His Life and Possessions

By Bill Beck

To begin, who was Hugh Blair Grigsby? He was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on 22 November 1806 to Benjamin Porter Grigsby (1770-1810) and Elizabeth (McPherson) Grigsby (1778-1860). Hugh Blair Grigsby studied law at Yale in the early 1820s; however, he never practiced the profession even though qualified to do so. Instead, he became a noted scholar, historian, author, statesman, and planter. Grigsby represented Norfolk as a member of the Virginia (Constitutional) Convention of 1829-30. His writings on the Virginia Conventions of 1776, 1788, and 1829-1830 are well known.

On November 19, 1840, Grigsby married Mary Venable Carrington, the daughter of Colonel Clement Carrington of Edgehill plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia, and moved from Norfolk to Edgehill. He spent his life at Edgehill indulged in agricultural excellence.

In addition to agriculture, Grigsby was keenly interested in education and history. He maintained a massive library covering diverse subjects. In 1850, he was appointed to the Board of Visitors at the College of William and Mary. Five years later, the College of William and Mary honored him with the degree of Doctor of Laws. Grigsby was elected to the presidency of the Virginia Historical Society in 1870, and he was elected Chancellor of the College of William and Mary in 1871.

Hugh Blair Grigsby and his wife, Mary, had two children, Hugh Carrington Grigsby (1856-1909) and Mary Blair (Grigsby) Galt (1860-1916). Grigsby died at Edgehill on 26 April 1881. Mary died in 1894. Grigsby, Mary, Hugh, and Mary Blair are all buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Norfolk (Figs. 1-6, Grigsby gravestones).

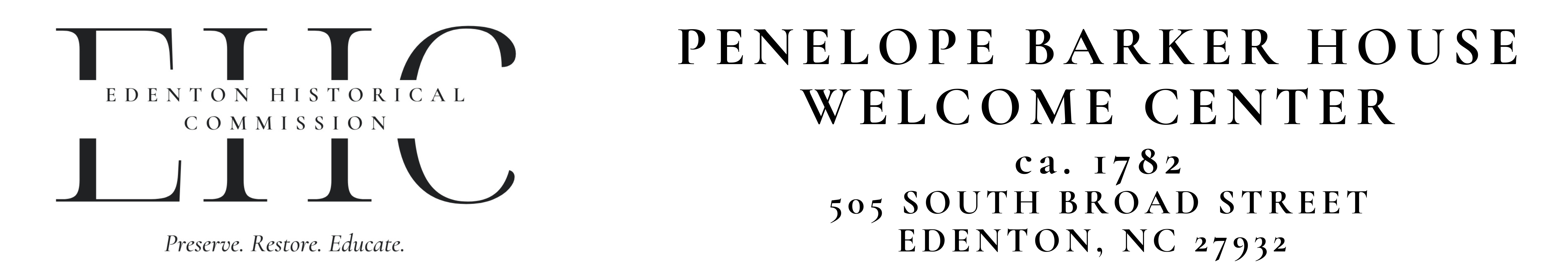

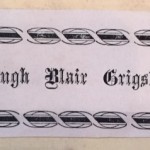

Some years ago, I was introduced to a very nice fellow who told me that he was the great-great-grandson of Hugh Blair Grigsby. He seemed pleasantly surprised that I immediately recognized the name, but of course I did. I already had a copy of Grigsby’s “Virginia Convention of 1776” on my shelf (Fig. 7, Virginia Convention of 1776 copy) as well as a reference work on the Chief Justices of the United States that bears Grigsby’s bookplate (Figs. 8 & 9, Chief Justices book & Grigsby bookplate).

