Examination Methodology

By Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

Great Aunt Maude is a pillar of the community. Additionally, she is the custodian of family lore and a few family facts that are actually true. Aunt Maude’s favorite thing on this earth is her prized mahogany table placed lovingly and safely in the far corner of her parlor (Fig. 1, Aunt Maude’s table). She relishes the opportunity to regale friends and family alike with the proud history of this heirloom. The table, according to Aunt Maude, descended directly through her family from its first owner. He was a member of the first settlement at Jamestown and was also a distant relative of the British Royal Family.

Most families have an Aunt Maude as well as a prized piece of family furniture whose true origin probably was lost years ago. So how can you separate fact from fiction? How can you determine the true history and age of your family heirloom?

The methodology used by the authors for an examination of a prized piece of antique furniture is based on their former professions. One was a scientist and one was a trial lawyer. Both fields utilize the same basic thought processes. They both involve an analytical examination of the facts, attention to details, and the necessity to consider all the available evidence, not just evidence favorable to a particular point of view. In our former worlds, failure to follow these steps could result in the loss of an important case or the failure of a shoreline structure. These same thought processes also work well for an examination of a piece of antique furniture, and luckily, the consequences of a lapse are not nearly as dire.

Our good friend John Bivins was one of the best at the examination and analysis of a piece of furniture. His powers of observation were well respected, and his ability to document his findings in a manner that was both informative and easily understood made his writings a pleasure to read. He is greatly missed. Bivins always said the first step in the analysis of any valued object was to look at it and visualize generally what it is and is not. An example would be a chest of drawers with four graduated drawers, constructed of walnut, with straight bracket feet, a coved bed molding, and a top with integral molding. That seemed fairly obvious, but his next step was profound. Bivins then stressed the importance of putting everything you had just seen totally out of your mind until you had completed a through examination of the object in question. That examination entailed looking at the details of the object without any preconceived ideas. Bivins understood the danger of the human mind’s propensity to assume and, therefore turn an objective analysis into a self-fulfilling prophecy, or as another friend describes it, going down the rabbit hole. If you do not discipline yourself to look at each aspect of a piece of furniture separate and apart from your initial observations, you might not be able to resist the temptation to make the facts fit the form. This is sound advice that is essential to the unbiased assessment of any piece of decorative art.

In the world of law, there are two types of evidence that are presented in a courtroom to prove a case. The first is direct evidence, which is essentially eyewitness testimony. If direct evidence is relevant to your determination of when and by whom your valued antique was made, it is, unfortunately, not as old as you might wish, as the observer (eyewitness) is still alive. The second type of evidence is circumstantial evidence. This evidence is defined as a series of facts that point unerringly to a person’s guilt, or in this case to the origins of the object in question. Circumstantial evidence is likened to links in a chain. Each piece of evidence is a link, and all must be examined. However, after examining each link, if you find that each separate link points to the same conclusion, and there are no breaks in the chain, then in a courtroom you would be instructed by the judge to give circumstantial evidence the same weight that you would give direct evidence. The theory of circumstantial evidence is based on probability. If one piece of evidence or link points to a conclusion, you might find that to be interesting. If two point to the same conclusion, that might be a pattern, but if four, five, or six separate pieces of evidence all point to the same conclusion, with no believable pieces of evidence indicating otherwise, then based on the highly unlikely probability of that happening by chance, it becomes very compelling. The odds of picking one or two numbers of a lottery are not that great, but the odds of picking all six numbers on your card for a particular drawing become astronomical. Therefore, if you find a piece of furniture whose woods, case, drawer, and foot construction, decorative features, and provenance all separately indicate the same point of origin, with no credible evidence pointing otherwise, it is very likely that the piece was constructed in that location. If this process is accepted by our society to determine conflicts between citizens or to restrict the freedoms of an individual accused of a crime, it should suffice to determine the origins of a piece of furniture.

A good example of the potential pitfalls of not following this methodology can be seen in an evaluation of a highly carved furniture group now clearly shown to have been made in Edenton, North Carolina, in the second half of the 18th century. Bivins first discussed this group in his seminal work, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820 (FCNC). He presented various factors, or links in the chain, that created a compelling case for his attribution of the group to Edenton.1 The most distinctive decorative feature found on some of the examples from this group is a sharp blade-like rear talon on the rear of the ball and claw feet. In Edenton Furniture and Culture…, we discussed the influence of Scottish and Irish merchants who settled in Norfolk as a result of the lucrative tobacco trade between their home countries and the Southern colonies before the American Revolution.2 Norfolk, by far the most dominant port in Virginia or North Carolina during the period, exhibited like influence on southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, including Edenton. This influence could be seen in the decorative arts of the region, so it should be no surprise that features found on Edenton furniture would also be seen on Norfolk furniture. A Norfolk version of the blade-like talon on the rear of ball and claw feet was recently published.3 Once again, attention to detail is essential. The Norfolk version of the sharp rear talon exhibits a smooth transition from the lower leg to the talon, while the sharp rear talons found on Edenton examples display an indention at the same location. The strength of this feature to distinguish between examples made in the two ports will be determined as more Norfolk examples are discovered, but it is a point of distinction that should be noted.

