In an article in the 2013 edition of American Furniture examining the life of cabinetmaker, Thomas Day, the authors described census records of the period as “notoriously prone to error”1 Anyone who has embarked on a detailed study of late 18th and early 19th century North Carolina census records, as well as tax records, stands in solidarity with the authors. The following research note examines certain census and tax records of Bertie County, North Carolina, pertaining to the Sharrock and Seay families. Both families had a number of members engaged as house joiners and cabinetmakers who were away from their respective homes for extended periods as they constructed houses for the wealthy planter families of North Carolina’s Roanoke River Basin. Records that are “notoriously prone to error” in the best of circumstances become especially challenging when dealing with these transient craftsmen.

Taxes levied on people were called poll or capitation taxes, or literally a tax on the head of the individual. North Carolina’s Colonial Assembly first attempted to determine which heads would be subject to taxation in 1715. The criteria for taxation was based on age, race, and gender, but the specifics changed over time. Property taxes, although first levied in 1715, were not a permanent fixture in the generation of government revenue until 1777. The first federal census was taken in 1790, although North Carolina authorized county courts to conduct a population count in 1784. These lists were compiled between 1785 and 1787.2

North Carolina tax and census lists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were organized within the counties by districts. The number of tax districts varied from county to county, and each district list was usually named for the leading militia officer or public official in that particular district. Local officials gathered the necessary data from individuals present on the land. Everything from the number of free whites and slaves subject to taxation, to acreage, to certain personal property, was recorded based on information given by the individual apparently in control of the land. It was therefore to the citizen’s benefit to count heads and acreage low, while public officials obviously benefited from high numbers in both categories.3 It is important to note that the person in apparent control of the land, and therefore supplying information, was not necessarily the legal owner of the property. This point is especially important when considering land owned by individuals who spent a great deal of time away from their property because of their business interests, such as house joiners.

To further compound the danger to the modern historian of a literal interpretation of these records is the repeated use during this period of favored given names within extended family units. As local families grew and expanded in Bertie and surrounding counties, multiple individuals with the same given names and surnames often lived within very close proximity to each other. It was not unusual for relatives with the same names to own adjoining tracts of land. The widespread use of middle names and initials in the public records of Bertie and adjoining counties did not occur until the 1830’s or 1840’s.

One extreme example of this phenomenon is found in Hertford County, located just north of Bertie County. Members of the prominent Sharp family favored the use of the given names Starkey and Hunter. As the Sharp family grew and expanded, there were sometimes three family members named Starkey and three family members named Hunter in a single generation. Sharp family members owned substantial tracts of land in eastern Hertford County on the Chowan River near the present town of Harrellsville, as well as along Wiccacon Creek, a navigable tributary of the Chowan just northwest of Harrellsville. It is easy to imagine the difficulty local officials faced when entering land descriptions of adjoining tracts of land owned by members of this wealthy, extended family sharing the same names.

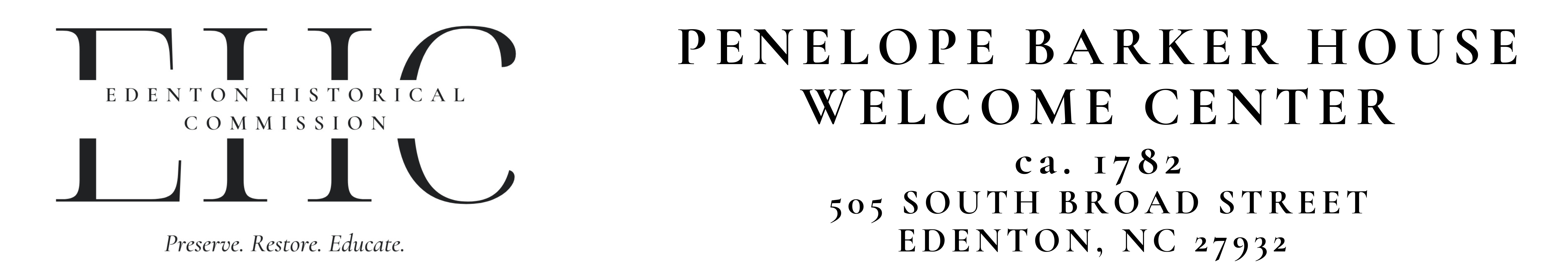

The Sharrock and Seay families of Bertie County did not create problems for local officials on the scale of the Sharps of Hertford County, but their repeated use of favored given names requires that records of this period not be taken simply at face value. No set rules for recording information gleaned from citizens for 18th and early 19th century tax and census records existed. Individual officials devised their own methods for differentiating between individuals with the same name. Some included the person’s father’s name in the listing, such as “John Smith of Thomas”. Many used the suffixes Sr. and Jr., even though in some cases the individuals may not have been father and son. Some officials used Sr. to differentiate the elder, or more prominent, of the two people with the same name, with Jr. signifying the other. An even more unconventional use of these two suffixes is found in the records of the 1812 estate sale of Bertie resident James Hayes.4 The person recording the sale listed Hayes wife as Ruth Hayes, Sr. and another individual as Ruth Hayes, Jr. (Fig.1, Estate of James Hayes). He also spelled the family’s last name as “Hayes” at the top of the page, yet spelled it as “Hays” when referencing the Ruths. A modern researcher might assume that Ruth Hayes, Jr. was the daughter of Ruth Hayes, Sr. The danger is that she actually could have been a niece or other relative of Ruth Hayes, Sr. This is a good example where more research is required. Bertie citizens of the period would have had personal knowledge of these two people, so the use of the suffixes would have served its purpose to distinguish between the two in the written record. You can rest assured, however, when officials of the period created these and other public records, they were not considering the modern genealogist’s ability to understand clearly these records.

