By Tom Newbern and Jim Melchor

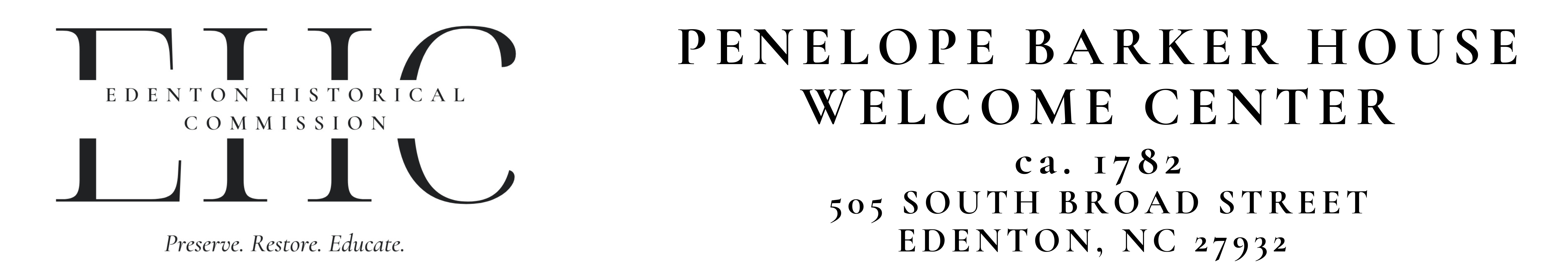

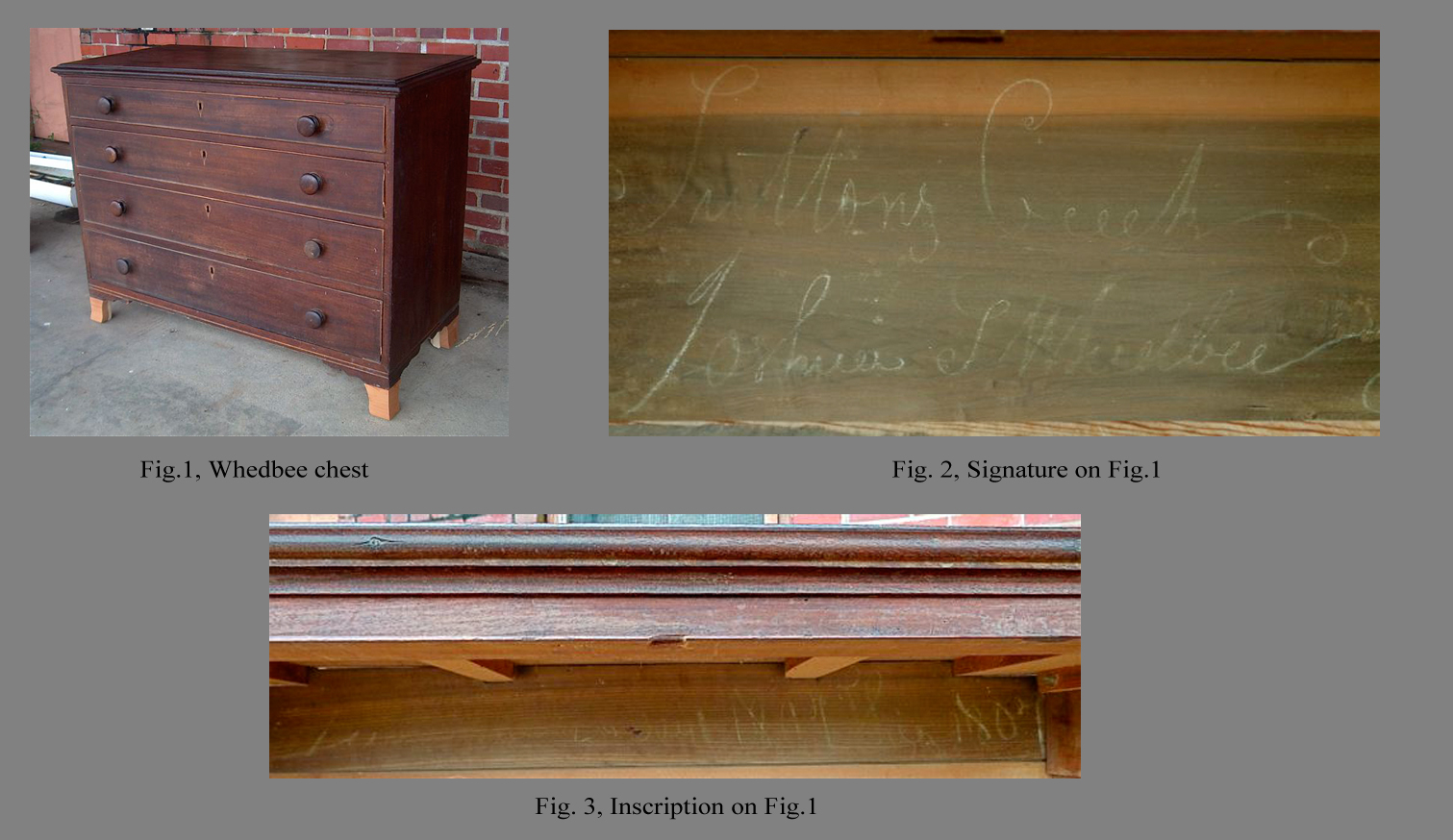

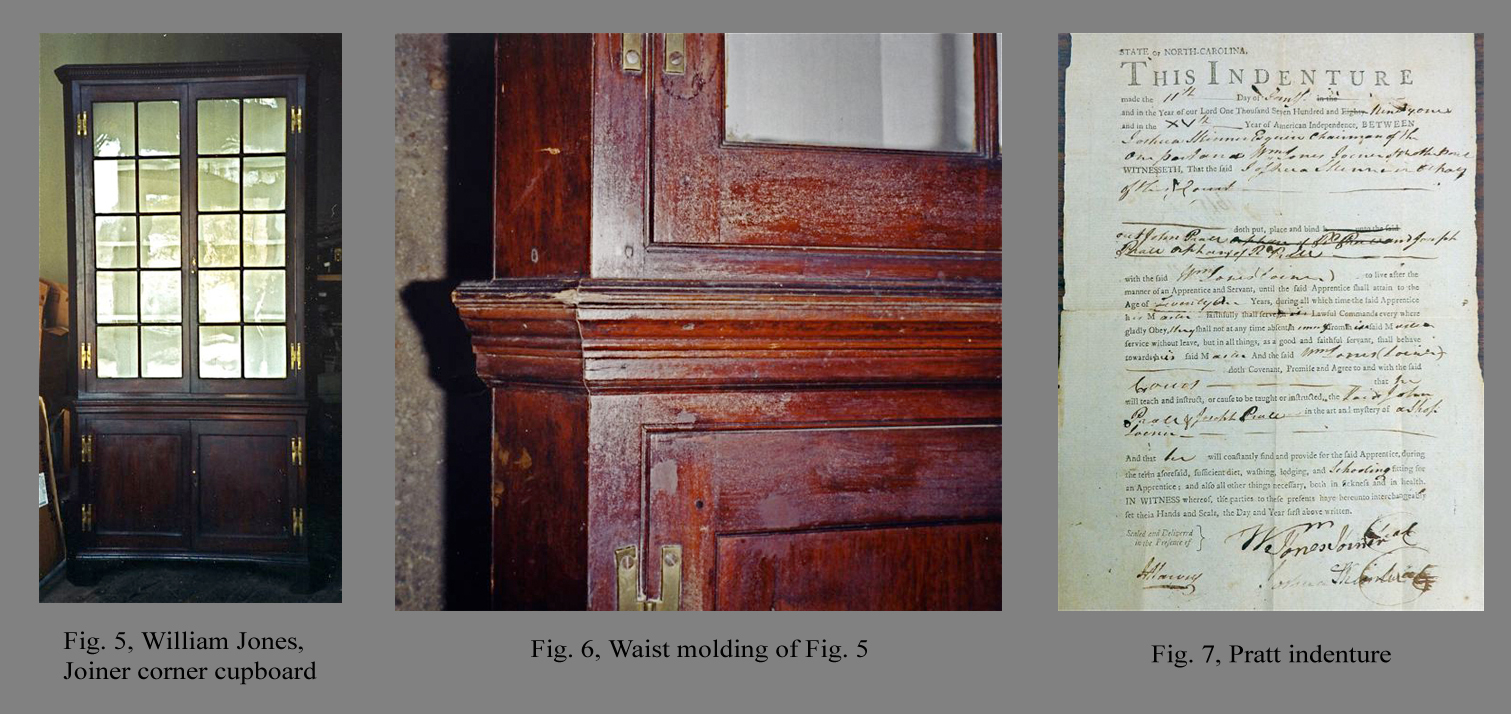

A chest of drawers that sold recently at an estate auction in northeastern North Carolina sheds new light on the cabinet shop of William Jones of Perquimans County, North Carolina through the work of one of his apprentices (Fig.1, Whedbee chest). The chest, mahogany and walnut with yellow pine and poplar secondary woods, is signed “Suttons Creek/ Joshua S Whedbee” on its interior backboards (Fig. 2, Signature on Fig.1). A further inscription on the interior of the uppermost backboard reads “June the 26 Day 1807 This 1807” (Fig. 3, Inscription on Fig.1). Whedbee became Jones’ apprentice in 1803 to learn the cabinetmaker’s trade.1

Joshua Whedbee was the son of Seth Whedbee and the grandson of Thomas Whedbee. Thomas Whedbee was a prominent landowner in the Durant’s Neck section of Perquimans County, a peninsula bounded on the west by the Perquimans River and on the east by the Little River (Fig. 4, Albemarle region, A on map). He owned 919 acres of land and 16 slaves in 1798. Thomas’ land was located near Sutton’s Creek (see Fig. 4, G on map), which flows from the Perquimans River into Durant’s Neck one third of the way down the peninsula towards the Albemarle Sound. Seth died young, leaving two children, Joshua and his brother, Thomas. These two grandchildren inherited Seth’s share of Thomas Whedbee’s Sutton’s Creek property upon Thomas’ death in late 1807, the same year the newly discovered chest was made.2

