By Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

Recent scholarship in the study of Southern decorative arts has uncovered a growing number of examples of the business relationship that existed between house joiners and cabinetmakers in the 18th and early 19th centuries. North Carolina’s Roanoke River Basin school of cabinetmaking, as examined in WH Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved, is one such example. Rather than being composed of a number of individual cabinet shops whose masters happened, en mass, to select a secluded section of Bertie County along the Roanoke River near Roxobel to ply their trade, the school actually coalesced around the work product of one craftsman, house joiner William Seay. Artisans were drawn to Seay’s cabinet shop, the physical heart of the school, where they found work constructing houses for the area’s planters and middling farmers, producing trim work for those houses, as well as supplying the furniture to fill their interiors (Fig. 1, Seay cabinet shop). Some workmen stayed a brief time and moved on to work in other areas, while others remained in the Roxobel area for a number of years.

From the earliest years of his career, Seay, like most house joiners of the period, undoubtedly supplied his patrons with cupboards and other simple joined pieces of furniture. His work, however, was of a quality that lead Whitmell Hill, his most prominent patron, to entrust Seay with a large and lucrative furniture commission around 1790, during the time Seay was constructing a new manner house for Hill on his Hill’s Ferry tract. After this commission, Seay engaged in both roles as a house joiner and a cabinetmaker. Seay took a personal interest in his furniture production while continuing to construct houses. While the work of journeymen and apprentices is present, Seay’s furniture shows an obvious and consistent pattern of structure and design supplied by the shop master himself.

A recently discovered hanging corner cupboard is an example of the type of utilitarian furniture supplied by house joiners to their customers in the Roanoke River Basin (Fig. 2, Hanging cupboard) (Fig. 3, Interior of Fig. 2). Constructed of mulberry primary wood and yellow pine secondary wood, this cupboard was purchased a number of years ago from a small house in eastern Northampton County between Rich Square and St. Johns. This places the location of its discovery approximately four miles north east of Seay’s cabinet shop. Mulberry was used in the area for turned furniture elements in the eighteenth century but rarely in case pieces. However, early stands of merchantable mulberry were available and the tree lent its name to Mulberry Grove, the Cotton-family plantation in western Hertford County, approximately two miles to the east of the site of the cupboard’s discovery.

The construction of this rare North Carolina form demonstrates that its maker possessed skills beyond those of a simple carpenter. Rather than using a single large pin to join each corner of the rails and stiles of the cupboard’s door, this craftsman employed finely cut double pins set at 45 degrees for strength (see Fig. 2). Seay used this method of joinery on a number of his case pieces, as did other period cabinetmakers. This maker, however, set the lower right pins at the wrong angle (Fig. 4, Lower right door pins and ghost of lower hinge). A second, even more unusual aspect to the construction of this cupboard is the hinges used to hang the door. The original lower hinge, now replaced, was a small H hinge, probably of iron (see Fig. 4). The original upper hinge was a table-leaf hinge (Fig. 5, Ghost of upper hinge). The use of a table hinge would be unusual if found on a cupboard built of woods intended to be painted along with the hinges, such as yellow pine or poplar. The use of mixed hinges on a cupboard made of primary wood not intended to be painted is even more rare. There is, however, precedent for the unconventional use of a table hinge in Seay’s work. A second-floor door found at the Hermitage in Halifax County, built by Seay for Whitmell Hill’s son, Thomas Blount Hill, is hung by a standard HL hinge at the top and a table hinge of the same size as found on this cupboard at the bottom (see Fig. 68 in WH Cabinetmaker…). Seay’s brother-in-law, Micajah Wilkes, used the same size table hinges to attach the tops of his cellarets to their cases (see Figs. 373, 376, and 382 in WH Cabinetmaker…). Considering this unusual use of a table hinge to hang the cupboard’s door, the quality of its joinery, and the close proximity of the cupboard’s discovery to his cabinet shop, there is a distinct possibility that the cupboard was actually made in Seay’s cabinet shop.