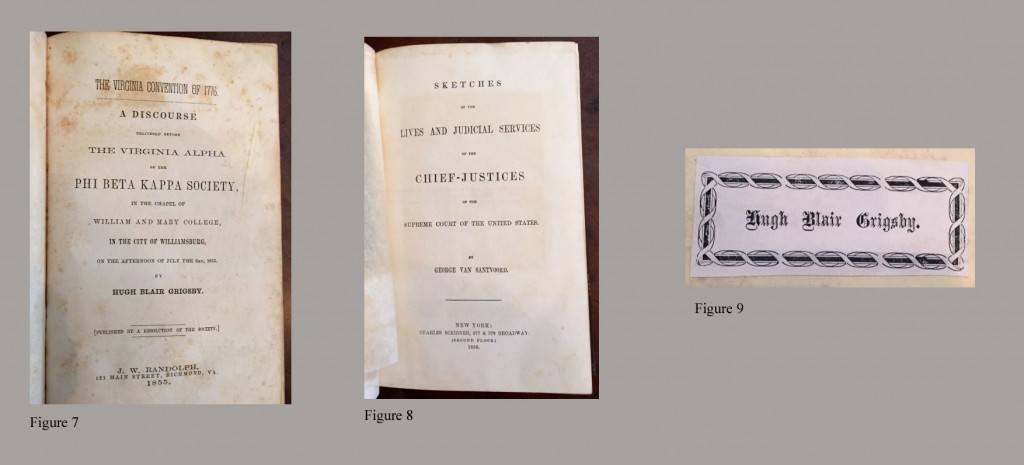

After a bit of Virginia history talk, I learned that my new acquaintance was the last of his line and was interested in disposing of some of the family possessions that he had inherited. Over the course of several years, I purchased three items that had descended in his family from Hugh Blair Grigsby. In some ways, the most exciting might be a very fine cased pair of pistols in their original box with Grigsby’s name engraved on the brass-bale handle (Figs. 10-15, Grigsby pistols). Samuel Evans of Cambridge, England, made this set of pistols around 1835. Cased pairs of pistols were not uncommon in Virginia in the late eighteenth-early nineteenth centuries. Wealthy Norfolk merchant and mayor, Moses Myers, owned a fine set of ca. 1790s pistols by London maker, Durs Egg. The fitted case bears the label of Joseph Spratley, Norfolk gunsmith and dealer. By family tradition, the Myers pair of pistols were used in the Barron-Decatur duel on 22 March 1820 where U. S. Navy hero, Stephen Decatur, was mortally wounded by disgraced fellow officer, James Barron. These pistols remain in the Myers House collection in Norfolk.