The first question in any discussion about William Jones’ cabinet shop is who exactly was William Jones. The number of Jones families residing in Perquimans and surrounding counties during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the repeated use of the popular given name, William, have made it difficult to identify this craftsman with certainty. An earlier premise was that a related Perquimans County furniture group was made by a William Jones who apprenticed to cabinetmaker and riding chair maker, Charles Moore, Jr., on April 11, 1780 to learn the “cabinet joiner’s” trade. It was felt that this William Jones and his various apprentices continued to make furniture until the first decade of the nineteenth century, when he disappeared from the written record.

The earliest of the numerous William Joneses of Perquimans County relevant to this study was the son of Thomas Jones. Thomas, who died in 1788, was the son of Peter Jones and the brother of Zephaniah and Malichi. Zephaniah also had a son named William Jones. Zephaniah died around 1762. His widow, Ann, eventually remarried Zephaniah’s nephew, William Jones, the son of Thomas.3 Ann therefore brought her son, William, in the household of her new husband, William. This created the need to distinguish these two William Joneses in court records and legal documents. William, the husband of Ann, was referred to as William Jones, Sr. William, the son of Ann, came to be called William Jones, Jr., in spite of the fact that he was not the natural son of William Jones, Sr. These delineations first occur in Perquimans County tax lists of the late 1780’s, as well as in the census of 1790. These same documents list a third William Jones. Probably a relative of the other two William Joneses, this William was listed as William Jones, Joiner.4 This individual was the former apprentice of Charles Moore, Jr.