The Bertie County tax list of 1803 lists the name Bathsheba Sharrock in Captain Brown’s District, which encompassed the northwestern section of the county, including Roxobel. Beside her name is listed 209 acres.5 This entry, taken alone, would lead the modern researcher to conclude that this woman was the owner of 209 acres of land, perhaps through inheritance or as the result of the death of her spouse. More in-depth research paints quite a different picture. This 209-acre tract was actually purchased by William Sharrock on November 18, 1797 from his brother-in-law, Moses Bishop.6 William was the son of Bathsheba and her husband, Norfolk-trained cabinetmaker, Thomas Sharrock. William died in late 1799. In his will, written on November 17, 1797, just one day before he purchased the land, he left all his property to his son, Griffin. His wife, Winifred, was not mentioned and apparently had died before his will was written.7 In 1803, the land actually was owned by the estate of William or by his son and only heir, Griffin. Bathsheba apparently was the person in control of the land in 1803, although William’s brother-in-law, Moses Bishop, was his executor. Other Bertie County tax lists of the period list the land under its correct ownership. In 1800, the land is listed under the heading “orphan of William Sharrock”.8 In 1802 it is entitled “estate of William Sharrock”.9

Griffin Sharrock was dead by 1805 while still a minor. His uncle and former guardian, Samuel Sharrock, served as his administrator. The 209 acres were dispersed by court settlement to Griffin’s aunt and surviving uncles during the August 1815 term of Bertie County Court.10 The census of 1810, however, again lists this land under the name Bathsheba Sharrock.11 Her name is found listed between the names, Moses Bishop and Jesse Powell, land owners on either side of the 209-acre tract. Bathsheba apparently was in control of the land, just as she had been in 1803. She probably had been in control of the land since her son’s death in 1799 but with no ownership interest. Without this more thorough examination of the available records, however, the true nature of ownership and control of this tract would not be known.

A second example of the uncertainty that can arise from a cursory examination of Bertie County tax and census records involves William Sharrock’s father, Thomas Sharrock. Thomas Sharrock moved to Northampton County, North Carolina in 1762, soon after completing his apprenticeship in Norfolk as a cabinetmaker.12 Shortly after his marriage to Bathsheba Daughtry, he purchased 125 acres on August 11, 1766 in Northampton County adjoining Sandy Run. The deed states the land is to the east side of Sandy Run. This probably was meant to read bounded on the east by Sandy Run, as there is no east side of Sandy Run in Northampton County. Sandy Run is a small stream emitting from a swampy area on the Roanoke River that flows north before turning northeast and east. It forms the western section of the border between Bertie and Northampton Counties. Considering that the deed mentions a reserved area for a mill in a swampy area, as well as “the first branch”, apparently referring to the first stream found on the Northampton County side of Sandy Run after leaving the Roanoke River, this land probably was to the west of Roxobel on the west side of Sandy Run before the stream turns east. Thomas and Bathsheba Sharrock sold this land to William Brown on January 3, 1772.13 Another land purchase know to have been made by members of the Sharrock family took place on January 25, 1790. Thomas and Bryan Sharrock, twin sons of the elder Thomas Sharrock, bought 315 acres from George Nasworthy on the north side of Sandy Run in Northampton County. This land was a portion of a 640-acre tract granted to Robert Sherwood on April 5, 1720.14 Deeds conveying other portions of the Sherwood patent note that Licking Root Branch flows through the land.15 A 1782 grant of 460 acres from the State of North Carolina to Watson Rutland places this stream just northeast of modern day Highway 308 and just north of Sandy Run, thereby locating the twins’ tract approximately one and one-half miles north of the Roxobel crossroads just across the Northampton County line.16

Thomas and Bryan Sharrock were born on December 5, 1767. Thomas died on September 20, 1790, very soon after the purchase of the Nasworthy land. Bryan died on March 1, 1795.17 The 1790 deed states that both Sharrocks were residents of Northampton County, but Northampton County was purposely struck through on the deed.18 Thomas, their father, was appointed administrator of their estates by the Bertie County Court rather than by the Northampton County Court. Their estates were settled in Bertie County, offering evidence that they were both Bertie County residents.19 Thomas and Bryan’s heirs, their brothers and sister, sold the land to Stephen Andrews on March 5, 1796.20

These three Sharrock purchases, William Sharrock’s 209 acres, Thomas Sharrock’s 125 acres, and the twins’ 315 acres, are the only Sharrock land purchases documented by know deeds in Bertie or Northampton Counties from 1766 to 1805. Bertie County tax lists, however, beginning in 1790, list Thomas Sharrock, presumably the father, as a resident of Bertie County with 250 acres of land.21 Of course, the Thomas in the 1790 list could have been the son, Thomas, with his father’s name replacing the son’s name upon the son’s death in September of that year. Again, the records are just not clear. Either way, no deed or will has been found documenting the acquisition of this land by a Sharrock. Thomas Sharrock, the father, continued to be listed in each consecutive Bertie County tax list with 250 acres, as well as two to four slaves, through the tax list of 1800.22 The Bertie County tax list of 1801 also lists Thomas Sharrock, here with three slaves, but does not list any land beside his name.23 The 250 acres is not listed under the names of any of his children nor under the name of his wife, Bathsheba. Thomas Sharrock’s will was written on April 22, 1797, noting that he was a resident of Bertie County, and that he was “very sick of body”. His will makes no mention of the ownership of any land.24 Thomas apparently recovered and was present at David Stone’s Hope Plantation on October 28, 1801, where he and his son, Steven, witnessed the will of Jonathan Bishop. Stone’s house was being constructed at the time, and all three were probably engaged in framing or finish carpentry work.25 Thomas Sharrock died early in 1802. On February 15, 1802, Bathsheba, his wife and administratrix, prepared an inventory of his property. This inventory does not mention the ownership of any land.26 The Bertie County tax list of 1802 lists neither Thomas nor his estate.27 In 1802 and 1803, however, 250 acres of land are listed beside the name of his son, Samuel Sharrock.28 This is the first time Samuel is listed in the Bertie County tax lists. No deed exists documenting a transfer of 250 acres from Thomas or his estate to Samuel. James Sharrock, another of Thomas’ sons, and two of Thomas’ friends, were named by Thomas as executors. All of Thomas’ property was left to Bathsheba for her lifetime. If there had been a transfer of the 250 acres among Thomas’ children, a number of deeds probably would have been required. Thomas’ estate was not settled until 1814. Bathsheba was still administratrix at the estate’s closure.29

The Bertie County tax list of 1805 lists Samuel Sharrock with 1000 acres, land received from a grant from the State of North Carolina, although the grant is dated 1809.30 Samuel listed this same 1000 acres for sale in the Edenton Gazette on November 18, 1817.31 No deed has been located documenting the sale by Samuel of the 250 acres listed beside his name in 1802 and 1803.

A researcher finding 250 acres listed beside the name, Thomas Sharrock, in the Bertie County tax lists probably would assume that he was the owner of the land. Evidence uncovered by a more complete examination of the available records argues otherwise. Bertie County and Northampton County deed books appear to be intact. Yet no deed for the purchase or sale of the 250 acres by Thomas Sharrock or by Samuel Sharrock can be found. The question becomes why was the land listed beside their names? Perhaps they were living on and in control of a friend’s or a relative’s land. Perhaps they leased the land. Bertie County estate records are replete with references of the rent of the land of orphans to non-relatives. Some tax listings reference the ownership of land by orphans, but not nearly as often as references are found in estate records. Those other times, the person renting and in charge of the land must have been listed in the tax records.

