwriting is not consistent with the handwriting found on the fallboard support. Nathan’s “N”, “L”, and “C” all differ from those letters found on the fallboard support.

The next Cullens to consider as the potential writer of the names on the fallboard support is the oldest son, William E. Cullens. In his position as Sheriff of Hertford County from 1894 through 1896, he was called upon to sign court papers, including returns on subpoenas. His signature is present in several Hertford County estates of the period, and it is completely different from the writing on the fallboard support. The signatures of several of William’s siblings are also available for comparison to the list found on the fallboard support. In 1910, a lawsuit was filed by Charles M., Joseph H., Jacob, Lula P., and James D. against William over the division of Nathan and Sarah’s land. The case, eventually determined by the North Carolina Supreme Court, was decided in favor of the siblings and against William. William was required to make payments to his siblings. The siblings’ signatures are preserved on documents acknowledging their receipt of those payments.11 None of these signatures match the writing on the fallboard support.

The answer to the question of who wrote the names on the first fallboard support is most likely answered by writing found on the second fallboard support (Fig. 7, Writing on second fallboard support of Fig. 1). Of the two words to the rear of the second support, only the top word can be deciphered. The word is “Willie”. A small portion of the rear edge of the support has been cut off after the writing was applied, slightly truncating the flourish that accompanies “Willie”. This probably occurred during Mr. Goodwin’s restoration of the piece in the 1920s and was necessitated by shrinkage of the case. This word is an important clue to the identity of the Cullens household that actually possessed the desk and bookcase. On December 19, 1889, William E. Cullens married Willie Pauline Powell. Willie was born on July 1, 1871, so she was 18 at the time of her marriage.12 They lived on the south side of Main Street in Harrellsville.13 This is the most likely location for the desk and bookcase in the late nineteenth century. It also appears Willie was practicing a flourishing style of writing on the support that bears her name. The formation of these letters compares favorably to the letters used to create the names of her husband and his siblings on the first fallboard support. This is most apparent in the flourish to the left of “Willie”. What at first appears to be one letter is actually two, a “C” superimposed over an “L” (Fig. 8, Detail of Fig. 7). Both letters are consistent with the “Cs” and “Ls” found in the Cullens names written on the first fallboard support (Fig. 9, Detail of Fig. 5).

The evidence presented to this point indicates that the desk and bookcase was located in the home of William E. and Willie Cullens on a lot purchased by the Cullens in October 1890, on the south side of Main Street in Harrellsville.14 The next question becomes whether there is any evidence indicating where the desk and bookcase might have been before the Cullens’ possession. It was constructed by William Seay in his cabinet shop, which was located on Seay’s plantation southeast of the present community of Roxobel. Roxobel is located in northwestern Bertie County near the Roanoke River. Seay began constructing houses and undoubtedly some furniture in the 1770s and continued until his death in 1812. Seay built some of the most extravagant furniture ever created in North Carolina beginning about 1790, when he received a large furniture commission from wealthy Halifax County planter, Whitmell Hill. Seay’s patrons consisted of the wealthy planter families on both sides of the Roanoke River within an approximate 25-mile radius of Roxobel. Harrellsville is located in southeastern Hertford County. There is no known evidence that Seay’s patronage extended that far from his plantation near Roxobel or that he conducted business with planters along the Chowan River. It is unlikely that the desk and bookcase was originally owned in the Harrellsville area. Therefore, it would have been transported by a prior owner to the Harrellsville area before it came into the possession of the William E. Cullens family in the late nineteenth century.

An examination of the lineage of both William E. Cullens and his wife, Willie Pauline Powell, offers insight into the most likely path taken by the desk and bookcase as it made its way from Mr. Seay’s cabinet shop to the Cullens household in Harrellsville. William E. Cullens’ father, Nathan Cullens, was the son of Jacob and Arita Cullens of Chowan County. Nathan is listed in Jacob’s home in the 1850 Chowan County census.15 Chowan County is located on the east side of the Chowan River and across the river from Harrellsville, and therefore is even further away from William Seay’s sphere of trade. Jacob was the grandson of an earlier Nathan Cullens and his wife, Christian Docton, both also of Chowan County.16 In 1779, this Nathan purchased 140 acres from a member of the Powell family north of the Lewiston-Woodville area of Bertie County.17 This land is located about five miles east of Roxobel and is well within the area of known Seay customers. While the purchaser never moved to the land from Chowan County, the tract was inherited by the earlier Nathan’s children, who sold it back to the Powell Family after these Cullens had relocated to Georgia in 1798.18 There is no evidence of any connection between these Cullens and William Seay. It also is not known if any of this branch of the Cullens family resided on this land, although one of Nathan and Christian’s children, Fredrick, appears to have been a Bertie County resident before relocating to Georgia. It is safe to say that the vast majority of the Cullens line were, and remained, Chowan County residents. Even considering the earlier ownership of land in Bertie County, it is unlikely that the desk and bookcase descended in or was owned by members of the Cullens family before it entered into the household of W. E. and Willie Cullens.