William Jones, Sr. died in 1794. An inventory of his estate, taken by William White and Joshua Skinner, was proved on November 11, 1794. It illustrates the holdings of a middling planter of the period and included two Negroes, three beds and furniture, one desk, “one braufut and the furniture”, two looking glasses, nine flag bottom chairs, one walnut table, one tea chest, one couch, and one case and nine bottles. Listed livestock included two horses, ten head of cattle, four sheep, and forty-five hogs. William Jones, Sr. also was involved in a woodworking trade, probably house carpentry. His estate included two crosscut saws, three other saws, several lots of planes, three augers, several lots of chisels, two axes, and a “Tool Chest and trumpery in it”.5 This is probably the individual who took Joseph Barrow, orphan of William Barrow, as an apprentice in the house carpenter’s trade on January 17, 1775. Josiah Jones, a son of William Jones, Sr., was also a carpenter. Josiah took Richard Mullen, orphan of Richard Mullen, as an apprentice in the house carpenter’s and joiner’s trades on November 12, 1811.6 Deeds relating to William Jones, Jr. end in 1791, probably indicating that he left the area, or more likely that he had died. William Jones, Joiner died in 1795. An inventory of his property was taken on February 11, 1795. It has been queried whether this inventory and the inventory of William Jones, Sr. are actually two lists from the same estate. An examination of the two inventories clearly shows they each represent the holdings of a separate individual. Each lists the individual’s livestock, household furniture, and tools. Both inventories also contain identical items usually represented by a single example in households of this period. The estate of William Jones, Joiner illustrates the holdings of a simple craftsman who was less affluent than William Jones, Sr. William Jones, Joiner’s estate contained only two hogs, compared to the substantial livestock holdings listed in William Jones, Sr.’s estate. William Jones, Joiner’s Spartan household furnishings consisted of one feather bed and furniture, two flag bottom chairs, one table, one chest, three plates, six cups and saucers, a loom, and one case and bottles. His tools included one handsaw, four narrow chisels, one adze, a few planes, a few gouges, one turning gouge and chisel, and a hammer. Part of his estate had been “Taken By Mr. John Skinner and Sold for the Rent of the Land”. John Skinner was a member of the state Senate and the first federal marshal for the district of North Carolina. This land was probably in the town of Hertford (see Fig. 4, D on map) and was probably used by Jones for his shop. Hertford is the county seat of Perquimans County and is located at the narrows of the Perquimans River. Skinner also lived in Hertford. A second lot of Jones’ estate, which included most of his tools, was sold to settle a debt owed to William Roberts.7 The only other William Jones found in Perquimans County records during this period was a wealth planter who married Parthenia Newby, the daughter of Francis Newby, in 1807. This William was delineated in county records as William Jones, Esq. In 1813, he owned 670 acres, three lots in Hertford, and eight slaves.8 There is no evidence that this individual had any involvement in the house joiner or cabinetmaker trades.