The 250 acres listed beside Thomas Sharrock’s name seems to be another example where a cursory examination of some of the available records could lead to an incorrect interpretation. The listing does, however, offer evidence of the date by which Thomas Sharrock was residing in Bertie County rather than Northampton County, most likely with other members of his family. During Bertie County’s August Court of 1792, “Thomas Sherlock and his hands”, along with William Andrews, Amos Harrell, and Noah Hollowell, were ordered to work on a new piece of road “from the mouth of Mill Gut to the mill”. At the same time, Reuben Norfleet was appointed overseer of this new road. During the same term of court, Sharrock also was appointed, along with Jesse Brown, Henry Rhodes, and Josiah Granberry, to divide the lands of Richard Williams, deceased.32 All of these individuals resided to the south and west of the Roxobel crossroads between the crossroads and the Roanoke River. The mill in question was later known as Bishop’s Mill. It was located southwest of Roxobel near the original location of Sandy Run Baptist Church, then know as Bertie Church. These references give a good indication where the 250 acres credited to Thomas Sharrock was located. Although Sharrock had worked for and with William Seay before 1790, these tax listings are evidence of his relocation from Northampton County to Bertie County and the Roxobel area at least by 1790 to take further advantage of the growing house joining enterprise of William Seay.

A third example of the danger of a literal reading of tax and census records involves records as they pertain to William Seay, or more accurately, to the William Seays. There are four know William Seays who lived in Hertford and Bertie Counties during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One William Seay is found in the Hertford County census of 1790.33 The 1790 Hertford County census listings seem to have been created as the census takers traveled from farm to farm as they gathered information. The individuals listed just before this William Seay all lived along the Chowan River in eastern Hertford County. Most of the other known Seays lived in the section of Bertie County bordering the southwest section of Hertford County, or the opposite end of the county. Some of the names appearing on the Hertford County census list just before William Seay’s name include Jemima Sharp, the widow of Starkey Sharp, who lived near the present community of Harrellsville near the Chowan River. Elisha Scull lived just northwest of the Sharps near Wiccacon Creek, a tributary of the Chowan River. Cornelius and William Evans lived in the same area. The two names that appear directly above William Seay are Samuel and Noah Cotton, the sons of Thomas Cotton and Patience Bridgers. These members of the extended Cotton family appear to have lived near Winton on the Chowan River northwest of Harrellsville.34 The names on the 1790 census appearing after William Seay’s name were individuals who lived near the Chowan River northwest of Winton towards Murfreesboro, a town located upriver from Winton. This is probably the same William Seay who appears in the 1800 census of Hertford County.35

At the same time the first William Seay was residing in Hertford County, a second William Seay lived in northwestern Bertie County near the Roxobel crossroads. This individual was the wealthy house joiner and cabinetmaker. On February 1, 1790, the same year Hertford County’s William Seay was counted for the Hertford County census, the second William Seay, identifying himself as a house joiner of Bertie County, sold 20 acres of land to John Acree adjoining land Seay had inherited from his father, Dr James Seay.36

A third William Seay was the son of Issac Seay, who was the son of Dr. James Seay and the brother of house joiner William Seay. After the death of his father, Isaac, this William was apprenticed to Marmaduke Norfleet in August 1790 to learn the trade of a shoemaker. William married Caroline Murray on January 6, 1803 and died in 1808.37 The fourth William Seay was the son of house joiner William Seay. He is found listed in the records of John D. White’s Roxobel store in 1802, but he is not listed after 1802.38

A casual examination of the records pertaining to Bertie County’s three William Seays can lead to mistakes and omissions. Issac Seay died late in 1788 or early in 1789. An inventory of his property was taken on February 14, 1789, and listed 300 acres of land.39 The Bertie County tax list of 1799 shows the orphans of Isaac Seay with 233 acres.40 This is an example of the intentional or accidental diminution of acreage for tax purposes. When Isaac’s land finally was divided between his two sons, William and Robert, on October 15, 1808, each received 153 acres, for a total of 306 acres. William had died just prior to May 9, 1808, so his share of his father’s land went to his estate.41 The 306 acres almost exactly matches the 300 acres of land listed in Isaac’s inventory and shows that no land had been sold from Isaac’s estate between 1789 and 1799, when the tax list shows 233 acres. In 1800 and 1801, the tax lists show 228 acres for the orphans of Isaac Seay, a slight variance from the diminished 233-acre amount.42 After 1802, there are no listings for the orphans of Isaac Seay in the Bertie County tax lists. In 1802, Isaac’s oldest son, William, had come of age, and the same 228 acres is listed under his name. He was listed as William Seay, Jr. to differentiate him from another William Seay listed in that year‘s tax list as senior.43 In 1803, the second William Seay had died, and Isaac’s land continued to be listed under his eldest son’s name, now simply William Seay.44 The listing continued under the name William Seay as 233 acres through 1807, although the 1807 listing of 333 acres is undoubtedly a recording error.45 As stated previously, Isaac’s land was divided in 1808 between his two sons, William, then deceased, and Robert. The tax list for 1808 notes the division of the diminished amount of 233 acres. Both William’s heirs and Robert are listed in the 1808 Bertie County tax list with 116 ½ acres, totaling the diminished tax listing of 233 acres.46

The formal division of Isaac Seay’s land in 1808 apparently tipped off the taxman. The 1809 tax list records 153 acres besides the listing “Wm Seay by Wm Acree”, the correct amount of acreage William’s estate had actually received on October 15, 1808.47 The listing of William Acree adds an interesting point to the interpretation of Bertie County tax lists. The sale of the estate of William Seay, the son of Isaac, took place on December 22, 1808. At the end of the sale, the notation “The land leased for 3 years payable yearly 1/3” is written beside the name William Acree.48 This signifies that Acree was leasing the land from this estate. It appears that this was not the first time Acree leased this land. Bertie County tax lists for the years 1796 through 1798 do not have a listing for Isaac Seay’s orphans, or any comparable listing, for the 233 acres found in the 1799 tax list. William Acree, however, is listed from 1796 through 1798 with this same acreage, 233 acres.49 Tax lists that are available for the years immediately preceding 1796 list William Acree with no land.50 Tax lists from 1799 through 1807 again list William Acree with no land.51 This offers strong evidence that William Acree leased the 233 acres listed in 1799 under the heading orphans of Isaac Seay for the years 1796 through 1798, and that the Bertie County tax lists for those three years listed the land under the name of the lessee rather than under the name of the owner. Equally important to the examination of the dangers of a literal reading of these tax lists is the point that William Seay, Jr., as listed in the 1802 tax list, was in fact William Seay, the son of Isaac Seay. This is an example of an official of the period using the suffix Jr. to differentiate between two individuals of the same name who were not father and son. So if the William Seay, Jr. of 1802 was not actually William Seay, Jr., but was William Seay, son of Isaac Seay and nephew of house joiner and cabinetmaker William Seay, then who was the William Seay, Sr. listed in the 1802 tax list and whose death was recorded in the 1803 tax list?