W. E. Cullens’ mother, Sarah, was the daughter of William Lassiter and his wife, Parthenia Scull.19 Both the Lassiters and the Sculls had resided in the Harrellsville area for several generations and had no know relationship with William Seay or the lands along the Roanoke River where Seay patrons resided. Again, there is no known indication that the desk and bookcase was likely to have been owned by or descended in those families.

With the W. E. Cullens lines unlikely sources for the descent or ownership of the desk and bookcase, next we examine the family of his wife, Willie Pauline Powell. Willie’s parents were William Henry Powell and his wife, Augustine Parker. Augustine was the daughter of David Parker and the granddaughter of Silas Parker.20 The Parkers lived near the Mapleton community in central Hertford County, located between Winton and Murfreesboro.21 There is no evidence that William Seay worked in this section of Hertford County, and there are no know connections between Seay and this branch of the Parker family. So another line and the area where they resided effectively can be eliminated as a likely source of ownership or possession of the desk and bookcase.

Willie’s father, William Henry Powell, and his family, however, are another matter. Beginning in the 1720s, this branch of the Powell family lived in southwestern Hertford County just five miles north of William Seay’s cabinet shop. Along with the Norfleets and the Hills, the Powells were among the families most closely connected to Seay. Seay built a house for Cadar Powell around 1798.22 Evidence indicates that Cadar’s brother, Jesse Powell, apprenticed in Seay’s shop from about 1787 to 1793. Jesse later served as a journeyman house joiner during which time he acquired the means to purchase a substantial plantation in neighboring Halifax County. The house Jesse built for himself in Halifax exhibits decorative elements Jesse learned in Seay’s shop.23 Another of Cadar’s brothers, Willis Powell, is believed to be the original owner of a Seay corner cupboard with decorative Masonic details. This privately owned corner cupboard was documented and photographed by MESDA. Willie Cullens’ father, William Henry Powell, was the grandson of this Willis Powell. William Henry Powell is known to have owned the Seay Masonic corner cupboard, and it descended through the line of Willie’s first cousin.24 Willis Powell’s wife, Celia Averitt, inherited land north of the Lewiston-Woodville area.25 Willis and his descendants lived in this area, which is located five miles east of Seay’s cabinet shop.

Absent a strong history of descent, it is often difficult to determine the exact line through which of a piece of furniture passed in a family. Some of the inventory records of Willie’s line of the Powell family no longer exist, while others list property by room rather than individually. Willis Powell’s estate sale of 1808 does note that a desk was purchased by his widow, Celia, along with two beds and furniture and a bofat. These were four of the first five lots sold in the sale and were purchased by the widow for matching nominal sums, a concession shown widows in other Bertie County estate sales. An item termed a “desk and cover” was the next item auctioned. It sold out of the Powell family for a competitive and high price.26 When the purchaser died a number of years later, this item was not listed in his estate.27 It cannot be determined from available records whether the “desk and cover” was given to a relative of the purchaser, repurchased by a member of the Powell family, or was bought by another individual. It is also not known if the desk purchased by the widow was in fact a desk and bookcase, which sold for an obviously reduced price. So evidence that might show whether the Cullens desk and bookcase descended directly through the Powell family, descended in one of Willie’s maternal lines such as the neighboring Lee or Averitt families, or was purchased by a family member at a neighbor’s estate sale, is inconclusive. However, considering that all these families lived in an area in close proximity to the Seay cabinet shop, the extended Powell line is by far the most likely path of descent to the W. E. Cullens household.