Throughout his career, Seay demonstrated a remarkable degree of consistency in his furniture production and continued to replicate case pieces incorporating many of the same decorative and construction features used in the Whitmell Hill commission. One example is a secretary press currently in the collection of Historic Hope Plantation in Bertie County (see Fig. 2 in WH Cabinetmaker…). Rather than displaying the initials “WH” used on the furniture made for Hill, the initials “CRJ” are found on the tympanum of this piece. The initials commemorate the marriage of Cadwalader Jones and Rebecca Long, which took place on November 6, 1810 in the town of Halifax. This documents 1810 as the construction date for this piece, although it structurally and decoratively matches pieces from the Hill commission.

A small chest of drawers recently discovered in Scotland Neck in Halifax County contains construction features that definitively show it to be Seay’s work and demonstrates that even William Seay bent to the stylistic winds of the area’s closest and most important major port, Norfolk, Virginia (Fig. 6, Chest of drawers). The chest is the first piece of furniture identified from Seay’s cabinet shop that displays more stylish splayed feet set flush with the case sides and front, commonly called “French feet”.

Norfolk served as the major trade center for southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina since the 18th century. By the mid 18th century, Norfolk was dominated by Scottish and Irish factors, merchants, and artisans drawn there by the port’s lucrative tobacco trade. Their presence influenced the furniture produced in areas dominated by Norfolk’s sphere of influence. Differences, however, usually are present which are useful in distinguishing Norfolk production from Norfolk-influenced pieces from other areas. We documented this in detail in Edenton Furniture and Culture…. One example is found on furniture made in Edenton with ball and claw feet displaying a sharp rear talon. A Norfolk example with the same type sharp rear talon was recently published (see Priddy, 2013). However, Norfolk examples are easily distinguished from those made in Edenton by the lack of an indentation where the talon meets the leg just above the ball and claw. In addition to this and other unifying construction details, the Edenton group is further distinguished from Norfolk products by the number of examples with strong provenances and early recovery histories within 20 miles of Edenton. There are numerous known northeastern North Carolina pieces with recognizable Norfolk construction details. We have documented a number of these in WH Cabinetmaker… and in Edenton Furniture and Culture…. Undoubtedly, other northeastern North Carolina and eastern Virginia examples with Norfolk construction details will be found in the future.

The chest in Fig. 6 is composed of walnut with yellow pine and poplar secondary woods. The drawer supports are mortised and tenoned into the drawer blades and back rails. They are not supported in dados cut into the case sides. This is a Seay construction quirk. The drawer blades and back rails are set into open mortises in the front and back of the case sides, in standard Seay fashion (Fig. 7, Drawer support system of Fig. 6) (see Figs. 16, 108, 303, and 318 in WH Cabinetmaker…). The open mortises for the drawer blades on the case front are covered with thick veneer strips of walnut, set in notches cut into the drawer blades. Again, all these construction techniques had been used by Seay as early as the Hill commission of 1790. The case back is composed of horizontal boards set and nailed in rabbetted case sides and flush nailed to the case bottom (Fig. 8, Back of Fig. 6). The case top is supported by horizontal battens dovetailed into the case sides, a standard Norfolk construction technique of the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Fig. 9, Top supports of Fig. 6) (Also note in Fig. 9 drawer support construction details).

The bottom of the case shows both standard Seay construction techniques as well as Norfolk influence (Fig. 10, Bottom of Fig. 6). The double ogee front skirt was standard fair on Norfolk chests from the 1790’s through the 1810’s. Here, rather than being veneered onto a secondary wood, the skirt is solid walnut of the unusually thick stock used by Seay. The front and side skirts are backed by spaced blocks in typical Norfolk fashion. The right front foot, however, is backed by a block reminiscent of Seay’s earlier foot blocking (see Figs. 9, 29, 107, and 308 in WH Cabinetmaker…).