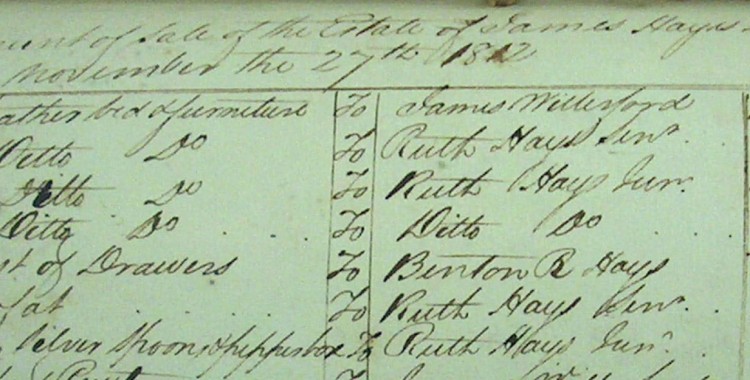

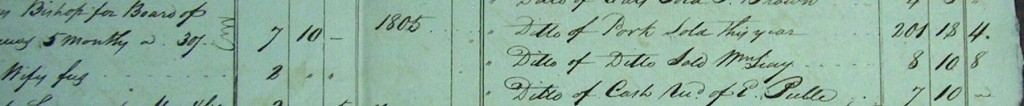

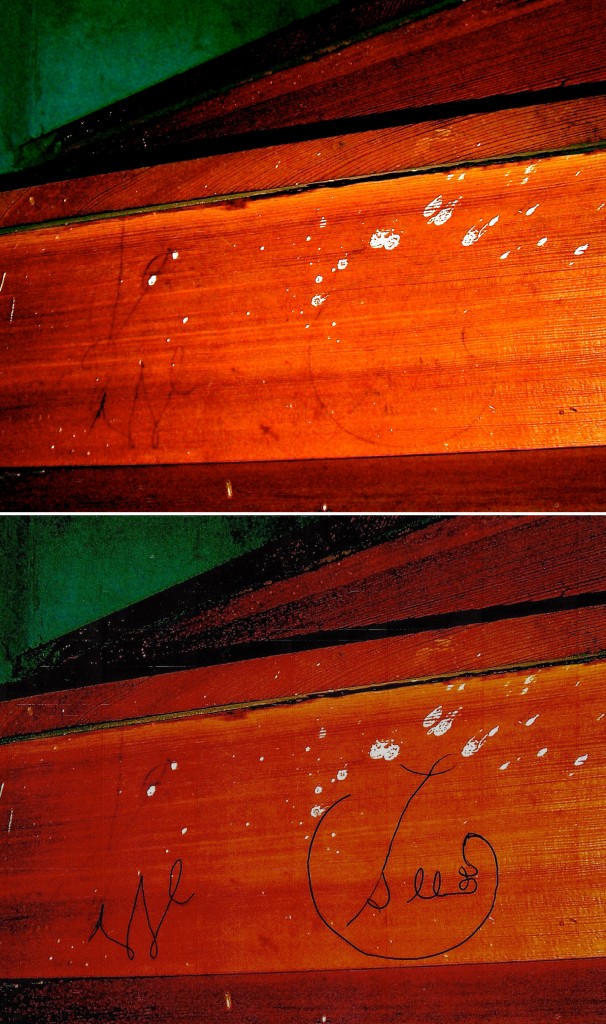

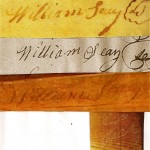

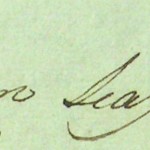

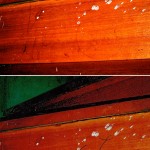

The William Seay whose death is documented in the 1803 Bertie County tax list is noted in the 1802 tax list to have been the court appointed guardian of Peggy Andrews, the daughter of prominent local planter, Stephen Andrews.52 Documents found in the Stephen Andrew’s estate hold the answer to the identity of this William Seay. Several examples of the signature of William Seay, the house joiner and cabinetmaker, survive. His signature remained remarkable consistent over a thirty-five year period (Fig. 2, Signatures of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker). The earliest examples are found on two apprentice bonds dated May 11, 1774. On that date, Seay took Joel Bird as an apprentice carpenter and house joiner and Charles Rhodes as an apprentice carpenter.53 Seay’s signature on the Bird indenture is illustrated at the top of Fig. 2. His signature on the Rhodes indenture is identical except it appears the ink forming the top of the “S” in Seay either faded out or was not emitted from the quill. The next example appears on an administrative bond dated August 18, 1789, and is shown as the second signature in Fig. 2. Seay served as one of two bondsmen for Noah Hollowell as Hollowell qualified as administrator of the estate of his deceased brother, Cadar Hollowell.54 The third signature in Fig. 2 appears on the upper interior edge of a drawer side in the secretary press Seay built for Perry Tyler around the time of Tyler’s marriage in 1792 (See WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 3 and 4, and “Original Owners of Historic Hope Foundation’s China Press” at www.ehcnc.org/decorative-arts/furniture). The last known signature of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, illustrated at the bottom of Fig. 2, appears on the interior rear panel of a built-in press in the Pugh-Griffin house, constructed around 1811 or 1812 in Woodville in Bertie County (See WH Cabinetmaker…, Fig. 291). The enhancement of this signature was created based on the authors’ personal observations of the signature in situ. As we stated in “Notes to the Reader” in WH Cabinetmaker…, “Successfully photographing ghosts of chalk, ink, and pencil signatures and inscriptions on pieces studied is difficult at best, if not impossible…. Below the photographs of the actual signatures and inscriptions, enhanced views, created from personal examinations of the pieces, have been included.”55 The signature seen at the bottom of Fig. 2 is the enhancement portion of Fig. 291 in WH Cabinetmaker… and was created from what plainly could be seen using different lighting techniques in the rear of the Pugh-Griffin built-in cupboard. Ironically, when the photograph of the Pugh-Griffin signature with the accompanying enhancement was compared to other know signatures of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, it was found to be totally consistent with other know examples of his signature.