Even more compelling evidence of a Powell line of descent is found from an examination of potential ways a monumental William Seay desk and bookcase would be transported in Harrellsville. Although this is not an often seen pattern of migration, a number of Willie Cullens’ close Powell relatives migrated from the Lewiston-Woodville area of Bertie County, five miles from Seay’s shop, to Harrellsville in the late nineteenth century. Any one of them is a potential candidate to have transported the Seay desk and bookcase from the region an original owner would be expected to have resided to its eventual home with the Cullens. Harrellsville was a thriving nineteenth century community near the Chowan River. It contained a noted school, the Union Male Academy, whose graduates included two United States Consul Generals, as well as a number of attorneys and doctors.28 The land around Harrellsville was as rich and fertile as any along the Chowan or Roanoke Rivers. The most prominent landowning family in the area was the Sharp family, arriving in the 1720s and acquiring thousands of acres of productive farmland. Eulalia Powell, Willie’s older sister, married into the Sharp family. On November 11, 1876, she married Charles L. Sharp and moved from Lewiston-Woodville to her husband’s home in Harrellsville. After his death, she married his first cousin, Henry Clay Sharp, and lived at Evergreen plantation just east of Harrellsville.29 Willie’s uncle, James M. Powell, moved from Lewiston-Woodville to Harrellsville by 1880 and lived next door to the lot on Main Street that later became the home of W. E. and Willie Cullens.30 The Cullens lot was actually purchased from Eulalia and had been Sharp property. Mary Elizabeth Powell, James M. Powell’s sister, and therefore Willie Cullens’ aunt, married James Sharp, the brother of Eulalia’s first husband, Charles L. Sharp.31 When Willie’s mother, Augustine Powell, died in 1884, her inventory lists property at her house in Lewiston-Woodville, as well as a second listing of her property in Harrellsville.32 One can easily imagine a newly married couple such as William and Willie exploring her numerous relatives’ outbuildings in the area in search of very inexpensive out–of–style furniture to furnish their new home. This could well be the time that the feet of the desk and bookcase were removed to allow the piece to fit into their home while preserving its elaborate scrolled pediment. The necessity of cleaning a stored piece could also explain the need to remove the fallboard supports, allowing the opportunity to document a list of family members on a previously and future unseen surface. While this reclamation scenario is merely supposition, the likelihood of a member of Willie’s family being responsible for transporting the Cullens’ desk and bookcase to Harrellsville is compelling.

The Cullens desk and bookcase displays standard Seay construction features, adding further evidence of Seay’s personal involvement in the creation of the core furniture group produced in his shop (Fig. 10, Cullens desk and bookcase by William Seay).

As noted, prior to its purchase by Roberts in 1924 in Petersburg, the feet had been removed. The bottom of the case retains nail holes that once held the nails attaching triangular foot supports matching those found on other Seay case pieces. Blocks secured in this way are not likely to have been lost through normal use. They were probably removed purposely, along with the feet, when the piece was moved to a house with lower ceilings. While an unfortunate loss, it is the lesser of two evils considering the importance of the scrolled pediment. The desk’s drawer bottoms are set from front to back (Fig. 11, Drawer bottom of Fig 10).

These boards were probably taken from Seay’s stock of shiplap boards intended for house construction. A newly discovered Seay chest of drawers found in Windsor, North Carolina, contains drawer bottom boards that were finished as shiplap and had already received their decorative one-half inch bead. The desk portion of the Cullens desk and bookcase also exhibits the mortise and tenon framed drawer support system that mimics window frame construction used by house joiners of the period (Fig. 12, Drawer support system of Fig. 10).

William Seay was first and foremost a house joiner, and his use of a carpenter’s solution to a cabinetmaker’s need is perhaps the most distinctive feature of this furniture group.

There are also several distinctive decorative and structural features that may hint to the desk and bookcase’s place in the chronology of Seay furniture production. The bookcase doors contain standard Seay articulated arches in their upper rails, but no blind panels are present at the bottom of the doors (Fig. 13, Bookcase doors of Fig. 10).

Pinwheels are present in the roundels of the scrolled pediment, but both pinwheels contain at least one spoke set in the wrong direction (Fig. 14, Pinwheels of Fig. 10).

Note here in Fig. 14 that the upper portion of the finial appears to be replaced. Indeed, this is not the case. The finial is intact and was originally constructed in two pieces. The base of the pediment retains its original double band of lightwood inlay (Fig. 15, Pediment string inlay of Fig. 10).