More importantly, two factors or links that have to be ignored to propose a Norfolk attribution for examples in the Edenton group exhibiting ball and claw feet with blade-like rear talons are provenance and structural details. All the examples of the Edenton group with strong provenances or recovery histories were found within twenty miles of Edenton, thus, not in Virginia. As we detailed in Edenton Furniture and Culture…, a carved writing table from the group was found in eastern Bertie County across the Albemarle Sound from Edenton. A pair of carved card tables from this group descended in the family of Wiley Jones of the town of Halifax. Jones served as an agent for Lord Granville, whose headquarters for Granville District land transactions was located in the Cupola House in Edenton. So Jones had ample business dealings with merchants and craftsmen in Edenton. An Edenton group six-leg ball and claw foot dining table descended in the Webb family, who lived just east of Edenton near the Chowan-Perquimans county line. One of four armchairs known from this group was owned by the Cox family in Edenton in the early 19th century. A second example was found in the town of Hertford, located 14 miles east of Edenton. Other examples have similar family and recovery histories.4 A construction feature that distinguishes the Edenton group from Norfolk examples is the hinge joint connecting a table’s fixed rail to its swing rail (Fig. 2, Side view of hinge joint on Edenton table) (Fig. 3, Bottom view of hinge joint on Edenton table). The end of the fixed rail is square as it meets the end of the swing rail. The end of the swing rail is concave as it meets the fixed rail. This is a feature also found on drop leaf tables made in Chowan and neighboring Perquimans counties (See FCNC, Fig. 5.57C). Edenton examples are distinguished by a notch placed on the rear face of the fixed hinge rail to catch the radius of the swing rail as a 90-degree stop (see Fig. 3). Neither the Perquimans nor the Edenton versions of this hinge assemble are known in Virginia. These two important links in the chain cannot be ignored when properly analyzing this important furniture group. When they are added to other evidentiary links, including unifying decorative features such as foot webbing, toes and toe nails of ball and claw feet, locally used secondary woods, including yellow pine, poplar, cypress, and beech, strong Scottish and Irish decorative influence, and other unifying decorative and construction features, the group’s origins in Edenton become evident. This example should serve as a cautionary tale of the danger of considering only those factors that are favorable to your preconceived conclusion, as opposed to the conclusion that is reached if one considers all the evidence.

The examination of the Edenton group details a number of the factors or links that should be considered when examining any piece of furniture. As stated above, primary and secondary woods are essential factors to consider. Is the primary wood mahogany, walnut, or cherry? Furniture constructed in southeastern Virginia or northeastern North Carolina often contain a number of different local secondary woods, including yellow pine, poplar, cypress, red and white cedar, and occasionally beech and gum, to name a few. Northern woods, especially those shipped from the Piscataqua region of New England, are found in limited quantities in furniture made in Southern ports such as Norfolk and Charleston from the second quarter of the 18th century. Their use increased in the late 18th and the early 19th centuries. With the opening of the Dismal Swamp Canal in the early 19th century, these northern woods can also be found in furniture constructed in inland North Carolina ports such as Edenton. Microanalysis has shown the use of white pine and even spruce in furniture made in Edenton in the first years of the 19th century. Microanalysis is the safest course to follow when attempting to identify secondary woods, although some often–used secondary woods, such as yellow pine, poplar, and cypress can usually be identified by wood grain, by hardness, and in the case of cypress that is found is a protected area, by smell.