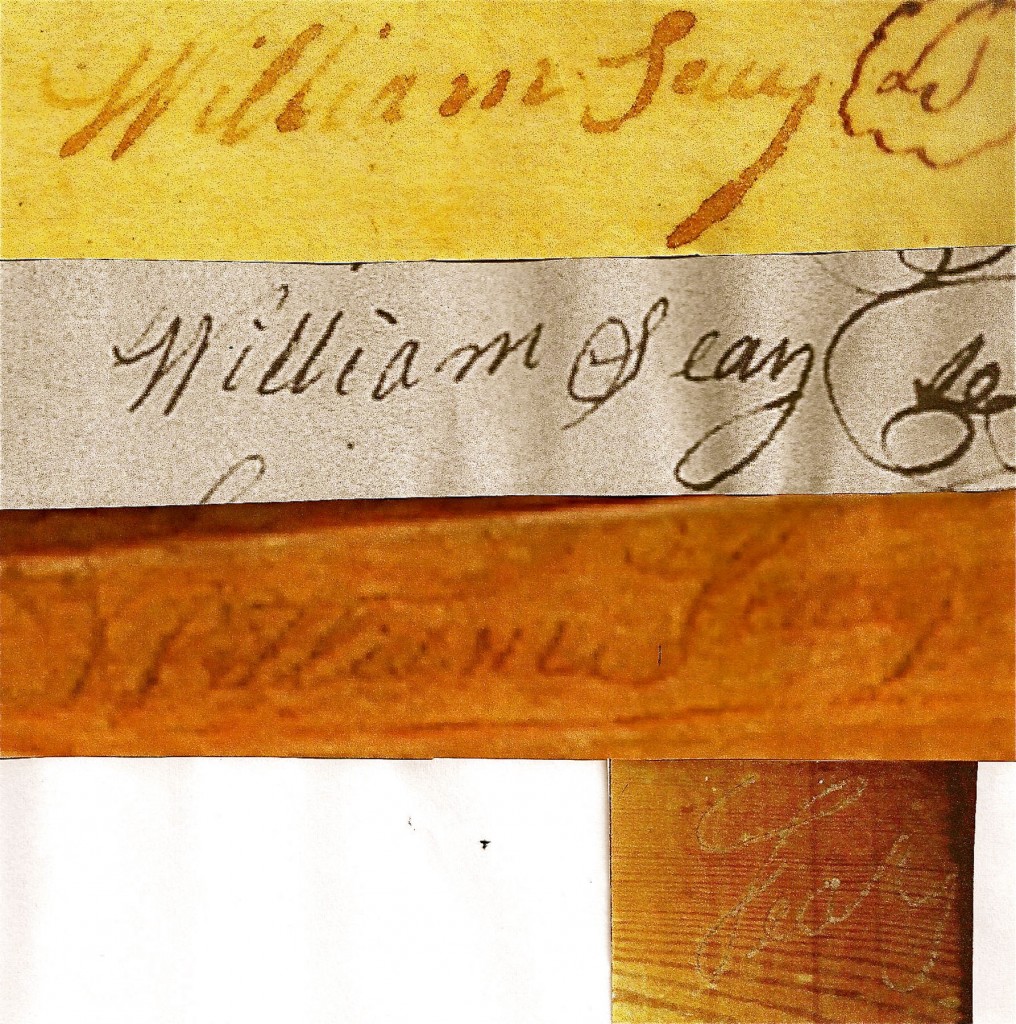

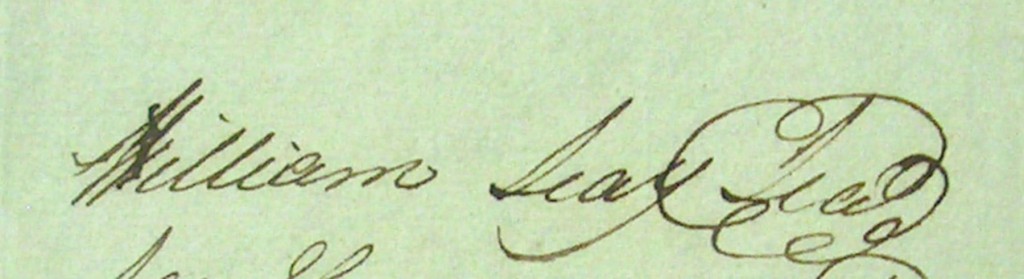

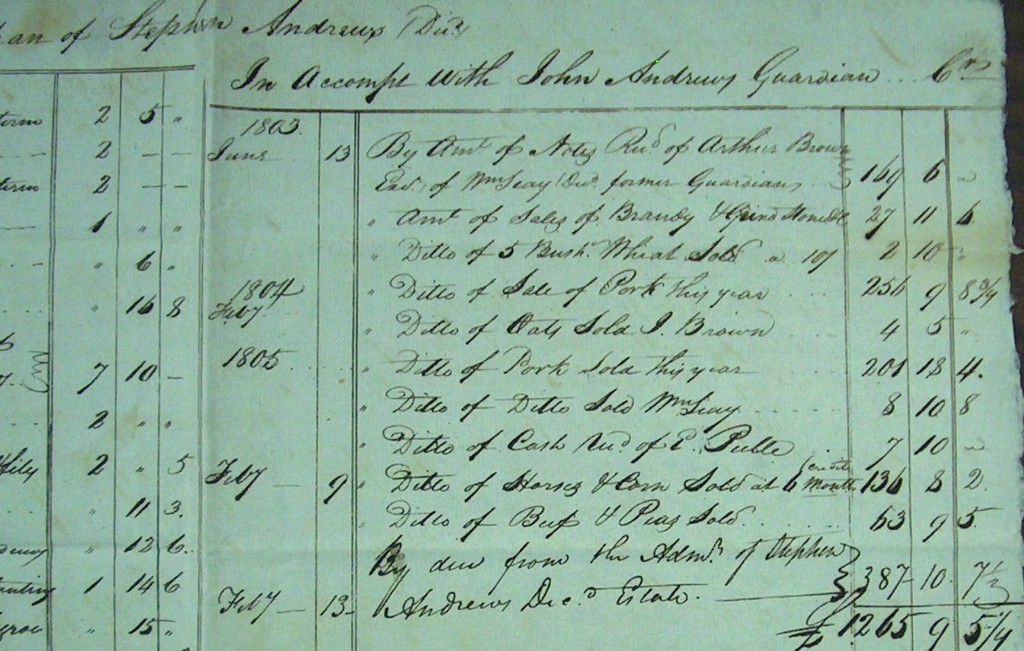

Fortunately, the signature of the William Seay who died in 1803 is preserved in the Stephen Andrews estate papers (Fig. 3, Signature of William Seay who died in 1803). This William Seay signed the guardianship bond when he became the guardian of Peggy Andrews on May 12, 1800. Also found a few pages later in this same Stephen Andrews estate file is a balance sheet entitled “Peggy W. Andrews Orphan of Stephen Andrews Dec’d”. On the side of the sheet listing debts owed to the estate for the year 1805 is listed eight pounds, ten shillings, and eight pence owed to the Andrews estate for the sale of pork by the estate to “Wm Seay” (Fig. 4, Excerpt from Stephen Andrews estate) (Fig. 4a, Close-up of Fig. 4).56 Assuming that dead men do not buy pork, even in northeastern North Carolina, the fact that William Seay was listed in the estate as buying pork in 1805 after William Seay was listed in the same estate as having died in 1803, should serve as a clue to any researcher that there were at least two William Seays and more research needs to be done.

Two factors are important when comparing handwriting. The first, and most obvious, is to compare formation of the individual letters. The “W” in William in the first three examples in Fig. 2 begins and ends with a sweeping flourish, and the lowest points of each “W” are created with small reverse loops. 1803-William Seay’s “W” does not show either feature. It should be noted that these same unusual reverse loops are also present on the “W’ in the name “W Seay” found written inverted on the back of a stair riser in the rear-stair cubby hole at Hope Plantation, built by Seay in 1803 for Governor David Stone (Fig. 5, W Seay written on stair riser at Hope). (The enhancement in Fig. 5 is based on the personal observations of the writing by the authors.) Although this signature is not in Seay’s hand, a likely explanation for the similarity of the “W” found at Hope to the handwriting of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, is found in the wording of the apprentice bonds of 1774. Seay was required to teach each apprentice “to read and write before the expiration of his apprenticeship…”.57 The same unusual handwriting feature being present in both instances may be the result of that requirement.

A further comparison of the four illustrated signatures of house joiner and cabinetmaker, William Seay, to the one known signature of 1803-William Seay demonstrates how distinct and dissimilar they are. The “m” at the end of “William” in the signature of 1803-William Seay curves back on itself. This feature is not found in the three Seay signatures illustrated in Fig. 2 containing his first name. The “S” in Seay in the four signatures in Fig. 2 is similar to a capital “L”, with the bottom loop turning back on itself and sometimes crossing. The “S” in Seay in the signature of 1803-William Seay is formed as a small case letter with an exaggerated point. The “y” in each of the four signatures in Fig. 2 turns back on itself, sometimes crossing. The “y” in the signature of 1803-William Seay carries back all the way to the first letter in the word, where it terminated under the “S”.

The second important consideration in examining handwriting is how the words themselves are formed. In this case, the slope of the signature of 1803-William Seay is much more exaggerated that the four know signatures of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker. Even more importantly, the way an individual joins letters as he writes, especially the first letter in a word to the next letter in the word, is very telling. 1803-William Seay continued his writing stroke from the “S” in Seay to the “e” in Seay without lifting his hand. William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, consistently created the “S” in Seay, lifted his hand, and then wrote the rest of the word.