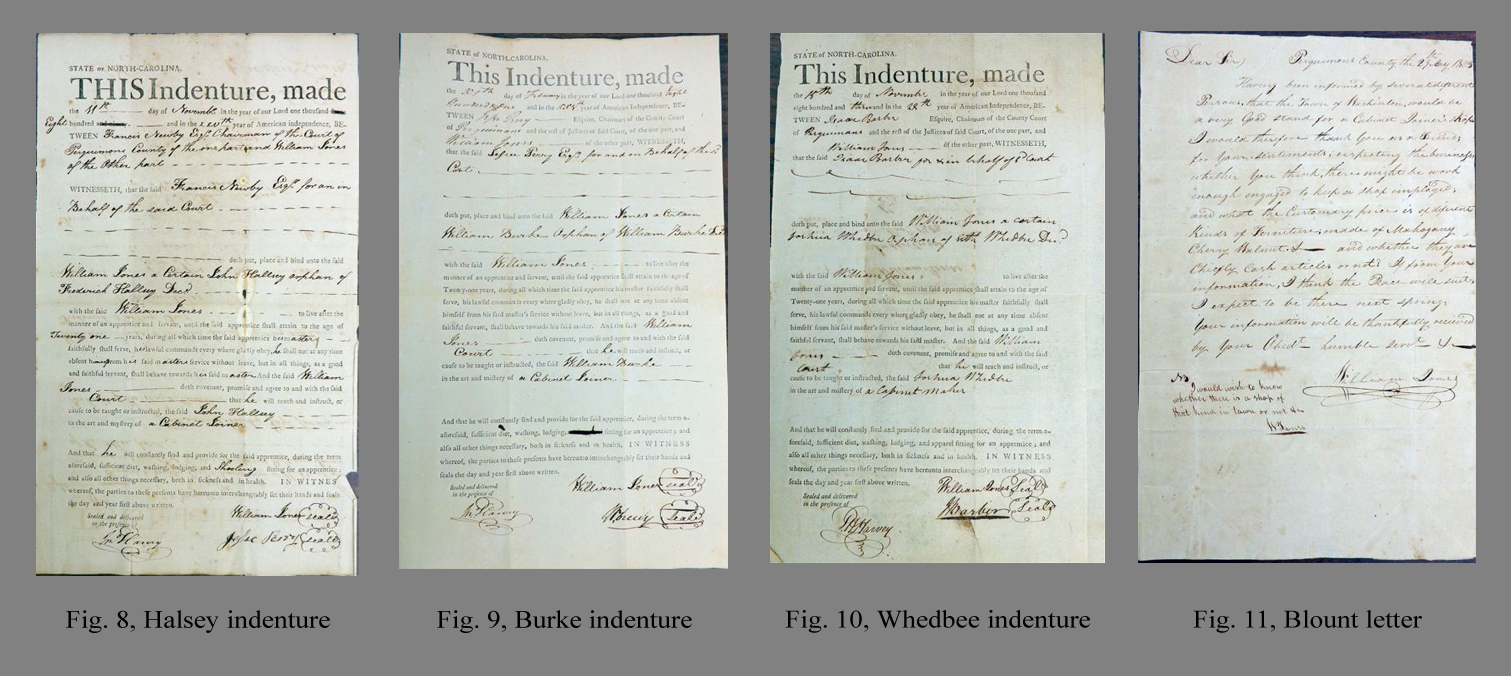

William Jones, Joiner, of the 1790 Perquimans County census, would have been free of his apprenticeship to Charles Moore, Jr. in the mid 1780’s. A corner cupboard with the painted inscriptions “E. Moore” and “W. Jones” on the back in block print represents the work of this artisan. It descended in the family of Charles Moore, Jr.9 A second matching corner cupboard was discovered in the town of Hertford10 (Fig. 5, William Jones, Joiner corner cupboard). Evidence remains of its now lost pediment, and its waist molding and base molding exactly match those found on the signed Jones cupboard (Fig. 6, Waist molding of Fig. 5). Information needed to compile tax lists and census records of the period often was gathered by individuals going door-to-door and farm-to-farm. The Perquimans County tax list of 1788 lists William Jones, Joiner, with no land, just above Charles Moore, Jr., with sixty-five acres of land.11 This is evidence that even after becoming an independent craftsman, for at least some period of time, Jones continued to live beside Moore in the “district below Skinner’s Bridge”. Jones took two apprentices “in the art and mystery of shop joiner” on January 11, 1791. They were John and Joseph Pratt, orphans of brick mason, Richard Pratt, who worked in both Perquimans and Chowan Counties (Fig. 7, Pratt indenture). No other apprentices were taken under the name William Jones until 1800, when three individuals were taken in the next three years.12 This gap is now explained by the fact that William Jones, Joiner died in 1795, so the three apprentices taken after 1800 apprenticed to another William Jones. So the question becomes, who was the second William Jones?

The answer is found in the will of prominent Perquimans County builder Henry Pointer. Written in 1800, the will contains a gift of 100 silver dollars, a substantial sum at that time, to William Jones, his former wife’s son. Jones also received a Negro boy, Terry. Pointer left the remainder of his estate to his only natural child, Jane Swepson Pointer. If Jane died, the remainder of Pointer’s estate was to be divided between Jones and Ann Enos, who was the daughter of Pointer’s sister, the wife of Lewis Enos of Gloucester, Virginia.13 William Jones, his former wife’s son and not his natural child, was a person of importance to Henry Pointer.

This William Jones was the son of William Jones and his wife, Grizzelle Swepson, who were married on September 3, 1776. Their son, William, was born on January 21, 1779. William, the father, died, and on March 2, 1783, Grizzelle married Henry Pointer, bringing four year old William into Pointer’s household. Henry and Grizzelle’s only surviving child, Jane, was born on May 23, 1790. Grizzelle died on Feburary 15, 1794, making young William, Henry’s former wife’s son for purposes of his will of 1800.14 Although a few Pointer families resided in Perquimans and Pasquotank Counties during this time, most Pointer family members lived in southeastern Virginia. The Swepsons were a southside Virginia family. Thomas Swepson, of Suffolk, Virginia, was one of the executors of Henry Pointer’s will and was referred to in the will as a relative. Swepson was a prominent citizen in Suffolk, where he served as Deputy Clerk of Nansemond County in the early 1780’s. The number of Pointer’s Virginia connections, including his sister in Gloucester, is compelling evidence that all these individuals were Virginia natives.

Pointer undoubtedly trained his stepson, William, as a woodworker. As has been shown in prior research on Robert Walker, William Buckland, and William Seay, house joiners and cabinetmakers often worked in tandem to satisfy the needs of their clients. In this case, stepson, William, undoubtedly functioned in the cabinetmaker’s role. Pointer’s estate contained an extensive assortment of woodworking tools and supplies. His estate was sold over two days, December 4, 1800 and January 31, 1801. Eighty-six planes were sold, including “cornish”, rabbet, plow, tonguing, grooving, jack, rounding, molding, fore, smoothing, and plough, as well as four bench planes. Also sold were numerous lots of chisels, adzes, augers, compasses, gouges, squares, two flooring dogs, and a diamond for cutting glass. A variety of saws were sold, including hand, whip, tenon, joiner, and crosscut. Pointer also may have produced or repaired riding chairs. These sales included a set of chair springs, a chair body, a set of cart-wheel boxes, and a pair of chair wheels.15 Pointer took several Perquimans County youths as apprentices. On May 9, 1796, he took Richard Sanders, orphan of John Sanders, as an apprentice in the carpenter’s and joiner’s trades. On February 14, 1798, he took Benjamin Sanders, orphan of Benjamin Sanders, as an apprentice in the house carpenter’s trade. Jonathan Arnold, orphan of William Arnold, was bound to Pointer on August 13, 1799 to learn the art and mystery of a house carpenter. George Augustus Harvey, orphan of William Harvey, was bound to Pointer as an apprentice in the house carpenter’s trade on May 13, 1800. A Negro boy, Wilcom or Buncomb, was bound to Pointer on June 18, 1800 as a house carpenter’s apprentice.16

Prominent house joiners often moved from place to place in search of affluent clients. William Seay built substantial homes for planters in at least four counties along the Roanoke River within a twenty-five mile radius of Roxobel in Bertie County. Henry Pointer’s career seems to have followed a similar course. Henry Pointer, Sr. and Henry Pointer are cited in the Gloucester County tax list of 1782, along with several other members of the extended Pointer Family. Henry Pointer, Sr. had 630 acres of land and eight slaves. Henry Pointer had no land but had a sizable potential work force of thirteen slaves. Both Pointer and his brother in law, Lewis Enos, are listed as residents of Ware Parish. Pointer was still conducting business in Gloucester County as late as 1784. Documents from the September 1789 session of court in Northampton County, North Carolina note that Henry Pointer and others paid expenses for individuals traveling from Dobbs County, North Carolina and Mecklenburg County, Virginia. In July 1791, John Granbury sold Henry Pointer six acres southeast of Suffolk. Pointer also owned several lots in Suffolk.17 On February 9, 1793, Pointer placed a notice in the Edenton paper addressed to the inhabitants of the District of Edenton. He explained that he had entered into an agreement with the appointed Commissioners to repair the Edenton Courthouse. He stated the Commissioners were unable to pay the agreed upon price for the work and that he considered the contract broken.18 Pointer witnessed a deed between Arrington Bolt and Nancy Turner of Halifax County, North Carolina on March 3, 1799. Despite his travels, Perquimans County seems to have been Pointer’s primary residence after 1790. That year’s census lists his household with four white males sixteen years of age and older, three white males under sixteen, four white females, one free black, and ten slaves, again giving him a sizable potential workforce. The Perquimans County tax list of 1798 lists Pointer as a resident of the Little River district (see Fig. 4, H on map) in the eastern section of the county with no land, one free white poll, and four black polls.