The case drawer bottoms run side-to-side, are beveled, and are set in dadoed drawer sides and fronts. They are flush nailed to the drawer backs. The drawer dovetails are longer and more narrow than those normally used by Seay (Fig. 11, Drawer dovetails of Fig. 6). This seems to be another concession by Seay to Norfolk’s stylistic dominance, although here the dovetails are of equal size and shape at the front and rear of the drawers. In Norfolk work of the period, a drawer’s front dovetails were more narrow and elongated than the rear dovetails. Even with this new influence, Seay continued one of his most consistent traits of drawer construction. Each drawer is marked with the inverted numbers three and four on the back of each drawer back, written in Seay’s hand (Fig. 12, Numbers on drawer back of Fig. 6) (see Figs. 80, 92, 93, 111, 290, and 304 in WH Cabinetmaker…). In addition to the numbered drawer backs, other writing and marks appear on the chest. A series of vertical chalk marks is written on the back of the chest, which cannot be deciphered with certainty. There are also graphite marks on the rear of the second backboard from the top of the case. The marks form SP ciphers written several times horizontally across this board (Fig. 13, SP ciphers on back of Fig. 6) (The upper portion of Fig. 13 shows the actual ciphers as seen in situ. The lower portion of the figure shows the ciphers enhanced for clarity. We have followed this practice in Fig. 20, as well.). These marks probably signify the piece-work of a journeyman with the initials SP. While this person has not been identified, he most likely emulated ciphers used by Micajah Wilkes, Seay’s brother-in-law and co-worker (see Figs. 375 and 389 in WH Cabinetmaker… and Figs. 1, 2, and 4 in Micajah Wilkes… on this website).

In addition to the numbered drawer backs, other writing and marks appear on the chest. A series of vertical chalk marks is written on the back of the chest, which cannot be deciphered with certainty. There are also graphite marks on the rear of the second backboard from the top of the case. The marks form SP ciphers written several times horizontally across this board (Fig. 13, SP ciphers on back of Fig. 6) (The upper portion of Fig. 13 shows the actual ciphers as seen in situ. The lower portion of the figure shows the ciphers enhanced for clarity. We have followed this practice in Fig. 20, as well.). These marks probably signify the piece-work of a journeyman with the initials SP. While this person has not been identified, he most likely emulated ciphers used by Micajah Wilkes, Seay’s brother-in-law and co-worker (see Figs. 375 and 389 in WH Cabinetmaker… and Figs. 1, 2, and 4 in Micajah Wilkes… on this website).

Writing in chalk on the bottom of the chest’s case can be deciphered. It reads “Clark hal” to direct where the chest was to be shipped from Seay’s cabinet shop (Fig. 14, Writing on bottom of Fig. 6). This probably signifies that the chest was made for a member of the Clark family residing in Halifax County. The most likely candidate is David Clark, whose home, Albin, was probably built by Seay in 1808 on the eastern outskirts of present day Scotland Neck. Clark is known to have previously purchased furniture from Seay’s shop, including a demilune table and a cellaret by Wilkes. Considering the style and construction of this chest and the fact it was found in Scotland Neck, 1808 is a likely date for its construction, and it was probably built to help furnish Albin.

A walnut, two drawer blanket chest recently purchased at auction in eastern North Carolina is the second example of this form in walnut known to have been built in Seay’s cabinet shop (Fig. 15, Blanket chest) (see Fig. 192 in WH Cabinetmaker…). Its drawer and case dovetails exactly match those found on the majority of furniture made by Seay (Fig. 16, Drawer dovetails of Fig. 15). Battens are dovetailed to the bottom edge of each end of the top of the blanket chest to prevent warping (Fig. 17, Top batten of Fig. 15). The case feet are each backed by a beveled vertical support, a simplified version of blocking used by Seay on a number of his pieces (Fig. 18, Foot support of Fig. 15) (see Figs. 10, 89, and 308 in WH Cabinetmaker…). The drawer bottoms are beveled along the front and side edges and set in dadoes. The drawer bottoms are flush nailed to the bottom of the drawer backs. The tops of the drawer sides are slightly rounded while the tops of the drawer backs are flat (see Fig. 16). This feature is found on most of Seay’s case pieces, included the previously discussed chest of drawers.