The construction of a piece of furniture is another important factor or link to be considered as you attempt to discover its origins. Are dust boards set behind a chest’s drawer blades, or do you simply find drawer runners? Are the dust boards the full depth of the case? Are they the full thickness of the drawer blades, or are they thinner and supported by wedges or strips of wood? Are the drawer runners dadoed or dovetailed into the case sides or simply nailed into position? An examination of drawer construction of chests and tables, too, is informative. How is the drawer bottom attached to the drawer front, sides, and back? It may be beveled along its front and side edges and set in dadoes run in the drawer front and sides, and flush nailed to the drawer back. Drawer bottoms may be set in rabbets run along the bottom of the drawer fronts, sides, and occasionally backs. This feature is often found on the drawers of 18th century Norfolk furniture and furniture constructed in the Roanoke River Basin in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The form and shaping of drawer glue blocks, if present at all, may also hint to the area of the piece’s place of origin. Cabinetmakers were often consistent in shaping dovetails while constructing drawers and joining case sides to case tops and bottoms. If no dovetails were used to construct the case drawers, and the drawer sides are nailed to the drawer front and back, you may be looking at the work of a house joiner or carpenter rather than a cabinetmaker. Another sign your piece of furniture may have been made by a house joiner is a lack of the use of glue to attach veneers or drawer or foot blocking. There are a number of books and articles available with which to compare your examples. However, again, construction alone is not determinative and is only a single link to be weighed with all other evidence.

Other factors or links to consider include the type of nails used in the case and drawer construction. Did the cabinetmaker use wrought rose, L-, or T-head nails, or do you find cut nails, which first came into use in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the mid 1790’s? If you see modern wire nails as a part of your furniture’s original construction, then it can date no earlier than the 1870’s. It is important to remember, however, that while the form of the nail is useful to determine the earliest date a piece may have been built, earlier style nails were often used on later pieces, such as the use of wrought nails during the period cut nails were readily available.

Provenance and recovery history are other important factors to consider when examining a piece of furniture. Caution should be applied, however, as there can be a great deal of variation in the strength of the evidence of the piece’s descent through the owner’s family. More weight can be given when a pattern of descent or recovery is shown throughout a related furniture group, such as the previously discussed Edenton group.

Decorative details, including inlay patterns, carved elements, and foot patterns and blocking are also important factors to consider, but remember, these same elements may have been used elsewhere, and no one or two links should be singled out as determinative. You must take the time to gather and consider all the available evidence. If you view any of these individual factors as favorable or unfavorable as you proceed through your analysis, you have probably violated Bivins’ first rule and are already well down your own rabbit hole.

One often overlooked, and more often ignored, piece of evidence that should be considered along with all other facts when examining a piece of furniture, is writing or marks. These include signatures, construction marks or notations, scribbles, instructions, or drawings, to name a few. The vast majority of marks are just illegible or random man-made marks, wood grains, or wood imperfections. It is very rare to find writing on a piece of furniture that can be read as one reads words in a book. Even this rare occurrence should be examined in the same way as any other piece of evidence. A cautionary tale involves a circa 1810 sideboard (Fig. 4, Sideboard). Visually, it was a form often constructed in Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia, in the first two decades of the 19th century, although it was also a popular form in Philadelphia and elsewhere. An examination of other factors or links, including secondary woods of yellow pine, white pine, and poplar, pointed to an urban southern origin. This sideboard, however, contains that rare exception to the rule, an easily read signature. Written boldly in chalk under the top of the case was “Thomas Reynolds Warrenton”. This fact was in keeping with other factors, as there is documentation that at one time Reynolds was probably in Petersburg before arriving in Warrenton, North Carolina, in 1804.5 There was one small problem with the signature, however. When you blew on the writing, fresh chalk dust filled the air. The signature, despite how smoothly it fit other links, was not period but had been placed on the sideboard by someone knowledgeable in regional furniture forms and history. What the forger of this signature missed, however, was a period inscription in graphite on the interior surface of the backboard of the case that read “Thos C___dall, R___mond”. A second inscription, also in graphite, was found under a drawer that read “Crandall and Allen”.

Thomas Crandall was a Richmond cabinetmaker. He also operated a shop in Lynchburg, Virginia, from 1813 until 1817, at which time he returned to Richmond.6 While in Lynchburg, he took Francis Allen as an apprentice.7 These period inscriptions offer evidence that Allen may have traveled to Richmond with Crandall upon his return. So after this and all other separate bits of evidence were examined and considered, what could have been misinterpreted as an important signed sideboard made in Warrenton was actually found to be an important Richmond example. Each piece of evidence or link must be carefully examined and then compared to all other evidence before a possible conclusion should be reached.