William Jones appears to have worked within the Pointer household until Pointer’s death in 1800. At that time, Jones struck out on his own. Pointer’s will was written on October 6, 1800 and was presented during the November term of Perquimans County court, so Pointer died between mid October and late November 1800. Jones took his first apprentice at exactly the same time. On November 11, 1800, he took John Halsey, orphan of Fredrick Halsey, as an apprentice in the cabinet joiner’s trade (Fig. 8, Halsey indenture). He took William Burke, orphan of William Burke, as an apprentice cabinet joiner on February 11, 1801 (Fig. 9, Burke indenture). Joshua Whedbee, orphan of Seth Whedbee and the maker of the newly discovered chest of drawers, was taken by Jones as an apprentice in the cabinetmaker’s trade on November 15, 1803 (Fig. 10, Whedbee indenture). Around the time of the Whedbee indenture, Jones was contemplating moving from Perquimans County. As a young man trying to make his way in the world, Jones was looking for a thriving river port with a ready market for cabinet ware but without excessive competition from other shops. Edenton (see Fig. 4, C on map) supported several substantial cabinet shops in the early nineteenth century, including those of Thomas Hankins, William Manning, at one time Hankin’s partner, and William Rombough. On May 29, 1803, Jones wrote a letter to John Gray Blount inquiring about the prospects for a young cabinetmaker in the town of Washington in Beaufort County (Fig. 11, Blount letter). Jones asked whether other cabinet shops were located in Washington and whether Blount felt there was enough demand to keep a shop engaged. Jones also was interested in prices charged in Washington for furniture constructed of various woods, including mahogany, cherry, and walnut, undoubtedly to compare to prices he charged for like work in Perquimans County.19 No reply from Blount has been located.

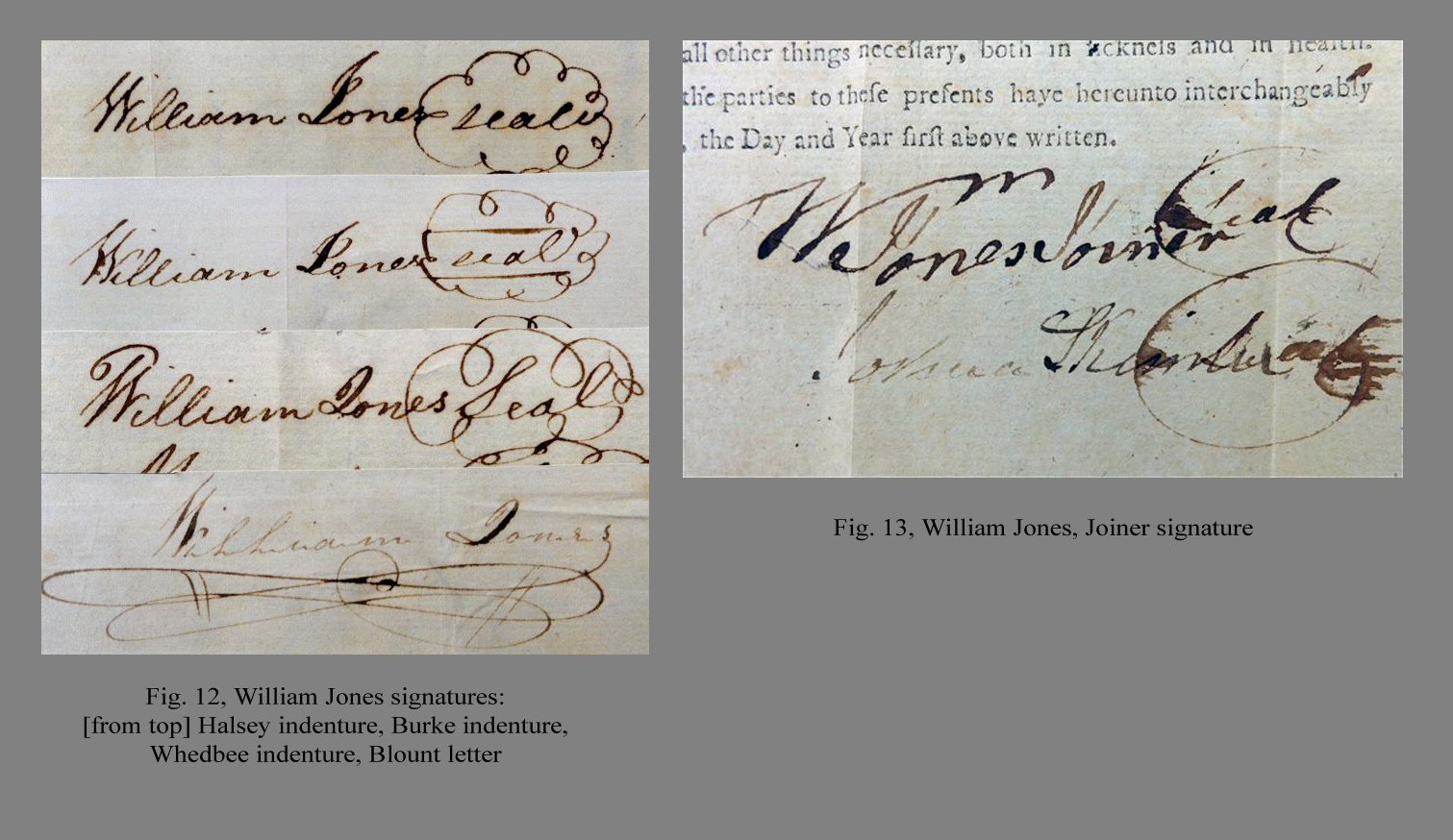

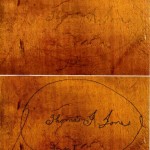

Handwriting is a useful tool in the identification of cabinetmakers and other artisans. The indentures of all three of his apprentices as well as the Blount letter carry the signature of William Jones (Fig. 12, William Jones signatures: [from top] Halsey indenture, Burke indenture, Whedbee indenture, Blount letter). The Blount letter is written entirely in Jones’ hand. Jones’ handwriting is consistent throughout these documents except for his formation of a capital “J”. In the Halsey indenture of 1800 and the Burke indenture of 1801, the top of the capitol “J” is very pointed. Jones used the same pointed “J” when he signed the bottom of a mahogany dining table in 1801, which is illustrated on page 213 in John Bivin’s The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700–1820. However, on Joshua Whedbee’s indenture and in the Blount letter, both written in 1803, Jones formed a rounded capital “J”, almost in the form of a “2”. Other distinctive letters, such as the capital “W” in William and the capital “C” in cabinetmaker, are consistent throughout all these documents. Jones actually filled out the entire Halsey indenture himself and all but the top portion of the Burke indenture, while the Whedbee indenture is in another hand.