On subsequent similar Seay pieces, there are only open double dados. It is unknown whether the other pieces originally had lightwood inlays that have been lost or were constructed only with open dados. Although one nail hole of unknown origin was found, there is no structural evidence of valences above the desk’s cubbyholes (Fig. 16, Desk interior of Fig. 10).

The pitch of the pediment sweeps upward at a lower angle than other Seay examples (See Fig. 10, compare to WH Cabinetmaker …, Figs. 5, 30 and 84). Further and most tellingly, while the tympanum of the pediment contains ebonized decorative vines matching other Seay examples, the decorative elements of this piece’s tympanum are not relief carved (See Fig. 13). This is the only known example built by Seay that is not relief carved and is the only known example of a bookcase with these decorative elements placed on a fall–front desk rather that a press with butler’s drawer.

Several arguments can be made for the subtle differences between the Cullens desk and bookcase and the WH group and Perry Tyler press and bookcase, including patron preference and cost considerations. However, a strong argument can be made that this desk and bookcase may well be the prototype for Seay’s WH series of 1790. Several factors, including the placement of the bookcase on a fall-front desk, the different pitch of the pediment, the inconsistent angle of the spokes in the pediment’s pinwheels, the lack of blind panels in the bookcase doors, and most importantly, the lack of relief carving in the bookcase’s pediment, seem to point more surely to this hypothesis than to other theories.

One final twist of fate will complete the presently know saga of the travels of the Cullens family desk and bookcase. After the purchase of their lot, William and Willie Cullens built a two-story house, which burned in 1928, only four years after Roberts’ purchase of the desk and bookcase in Petersburg. While the Cullens replaced their house with a bungalow in 1929 that still stands, if the desk and bookcase had not been sold, it undoubtedly would have been lost in the fire. The history on the drawer bottom (see Fig. 3) does not indicate from whom Roberts purchased the desk and bookcase. He probably bought it from a local Petersburg dealer who like many early southern dealers picked the countryside for stock. Fortunately, this important piece of southern craftsmanship now safely resides in its new home, where it has revealed some, but certainly not all, of it secrets.

The authors wish to thank Ken Farmer, Carolyn and Mike McNamara, and Tom Snyder for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

Published on: Jan 12, 2016

Endnotes:

- Kenneth L. Roberts, Antiquamania, Doubleday, Doran, and Company, 1928, pp. 19 and 37-42.

- MESDA Research File NCE-8-57/NCE-74-29.

- Thomas C. Parramore, The History of Harrellsville, Pierce Printing Co., Inc., Ahoskie, N.C., No Date, pp. 40-41.

- Benjamin B. Winborne, The Colonial and State History of Hertford County, North Carolina, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, M.D., 1976, p. 294.

- Ibid, pp. 279 and 294.

- Hertford County Census of 1880.

- Hertford County Census of 1900.

- Ibid.

- Hertford County Census of 1910.

- North Carolina State Archives, Hertford County Estate Records, William Lassiter Estate.

- Archives, Hertford County Estate Records, Nathan Cullens Estate.

- Sally’s Family Place, Helen Cotton (Powell).

- National Register Application, Harrellsville Historic District, Penne Smith, consultant, 1995, p. 17.

- Hertford County Deed Book S, p. 94.

- Chowan County Census of 1850.

- Sally’s, Abner Eason and Rachel Docton.

- Bertie County Deed Book M, p. 457.

- Bertie County Deed Book R, p. 498.

- Winborne, p. 294.

- Hertford County Census of 1850 and Sharp Family History Blog by Bill Ives, Silas Parker, Part One, April 29, 2007.

- Winborne, p. 298.

- Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved, Legacy Ink Publishing, 2009, pp. 95-99.

- Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor, “Original Owners of Historic Hope Foundation’s China Press”, EHCNC.ORG, April 11, 2014.

- Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 220-221 and MESDA Research File S-2097.

- Bertie County Deed Book U, p. 26.

- Archives, Bertie County Estate Records, Willis Powell Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Estate Records, Luke Raby Estate.

- Parramore, pp. 38-39.

- Sally’s, Starkey Sharp.

- National Register, pp. 17-18.

- Sally’s, Starkey Sharp.

- Archives, Bertie County Estate Records, Augustine Powell.