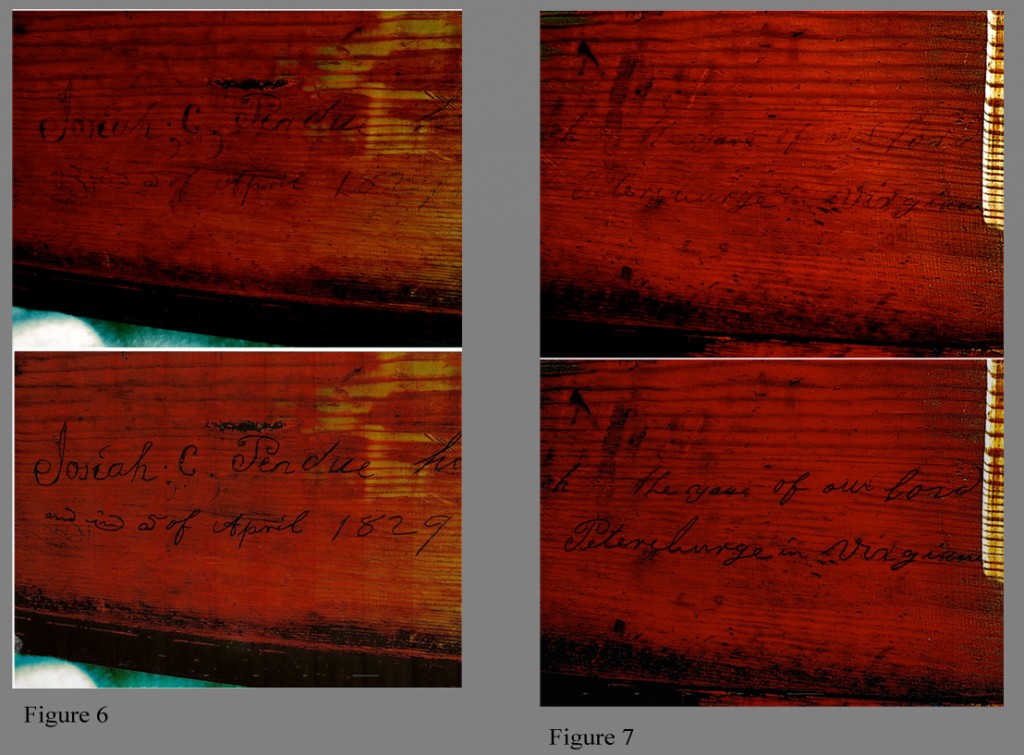

Another example of the importance of considering writing or marks on furniture along with all other links is found on a circa 1825 chest of drawers (Fig. 5, Chest of drawers). Its appearance, decorative features, and yellow pine secondary wood seem to point to Norfolk as its place of origin. A number of other examples, many with local histories, have been found in the Norfolk area. Two full lines of writing could be seen on the back of one of the chest’s drawers but the writing could not be read. A process that can sometimes aid in deciphering marks such as these is as follows. First, determine under what conditions the marks are most visible. It may be in full sunlight or in a shaded area. Graphite can often be enhanced by the use of a red-tinted light in a dark room, while a light blue light often enhances chalk inscriptions. Once the best conditions are established, do not try to read what is written. Instead, just follow the marks on the wood. It is helpful at this point to mimic the marks on a piece of paper as you follow them with your eyes. This at least creates a rough facsimile on the paper free of any imperfections or distorting wood grains in the wood itself. Now determine if the marks on the wood, while referencing the paper facsimile, form letters and the letters form words. The result is usually that the marks still cannot be deciphered, but sometimes the process works and the marks can be read. In the case of the Norfolk chest, the writing could be read. The final step is to attempt photography. As we stated in Notes to the Reader in W H Cabinetmaker…, “Successfully photographing ghosts of chalk, ink and pencil signatures and inscriptions on pieces studied is difficult at best, if not impossible….”8 Still this is an important tool to verify what you have seen with your eyes. Even if only some of the letters seen by a personal examination of the furniture are visible in the photograph, a record of those parts of the writing is better that no documentation at all. In the case of the chest, after numerous unsuccessful attempts, two photographs were taken that together, after digital manipulation, illustrate most of the words that could be read in person on the back of the drawer. Written on the drawer is “Josiah C Perdue his work __ the year of our Lord and in 5 of April 1829 in Petersburge in Virginia” (Fig. 6, Portion of writing on Fig. 5) (Fig. 7, Portion of writing on Fig. 5). (As we have done in prior books and articles, an enhancement has been created based on our personal observations of the writing.) Sometimes a photograph will reveal an image on a piece of furniture not previously discovered through personal examination. In this case, the previously discussed process should be reversed, with a personal examination of the site of the photograph to verify the image. Again, even if the whole image cannot be verified, if some of the elements of the writing can be clearly identified this offers some evidence that the image is of something actually on the piece of furniture. Even with the availability of advanced photographic technologies, your eyes and brain are still your most useful tools, if you use them.