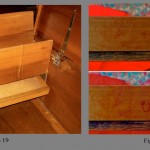

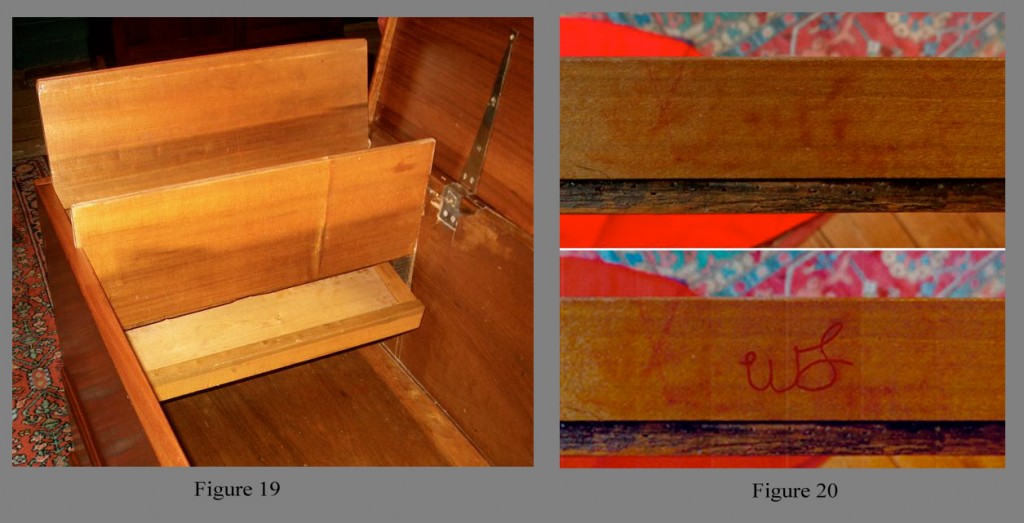

The most unusual and distinctive feature of this blanket chest is found inside the case. The wall of the till slides up to reveal a hidden drawer below the bottom of the till (Fig. 19, Hidden till drawer of Fig. 15). Four examples of yellow pine blanket chests with hidden till drawers are known, three by Seay and one by a member of the Sharrock family. One of the Seay examples displays Seay’s initials on the back of its hidden drawer written by someone other than Seay (see Fig. 199 in WH Cabinetmaker…). An apprentice placed the initials in that location to signify that the work was the property of the shop master and therefore not subject to compensation. The initials WS also are written in the same location on the back of the hidden drawer of this walnut example (Fig. 20, Initials on back of till drawer of Fig. 15). These initials, however, are in Seay’s hand, signifying that the chest was his work product (see Figs. 4, 6, and 75 in WH Cabinetmaker…). It is hard to argue with signed pieces. The furniture and houses of William Seay shed light on the personality of the artisan. Seay served patrons in a rural corner of northeastern North Carolina. He felt a security that allowed him both to explore extravagances of his personality through the decorative elements he chose and at the same time to take liberties in construction, such as the unconventional use of table hinges, only allowed to someone who has risen to the top of the food chain in his respective field. These new discoveries further emphasis these points, but they also show that even Seay bent to the wishes of a clientele exposed to the latest fashion trends that penetrated from Norfolk deep into rural North Carolina’s Roanoke River Basin.

The furniture and houses of William Seay shed light on the personality of the artisan. Seay served patrons in a rural corner of northeastern North Carolina. He felt a security that allowed him both to explore extravagances of his personality through the decorative elements he chose and at the same time to take liberties in construction, such as the unconventional use of table hinges, only allowed to someone who has risen to the top of the food chain in his respective field. These new discoveries further emphasis these points, but they also show that even Seay bent to the wishes of a clientele exposed to the latest fashion trends that penetrated from Norfolk deep into rural North Carolina’s Roanoke River Basin.

The authors especially wish to thank Joe Jenkins for his help in the preparation of this article.

References:

Newbern, Thomas R. J. and Melchor, James R., 2008, Edenton Furniture and Culture Colonial and Federal Periods: Benton, KY, Cupola House Assoc. & Legacy Ink Publishing.

Newbern, Thomas R. J. and Melchor, James R., 2009, WH Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved: Benton, KY, Legacy Ink Publishing.

Melchor, Jim and Newbern, Tom, 2013, Micajah Wilkes, What Is In A Name, A Research Note: Edenton Historical Commission www.ehcnc.org

Priddy, Sumpter, 2013, Musings on a Scottish-Irish Desk Form in Colonial Virginia: The Scrutoire: Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 34.

Published on: May 24, 2013