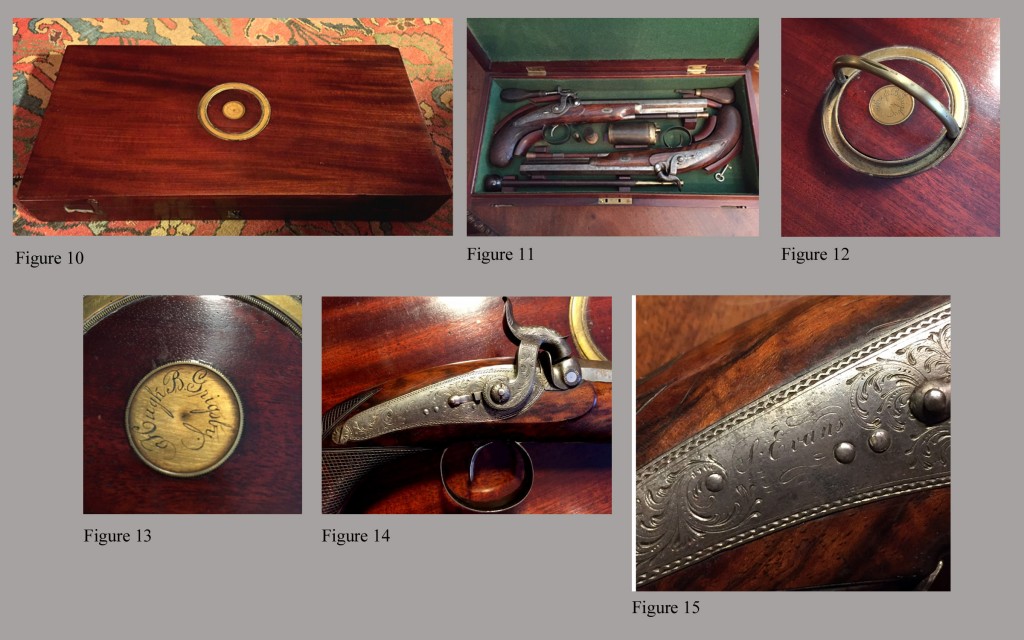

I also purchased an unusually large, elaborately fitted, brass-bound desk box (Figs. 16 & 17, Grigsby desk) that contained a seventeenth-century English prayer book inscribed “H. B. Grigsby, Norfolk, 1822” and an early quill pen (Fig. 18, Prayer book and quill pen). This burl-wood desk appears to be of English origin but very well could be China Trade. It dates around the middle of the nineteenth century. The early prayer book is but a tiny sample from Grigsby’s extensive and diverse library. Its importance lies in Grigsby ownership and his signature.

The piece of most interest for furniture historians is the large mahogany armchair (Fig. 19, Armchair) that my friend said “Family tradition has it that Hugh Blair Grigsby had the chair made for him to accommodate his great weight in older age.” The chair is commodious but not abnormally large for a “Chippendale” armchair. He also told me that “It was said to have been made by a former slave” a slight variation on the story that we so often hear with old Virginia family furniture. Most likely, neither family tradition is credible.

On an unrelated visit to my home, furniture scholars, Jim Melchor and Tom Newbern, examined the chair after I told them about the Grigsby ownership. They both agreed that the chair had a strong British appearance and was of an eighteenth-century style that predated Hugh Blair Grigsby. Based on their assessment of the construction details, they felt that while probably British, it could possibly have been made in eighteenth-century Norfolk. The seat rails are heavily constructed and do not incorporate glue blocks (Figs. 20 & 21, Armchair seat rails). Likewise, the stretchers are equally heavily constructed (Fig. 22, Armchair stretchers). These are construction traits observed in Norfolk chairs (Figs. 23-25, Norfolk chair and construction details). In fact, most Norfolk furniture is sturdily constructed throughout. Also note the beveled, inside, lower edge of the rear seat rails on both the Grigsby armchair and the known Norfolk chair (see Figs. 20 & 25).

The arms of the Grigsby chair are its most striking feature (Figs. 26-28, Armchair arms). Indeed, these vernacular arms are quite unusual, and they are decorative-detail signatures of its maker.

The chair’s slip seat appears original, and it is constructed of a pine (Fig. 29, Armchair slip seat). I had the wood of the slip seat tested. The result was Pinus sp., generic red pine. P. resinosa, North American red pine, and P. sylvestris, British red pine, look alike microscopically. In some instances, but not always, the two can be distinguished. Unfortunately, such was not the case with the Grigsby slip-seat sample. Melchor and Newbern have found white pine, red pine, and spruce in a number of Norfolk, Norfolk area, and northeastern North Carolina pieces, frequently mixed with local woods. They have also documented references to “white pine” and “other northern woods” being shipped into and used in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. There is absolutely no question that white pine, red pine, and spruce were imported into Virginia from New England and used by local cabinetmakers. Consequently, the finding of red pine in the Grigsby slip seat does not definitively indicate British or Norfolk origin. It could be either.

It really does not matter whether the chair was made in Norfolk or Great Britain. What is important is this chair belonged to Hugh Blair Grigsby and has an eastern Virginia history. Since the chair predates Grigsby, the remaining question is where did he get such an old, outdated chair and why would he want it? The most likely answer is he inherited it from his father, it had some sentimental value, and it was and still is comfortable.

Hugh Blair Grigsby was a notable figure in Virginia history. To be able to keep some of his possessions together, to discuss them here, to share them with others, and to be the caretaker of them for future generations is an honor.

Published on: Aug 6, 2015

Bibliography/References:

Virginia Historical Society

Personal communications with Jim Melchor

Personal communications with Tom Newbern

Photo Credits:

Figs. 1-6 & 23-25, Courtesy of Jim Melchor