An examination of written records and historic documents is another essential step or link to discover the true origins of some pieces of furniture, including the chest signed by Perdue. Why would a Petersburg cabinetmaker create a chest with decorative features found on known Norfolk furniture? Research revealed that Bivins had already discovered several examples of furniture made in Wilmington, North Carolina, with the same Norfolk-based decorative features as seen on the Perdue example. A great deal of trade took place between southern ports in the 18th and early 19th centuries, including Norfolk and Wilmington. Trade was especially heavy between Norfolk and the upriver ports of Petersburg and Richmond. Decorative features and fashion trends flowed with this trade. Historic documents also reveal a strong connection between Norfolk artisans and Petersburg artisans dating back at least to 1776 when John Seldon moved his cabinet shop to the Blandford community next to Petersburg. His Norfolk shop had burned along with the rest of Norfolk. Several examples of Petersburg furniture made with these same Norfolk decorative features can currently be seen in the 1839 Exchange Building in Petersburg. Moreover, this same type of documentary research can illustrate family and geographic ties between artisans and patrons, the migration of both artisans and construction and decorative characteristics from one region to another, and the personal histories of the artisans themselves. This same process is employed by historical archaeologists who use the written record to illustrate and interpret physical fragments recovered during a dig. This type of research is but one of the links that should be considered, along with all the other evidence, when attempting to discover the origin of your favorite antique.

While other methodologies can certainly be applied to the examination of a piece of furniture, it is always essential that all factors or links be evaluated and thoughtfully considered, not just the bits and pieces that fulfill a preconceived idea or make the object what you want it to be. You should never draw a conclusion until all physical and decorative features have been considered and all applicable historical research has been exhausted. You should let the object speak and carry you throughout the process of the investigation. If the search is driven by preconceived ideas or just the desire to revisit your favorite rabbit hole, the true story will be obscured and a false history will be created. Realize that the end of the journey is often inconclusive. However, the journey is still important and should be thoroughly documented. The story may be completed in the future with the discovery of additional information. In a courtroom, after all the testimony and exhibits have been presented and the jury arguments have been made, the judge informs the jury that they should consider all the evidence that has been presented, weigh each piece of evidence using their own good reason and common sense, and from all the evidence find the truth, whatever that truth might be.

By the way, here is the rest of the story of Great Aunt Maude’s favorite mahogany table (Fig. 8, Card table). It is a square mahogany card table of the late 18th century. Its secondary woods are yellow pine, poplar, and river birch. The drawer bottom is beveled and set in dadoes along the drawer front and sides and flush nailed to the drawer back with wrought nails with fairly flat, irregularly shaped heads. No evidence of glue blocks is present under the drawer bottom. The table was purchased from a Richmond estate and has inlay consistent with several other pieces of Richmond furniture, although similar inlay is found elsewhere (Fig. 9, Inlay on Fig. 8). What is your assessment of the table? We are sure Great Aunt Maude will love to hear your ideas during your next visit as you enjoy a second helping of her famous black-eyed peas and corn bread.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figures 6 and 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

Mar 18, 2014 @ 23:22

Endnotes

- John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820, Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988, pp. 155-171.

- Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, Edenton Furniture and Culture, Colonial and Federal Periods, Edenton, NC, Cupola House Association, 2008, pp. 19 and 20, 25 and 26, 28-31.

- Sumpter Priddy, “Musings on a Scottish-Irish Desk Form in Virginia: The Scrutoire”, The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Volume 33, 2012.

- Newbern and Melchor, pp. 17-25.

- Bivins, pp. 495 and 496.

- Patricia A. Piorkowski, Piedmont Virginia Furniture, Product of Provincial Cabinetmakers, Lynchburg, VA, Lynchburg Museum System, 1982, No Pagination.

- Gary A. Albert, The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Volume XXIV, Number 2, Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1998, p. 28.

- Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, W H Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved, Legacy Ink Publications, 2009, p. vii.

Bibliography

Albert, Gary A., 1998, The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts: Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Volume XXIV, Number 2, p. 28.

Bivins, John, Jr., 1988, The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820: Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, pp. 155-171.

Newbern, Thomas R. J. and James R. Melchor, 2008, Edenton Furniture and Culture, Colonial and Federal Periods: Edenton, NC, Cupola House Association, pp. 19, 20, 25, 26, and 28-31.

Newbern, Thomas R.J. and James R. Melchor, 2009, W H Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved: Benton, KY, Legacy Ink Publishing, p. vii.

Piorkowski, Patricia A., 1982, Piedmont Virginia Furniture, Product of Provincial Cabinetmakers: Lynchburg, VA, Lynchburg Museum System, No Pagination.

Priddy, Sumpter, 2012, “Musings on a Scottish-Irish Desk Form in Virginia: The Scrutoire”, The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts: Winston-Salem, NC, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Volume 33.