All of these points of distinction between the signature of 1803-William Seay and the four illustrated signatures of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, clearly show that they were written by two different people. William Seay Jr. of the Bertie County tax list of 1802 turns out to be William Seay, son of Issac and nephew of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker. William Seay Sr. of the Bertie County tax list of 1802 is clearly not William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker.

With William Seay, Jr. of the tax list of 1802 now shown to be William Seay, the son of Isaac, and William Seay, Sr. of the tax list of 1802 now shown not to be William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, the only William Seay left in Bertie to have been the William Seay, Sr. of the tax list of 1802 is William Seay, the son of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker. The name of the individual listed in 1802 as William Seay Sr. was recorded beside the land taken to be the plantation inherited and acquired by William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, and he was the person appointed as guardian for Peggy Andrews. It is logical that the adult Seay family member who was in charge of running the plantation, rather than the adult family member who was often absent from the plantation and often traveling from work site to work site as a house joiner, would be the choice to serve as guardian for a close neighbor’s orphaned child. Based on estate records pertaining to the Sharrock family, William Sharrock appears to have been the family member in the role of plantation manager, while his father and his brothers engaged in the cabinetmaking and house joining trades. As previously stated, William Seay Jr. is found listed in the receipt book of Roxobel merchant John D. White in 1802, but then is no longer found. This absence is explained by his death, as noted in the 1803 Bertie County tax list. His death occurred before May 10, 1803, when John Andrews was appointed guardian of Peggy Andrews in his stead.58 Merchants probably were more definitive in their record keeping when issuing credit than were tax collectors who really did not care who paid taxes due, just so someone did. At some point, the William Seay listed in the tax lists came to represent the son rather than the father. After 1803, the house joiner and cabinetmaker’s son-in-law, Lemuel Murdaugh, was listed with the property. On March 16, 1801, however, Murdaugh witnessed a deed in Halifax County from John Bell, Sr. to John Drew for land adjacent to Marmaduke Norfleet.59 All three of these named individuals were members of families know to be clients of William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker. The Halifax tax list of 1802 shows Murdaugh in Halifax County with no listed property. He was located in District 7 near Drew Smith, a nephew of Captain James Smith, the owner of a Seay-built cellaret (See WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 129-132).60 The 1802-District 7 tax list was compiled by John Anthony. Anthony was the son-in-law of Whitmell Hill, who hired Seay in 1790 for Seay’s largest furniture and house building commission. Based on the age of Lemuel and Elizabeth Seay Murdaugh’s children when they inherited the Seay plantation in 1818, Lemuel was married and had children during his stay in Halifax County in 1801 and 1802. In all likelihood, Murdaugh was engaged in a building project for Seay in Halifax County during this period. After May 1803, however, he returned to Bertie County and apparently moved into the vacated role of plantation manager.