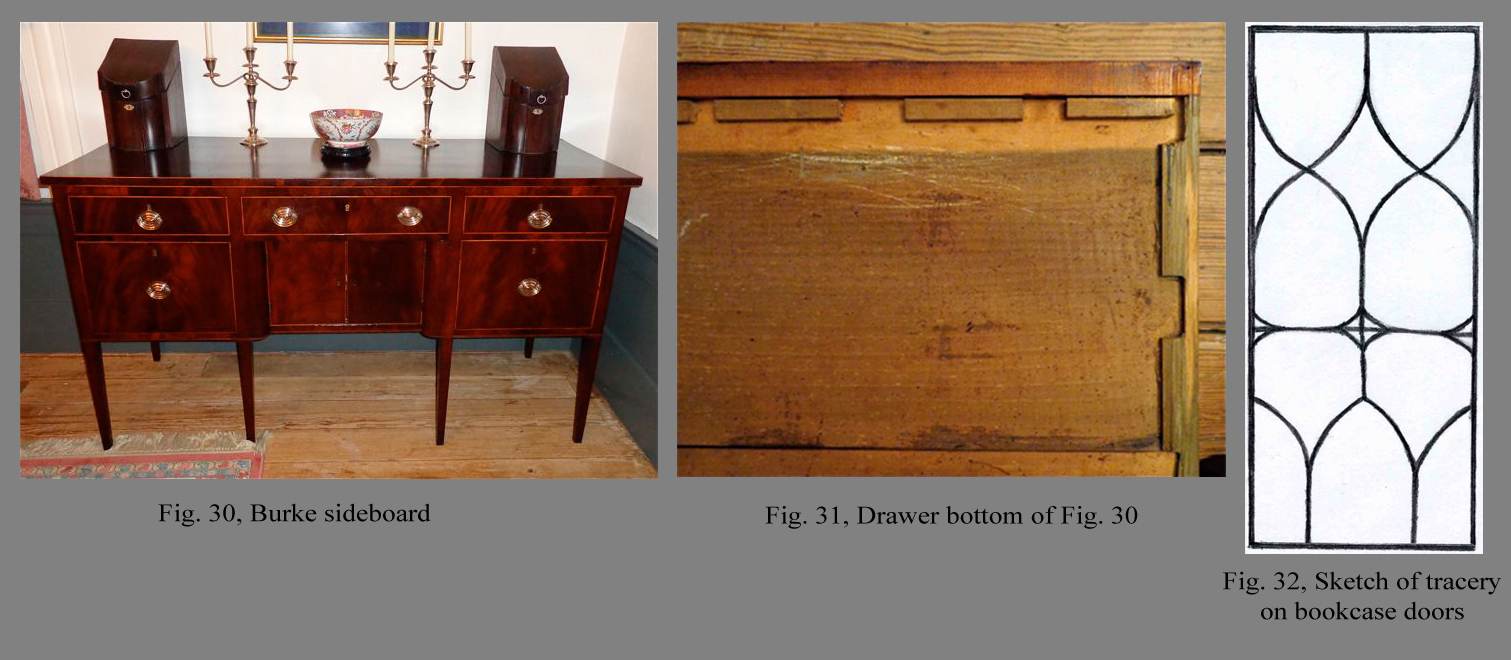

The handwriting of William Jones, Joiner is found on the indenture of his apprentices John and Joseph Pratt (Fig. 13, William Jones, Joiner signature). It is distinguished easily from the handwriting of William Jones, the stepson of Henry Pointer. William Jones, Joiner signed “Wm.” to signify his given name, William, with the “m” raised and extended over a portion of his last name, Jones. He actually filled out the entire Pratt indenture, and his handwriting is not as neat nor are the letters formed as uniformly as the handwriting of William Jones, Pointer’s stepson.

On March 18, 1805, William Jones purchased a number of cabinetmaking tools at the Pasquotank County estate sale of cabinetmaker Joseph Chamberlain. Chamberlain probably plied his trade in Nixonton, a small commercial port on the east side of the Little River (see Fig. 4, E on map). Known Nixonton cabinetmaker, Isaac Coleman, and John Lane, who in 1796 had served as executor of the estate of Nixonton cabinetmaker, Thomas Madren, were two of the purchasers at the Chamberlain estate sale. Jones’ purchase of chisels, a screw driver, a screw auger, ring screws for looking glasses, and a diamond for cutting glass is the first piece of evidence that he had decided on Nixonton as the new site of his cabinetmaker’s shop.20

Nixonton was laid out in 1746 on the property of Zachariah Nixon at Windmill Point. It was incorporated in 1758 and remained the only incorporated town in Pasquotank County until Elizabeth City (see Fig. 4, F on map), first called Redding, was chartered in 1793. Although Nixonton never attained great size, its importance as a trade and political center grew. On September 23, 1785, Nixonton became the county seat of Pasquotank County with the opening of the new courthouse, a status it maintained until the county seat was moved to Elizabeth City in 1799. In 1761, the town trustees granted “one lot or half acre of land” to Saint John’s parish. Stores, warehouses, residences, and shops made up the town. Several cabinetmakers worked in Nixonton, including Coleman, Madren, and Madren’s partner, Samuel Shakespear. By 1789, the town contained seventy residents and twenty dwelling houses.21 One of these dwellings, the Pendleton house, still remains in Nixonton, though now moved to a different site in town (Fig. 14, Pendleton house, Nixonton). It probably is representative of the houses in Nixonton in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The port of Nixonton was a natural choice for Jones. It is located in far-western Pasquotank County, and it is only a few miles from the Little River district of Perquimans County, Henry Pointer’s residence and therefore probably Jones’ residence. Pasquotank County would have appealed to an enterprising young cabinetmaker in 1805. The Dismal Swamp Canal had just opened connecting Norfolk to the Albemarle region. Completed sections on the northern and southern ends of the canal were connected by a road as the digging of the central section of the canal continued. In 1805, Elizabeth City, the southern terminus of the canal, was still a fledgling community. A few ordinaries and a merchandise store comprised its business district. Real growth took place after the canal channel was deepened in 1828.22 Consequently, Nixonton was the closest substantial Albemarle port to the canal. Jones would have been familiar with the progress of the canal. Thomas Swepson, Henry Pointer’s executor, was Customs Collector of the Port of Suffolk. He was also elected as a Manager of the Dismal Swamp Canal Company in April 1797 upon the death of his father-in-law, John Driver.

William Jones formed a personal as well as a business relation with Nixonton cabinetmaker, Isaac Coleman. On September 2, 1808, Jones married Mary Coleman, in what appears to have been a second marriage for Jones.23 Mary is believed to have been Isaac’s sister. They are thought to be the children of Charles and Peggy Coleman of Nixonton. In 1787, Peggy purchased lot 63 in Nixonton at a sheriff’s sale after Charles had lost it to debts. Isaac apparently inherited this lot along with lot 64, for he sold them to Gabriel Bailey on August 3, 1812.24 Isaac Coleman and William Jones were also business partners. They jointly owned Nixonton lots 52 and 53. They may have been in partnership in a jointly-owned cabinet shop, or they might have maintained separate shops on these adjacent lots. They sold the two lots to Hannibal Swann on September 9, 1812.25 Coleman was experiencing financial difficulties in the early 1810’s. On July 1, 1811, he obtained a loan from John Pool for $350.00. The loan was secured by a bill of sales for most of the remaining property Coleman owned, including his residence “and all my working tools”, twenty hogs, two cows, one horse, seven feather beds and furniture, “all my household and kitchen furniture too tedious to mention”, and four other Nixonton lots. He was unable to repay the loan, and the bill of sales was exhibited and proved in the June 1813 term of Pasquotank County court.26 No other references relating to Coleman have been found. William Jones died in 1815 in Pasquotank County. On March 7, 1815, his orphans, William, age 16, and James, age 14, were apprenticed to Zadock Forbes to learn the house carpenter’s trade, Henry Pointer’s former profession.27

Several pieces of furniture attributed to William Jones’ cabinet shop are documented in the files of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. A walnut fall-front desk with yellow pine and poplar secondary woods was constructed with wrought nails and probably represents Jones’ early work before Pointer’s death in 1800. Its interior has two drawers over one drawer under four pigeonholes on either side of a prospect door flanked by reeded document drawers. The desk was purchased from the Lane family of Harvey’s Point on the lower end of Harvey’s Neck (see Fig. 4, B on map). Harvey’s Neck is a peninsula in Perquimans County on the west side of the Perquimans River. The desk exhibits construction features found throughout the work of Jones and his apprentices. The exterior drawers contain flush beading around their outer edges. The drawer bottoms are dadoed into the drawer fronts and sides and flush nailed to the drawer backs. Spaced glue blocks add further support to the front and sides of each drawer bottom. The case bottom is supported by continuous walnut base blocks, with integral base molding, along the front and sides. The back edge of the case bottom is supported by a single base block approximately eight inches long extending from each rear corner. Square vertical blocks flanked by shaped horizontal blocks support the bracket feet and the rear foot supports.28

A cherry chest with yellow pine secondary wood has bracket feet that match those of the previous desk. This chest has no recovery history, but it was signed by both William Burke and Joshua Whedbee while they were apprentices in Jones’ shop. Based on the dates they apprenticed to Jones and the year Jones is found in Pasquotank County, the chest must date between 1803 and 1805. In our research experience, apprentices signing work in a master’s shop is highly unusual. Normally, apprentices would have signed the master’s name. This example clearly shows that all rules are not hard and fast. The drawers of this chest are supported by drawer runners dadoed into the case sides, as opposed to the full dust boards found on the previous desk. The bottom of the chest is supported by continuous walnut base blocks, with integral base molding, along the front and sides, with short base blocks in the rear. Blocks supporting the bracket feet exactly match those found on the previous desk, although the chest’s horizontal blocks are unshaped. The case’s lower front corners are mitered. The chest’s drawers exhibit flush beading and are supported by spaced blocks along the front and sides of each drawer bottom. The drawers contain unusually large, though well executed, dovetails of matching size at the front and rear corners. The signatures are found on the interior of the case backboards, the same location as the writing on the newly discovered Whedbee chest. On the upper backboard is written “Bureau Back J Whe”. On the lower backboard is written “William Burke Esq cab”.29 The writing is truncated, so was placed on the boards before they were cut and attached to the case. “J Whe” appears to be in Whedbee’s hand, while the rest appears to be in Burke’s handwriting.