William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker, continued his trade until his death around 1811 or 1812, after he signed his name in the Pugh-Griffin house. On May 25, 1808, he issued a note to his nephew Robert Seay, the son of his brother Isaac. Robert had died before May 1810. This note is listed on a balance sheet in the estate of Robert Seay as “By balance due on Wm Seay’s note 25 May 1808”.61 The William Seay now understood actually to be Willam Seay Jr., the son of the house joiner and cabinetmaker, had died in 1803. The only other William Seay in the area of Roxobel, William Seay, the son of Isaac Seay and brother of Robert, had died a little over two weeks before this note was issued, with Arthur Brown being appointed administrator for his estate on May 9, 1808.62 Assuming dead men do not issue notes, the only William Seay who remained alive on May 25, 1808 was William Seay, house joiner and cabinetmaker. Deeds concerning land bordering the west side of the house joiner and cabinetmaker’s plantation would have proved problematic for officials of the day. William Seay, the son of Isaac, inherited the portion of his father’s plantation that adjoined the lands of Isaac’s brother William Seay, the house joiner and cabinetmaker. Deeds to lands bordering the east side of the house joiner and cabinetmaker’s lands did not pose this difficulty. One deed, dated May 10, 1805, details the sale of 68 acres from Lewis Cotton, executor of the estate of his father, Jesse Cotton, whose plantation lay to the east of Seay’s plantation, to Peterson Brown, a Roxobel-area merchant and landowner. The description of its boundaries includes several references to William Seay’s lines and corners, evidencing Seay’s ownership of the land despite the fact that the tax list for that year records his plantation in the name of his son-in-law, Lemuel Murdaugh.63 On November 8, 1806, Brown sold this same tract to Lemuel Murdaugh.64 Between 1805 and 1806, William Seay apparently had given a portion of his holdings bordering the Brown tract to his daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Lemuel Murdaugh. The 1806 deed references one section of William Seay’s line as being “now Lemuel Murdaugh’s line”. The other boundaries, however, are distinguished from this section and specifically stated to be William Seay’s corners and lines, again evidencing Seay’s continued ownership of his plantation. Lemuel Murdaugh was struck by lightning in his home and killed on May 20, 1812. Elizabeth, his wife and William Seay’s only living heir, had died only 10 days earlier.65 Seay’s plantation passed to Lemuel and Elizabeth’s children and heirs through Elizabeth’s estate, not Lemuel’s.66 This is important in two respects. First, it shows that William Seay must have predeceased Elizabeth in death, although probably not by much time considering his work on the Pugh-Griffin house as evidenced by his signature on the back wall of the built-in press. If Elizabeth had died before her father, his property would have passed directly to her children rather than to them through her estate. Second, it shows that despite his name being listed on the Bertie tax records with this land from 1804 until his death, Murdaugh did not own the land. It was owned by Seay until it passed to Elizabeth, probably shortly before her death. Murdaugh’s estate does reflect that he owned some amount of land in his own name, although the amount is not specified. This was probably the land purchased from Peterson Brown. No other known land purchases by Murdaugh are recorded in Bertie County records. Murdaugh was managing the Seay plantation after 1803. His personal estate, however, shows he retained the vestiges of earlier times when he worked with and for William Seay. His personal estate included a carpenter’s adz, approximately twenty chisels, several gouges and drawing knives, hand saws, a cross cut saw, a lot of tools, a “cutting box” and planes, a parcel of shingles, brick molds, and a work bench. No lumber was listed, so he had apparently retired from the trade, probably after 1803.67

William Seay likely began his career as a house joiner shortly before the death of his father, Dr. James Seay. Dr. Seay died in late 1773 or early 1774. The sale of “Part of the Estate of the Late Dr. James Seay” took place on January 20, 1774. While the items sold evidence his profession, as well as his wealth, including three “Doctor books”, a dictionary, vials of medicine, surgeon’s tools, money scales, and a pair of gold buttons, they also bear witness to his probable earlier training as a woodworker. These items included three planes and stocks, augers, one cross cut saw rest, files, a “parcel of carpenter’s tools’, and a small quantity of bedstead timbers. His sons William and Isaac were adults at the time of the sale, while his sons John and James were minors. William, the eldest, had received his share of his father’s land before his father’s death and probably was already engaged in continuing the house joining aspect of the family business. His only purchase at his father’s estate sale was one of the most expense items, his father’s silver watch, valued at four pounds six shillings. Isaac, on the other hand, made a number of purchases, including perhaps the most unique item, his father’s “Tame deer & bell”.68

William Seay and his three brothers each inherited around 250 acres from their father. According to the tax listings, the amount of land owned by Isaac, and later his estate, and James remained about the same through the first decade of the nineteenth century. John sold his 230-acre share of his father’s estate to Amos Harrell in 1792.69 William is listed as owning 250 acres and two slaves in 1783.70 By 1790, his land holdings had increased to 680 acre, while still owning two slaves.71 His increase in wealth undoubtedly was due to his activities as the most prominent house joiner in the Roanoke River Basin. His wealth increased dramatically from 1790 to 1791, ironically the same time he received the Whitmell Hill furniture commission. In only one year, his land holdings grew by 145 acres and his slave holdings grew from two to eight slaves.72 This represents a very large increase in wealth over a very short period of time. Although Thomas Sharrock and his sons undoubtedly worked for and with William Seay before 1790, 1790 was also the year Thomas Sharrock was first listed in Bertie County tax records in control of land very near William Seay. Seay undoubtedly constructed cupboards and other utilitarian pieces before 1790 in conjunction with his house joining enterprise. He also probably had completed some case pieces utilizing his method of supporting case drawers based on mortise and tenon framing so prevalent in house construction of the period. After the Hill commission, however, the furniture making aspect of Seay’s business really began in earnest. From 1790 until his death in 1811 or 1812, in addition to constructing and overseeing the construction of numerous homes for the Roanoke River Basin’s planter elite, he maintained his cabinet shop where he built desks, chests of drawers, elaborate corner cupboards, some with Masonic decorative elements, and other case pieces. While elements of his unique construction techniques, based on his training as a house joiner, are found on pieces constructed by his former apprentices and journeymen as they ventured west into counties such as Halifax, Warren, and Franklin, there is no evidence that anyone incorporated all of Seay’s construction techniques in their furniture. The latest piece of furniture that can be attributed to Seay’s hand is a French-foot chest exhibiting his unique combination of square, horizontal, foot blocking, mortise and tenon drawer support framing, and unique drawer numbering system (Fig. 6, Seay chest of drawers). “Clark Hal” is written under the case, probably signifying its construction for David Clark during the construction of Clark’s home, Albin, in 1808 in Halifax County. The last house that can be attributed to Seay is the Pugh-Griffin house in Woodville in Bertie County, which was constructed around 1811 or 1812, and possibly completed after his death.

In addition to his written signature on the backboard of the built-in press in the Pugh-Griffin house, a construction signature of William Seay is also present on the front of this press. Most late 18th and early 19th century cabinetmakers, who used rosette-and-bail pulls on their chests of drawers and presses, placed the rosettes of the pulls nearly aligned with the horizontal centerline of each drawer front. This resulted in the lower portion of the bail hanging below the horizontal centerline. Seay, however, consistently set the rosettes of his pulls noticeably above the horizontal centerline of each drawer front on his chests of drawers and presses (Fig. 7, Pulls on William Seay chest). Although some other craftsmen certainly set their rosettes in a manner similar to Seay, most Roanoke River Basin craftsmen set their rosettes very near the horizontal centerline of their drawer fronts. Based on available examples of their work, the Sharrocks and Micajah Wilkes followed this norm. Conversely, the bail placement on the signed, built-in press in the Pugh-Griffin house follows the strong William Seay construction trait of rosette placement noticeably above the horizontal centerline of its drawer fronts (Fig. 8, Pulls on built-in press in Pugh-Griffin house). This trait, the unique Seay drawer construction numbering system on the backs of the press’ drawers, and his name written in the back of the press in a handwriting completely consistent with Seay’s know handwriting (See WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 189-192), all offer a compelling case for his personal involvement in the construction of the built-in press in the house he built for William Alston Pugh.

The tax and census records of Bertie County and elsewhere are a mixed blessing. They contain a wealth of information not available elsewhere that offers the modern historian or researcher a glimpse into a world shrouded by the passage of time. It must be remembered, however, that they were not written with the modern researcher in mind. They were created by individuals intent on bringing order to the records of land ownership and possession in a time of political and social upheaval. They contain understandable inconsistencies created by the competing interests of the individuals involved in their creation and by a lack of uniformity in methods employed to record gathered information. Herein lies the danger. Whether the modern researcher simply relies on a convenient single bit of recorded information or is in search of that reference which will justify a preconceived idea, the end result is likely to be misinformation. This research note has highlighted but a few examples found in Bertie County tax and census records whose meanings seem understandable when examined alone, but tell a different and much fuller story when read in the context of other available records.

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 4a are published courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Fiigure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 4a

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

ENDNOTES

- Patricia Dane Rogers and Laurel Crone Sneed, “The Missing Chapter in the Life of Thomas Day”, American Furniture, (2013) p. 124.

- Helen F.M. Leary and Maurice R. Stirewalt, North Carolina Research Genealogy and Local History, “Tax and Fiscal Records” by Raymond A. Winslow, Jr., The North Carolina Genealogical Society, Raleigh, NC, 1980, pp. 214-222.

- Ibid, p. 216.

- State Archives, Bertie County, Record of Estates, Vol. 15, p. 409.

- State Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1803.

- Bertie County Deed Book S, p. 54.

- Bertie County Will Book E, pp. 77-78.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1800.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1802.

- State Archives, Estate Records, Griffin Sharrock Estate.

- Bertie County Census of 1810.

- Thomas R.J. Newbern and James R. Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker, A Southern Mystery Solved, Legacy Ink Publishing, 2009, pp. 143-144.

- Northampton County Deed Book 4, p. 40 and Book 5, p. 180.

- Northampton County Deed Book 8, p. 243.

- Bertie County Deed Book C, p. 103.

- Northampton County Deed Book 7, p. 193.

- John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, NC, 1988, pp. 501 and 503.

- Northampton County Deed Book 8, p. 243.

- Archives, Estate, Thomas and Bryan Sharrock Estate.

- Northampton County Deed Book 10, p. 226 and Book 11, p. 48.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1790.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1790-1800.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1801.

- Bertie County Will Book E, pp. 127-128.

- Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, p. 173.

- Archives, Estate, Thomas Sharrock Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1802.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1802-1803.

- Archives, Estate, Thomas Sharrock Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1805.

- Raymond Parker Fouts, Abstracts From the Edenton Gazette and North Carolina General Advertiser, 1813, 1814, 1816-1819 Volume III, GenRec Books, Cocoa, FL, 1993, pp. 55-56.

- Weynette Parks Haun, Bertie County North Carolina Court Minutes, 1788-1792, Book VI, Self Published, Durham, NC, 1984, Entries 946 and 950.

- Hertford County Census of 1790.

- Sally’s Family Place, Entries Starkey Sharp, Captain Elisha Scull, Peter Evans, and Thomas Cotton.

- Bertie County Census of 1800.

- Bertie County Deed Book P, p. 47.

- Haun, Bertie County, p. 67, Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, p. 246, and Archives, Estates, William Seay Estate.

- Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, p. 119.

- Archives, Estates, Isaac Seay Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1799.

- Archives, Estates, Isaac Seay Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1800-1801.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1802.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1803.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1804-1807.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1808.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1809.

- Archives, Estates, William Seay Estate.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1796-1798.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1788-1790, 1792-1794.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1799-1807.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1803.

- State Archives, Apprentice Bonds and Records, 1774.

- Archives, Estates, Cadar Hollowell Estate.

- Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, p. vii.

- Archives, Estates, Stephen Andrews Estate.

- Archives, Apprentice, 1774.

- Archives, Estates, Stephen Andrews Estate.

- Halifax County Deed Book 19, p. 131.

- Archives, Halifax County Tax List, 1802 and Newbern and Melchor, WH Cabinetmaker…, pp. 130-131 and 206.

- Archives, Estates, Robert Seay Estate.

- Archives, Estates, William Seay Estate.

- Bertie County Deed Book T, p. 464.

- Bertie County Deed Book T, p. 471.

- Raymond Parker Fout, Abstracts From the Edenton Gazette and North Carolina General Advertiser, 1810-1812, Volume II, GenRec Books, Cocoa, FL, 1991, p. 139.

- Bertie County Deed Book Y, p. 61.

- Archives, Estates, Lemuel Murdaugh Estate.

- Archives, Estates, James Seay Estate.

- Bertie County Deed Book P, p. 306.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1783.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1790.

- Archives, Bertie County Tax List, 1791.