A second cherry chest, with yellow pine and poplar secondary woods, is supported by straight feet slightly flared at the bottom, which are set flush with the case. These feet are usually termed French feet and match the feet found on the newly discovered Whedbee chest. Unusually wide three-part banding, again matching the banding of the new Whedbee chest, is set along the lower edge of the chest’s case. The intricate top molding found on this chest exactly matches the top molding of the previous chest. This chest descended in the Nixon family of Hertford and probably dates to the same time period as the previous chest. Its drawer construction, including dovetails, exactly matches the drawer construction of the previous chest, with flush beading around each drawer and spaced glue blocks supporting the fronts and sides of the drawer bottoms. The drawer runners are set in dadoes in the case sides.30

A walnut chest with yellow pine and poplar secondary woods made by William Jones or his apprentices descended in the Wood family of Greenfield plantation (Fig. 15, Greenfield Chest). Greenfield is located in eastern Chowan County near the mouth of the Yeopim River (see Fig. 4, I on map). This chest has a thick, one-board top with applied molding matching the molding of the previously discussed chests (Fig. 16, Top of Fig. 15). The sides are half dovetailed to the walnut top and the yellow-pine bottom boards. The continuous walnut base blocks, with integral base molding, mitered lower front case corners, and vertical foot blocks flanked by shaped and unshaped horizontal blocks are standard Jones fare (Fig. 17, Base and foot blocks of Fig. 15). The base blocks are secured to the bottom of the case with cut nails with hand-forged heads, countersunk into funnel shaped holes (Fig. 18, Countersunk base block nails of Fig. 15). This unusual construction feature also is found on the chest signed by Burke and Whedbee and serves as a signature of the work of this shop. Spaced blocks support the drawer bottoms, and the drawers display standard Jones shop dovetailing (Fig. 19, Drawer blocks of Fig. 15)(Fig. 20, Drawer dovetails of Fig. 15). A subtle, slightly serpentine mark was used by the maker of this chest to denote the interior surface of the drawer sides (Fig. 21, Serpentine mark in drawers on Fig. 15).

The inscription on the newly discovered chest by Joshua Whedbee (see Figs. 1, 2 & 3) shows that he had returned to his home at Sutton’s Creek by 1807. He, therefore, was no longer working in William Jones’ cabinet shop. Apprenticeships normally lasted for seven years, though some were specified for shorter terms.31 Whedbee’s apprenticeship began in November 1803, so only three and one-half years had passed when he made this chest. The apprenticeship probably ended when Jones left Perquimans County, although Whedbee could have accompanied Jones to Pasquotank County and spoken free of his indenture there. Joshua Whedbee died in Perquimans County in 1834. By that time, he had sold the land he had inherited. It is not known how long he continued to produce furniture.

The chest’s construction demonstrates that Whedbee continued many of the practices learned in Jones’ shop but that others were modified by Whedbee once he was free of his apprenticeship. It has solid mahogany sides and mahogany veneered drawer fronts, with a solid walnut top. The chest’s drawer bottoms are supported by spaced glue blocks in the normal manner of Jones’ shop (Fig. 22, Drawer bottom of Fig. 1). The drawers also display the same large dovetails found on the previous Jones shop examples (Fig. 23, Drawer dovetails of Fig. 1), and the case also contains drawer supports dadoed into the case sides (Fig. 24, Case interior of Fig. 1). This chest’s top molding exactly matches the top moldings on the chest signed by Burke and Whedbee, the cherry chest with French feet, and the Wood family (Greenfield) chest. The lower front corners of the case are mitered, as is seen on the chest signed by Burke and Whedbee and the Wood family chest. Whedbee also continued the use of more stylish French feet set flush with the case and wide three-part banding along the lower case. The case itself is supported by continuous base blocks under the case front and sides with short base blocks under the rear of the case, again attached with nails countersunk into funnel-shaped holes. The French feet are backed by vertical blocks flanked by horizontal blocks, matching the signed Burke-Whedbee chest. Here, however, the vertical blocks are rounded to prevent them from being seen (Fig. 25, Base blocks and foot blocks of Fig. 1).

Various construction and assembly marks are also found on this chest. The word “back” is written on the back of each of the drawers (Fig. 26, Writing on drawers of Fig. 1). The handwriting almost exactly matches William Burke’s handwriting on the interior of the backboards of the chest signed by he and Whedbee. This similarity should come as no surprise. Apprentices often were taught to read and write by their masters, in this case William Jones. Jones actually added the word “shooling” (sp) to his list of responsibilities on John Halsey’s indenture. There are, however, slight differences in the handwriting of Burke and Whedbee. Whedbee formed his “c” in the word “back” with a loop, making the “c” look like an “e”. Burke formed the “c” in the word “back” more traditionally without a loop, as is illustrated on page 215 of Bivin’s The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700–1820. Whedbee placed his initials on the bottom of the 1807 chest (Fig.27, Whedbee’s initials on bottom of Fig. 1). He also used a board that later became a drawer bottom to design the teardrop escutcheons found on this chest. “2 boxes and __ glasses” is written on the top of the board that became the chest’s bottom. A further construction notation, “1 wide 4”, is found on the top of the same board. It references the size of a particular piece of wood for this chest or another piece made by Whedbee around this time. Similar notations are found on the interior backboard of a sideboard made by Bertie County house joiner and cabinetmaker, William Seay.

The construction of the top of this chest deviates from the work Whedbee had done in Jones’ shop. The single-board, walnut top is supported by four battens set front to back. The two center battens are thinner than the side battens, with the grain of the wood running from front to back. The two end battens are composed of several three to four-inch wide pieces of wood with their grain running side-to-side or parallel to the grain of the top board of the chest (Fig. 28, Top support structure of Fig. 1). This allows the end battens to expand and contract with the top board as temperature and humidity fluctuate, reducing the risk of the top board splitting. All four battens protrude through the top backboard of the chest (Fig. 29, Back of Fig. 1). The top structure is supported by blocks glued to the upper case sides and a rail set across the front of the chest.

By late 1805, William Burke was living in Edenton; further evidence that all apprenticeships ended when Jones moved to Pasquotank County. On November 22 of that year, Burke, perhaps as a result of time spent at O’Malley’s tavern next door, “…did then and there wickedly and willfully break down and destroy the main door of the large room in the upper apartment on the Court House in Edenton….”. The charge lists Burke as a “Boat Builder”.32 In 1805, Edenton was the main commercial port of the Albemarle region, so building and repairing ships was a major source of revenue for skilled woodworkers. Edenton cabinetmakers, such as William Rombough and Samuel Black, often supplemented their income by block making and other ship related construction activities. In 1808, Burke apparently reemphasized his cabinetmaking background. He bought a number of cabinetmaking tools in the April estate sale of Edenton cabinetmaker, Thomas Hankins. His purchases included fourteen molding planes, one saw, one lot of chisels, four planes, and one lot of patterns.33

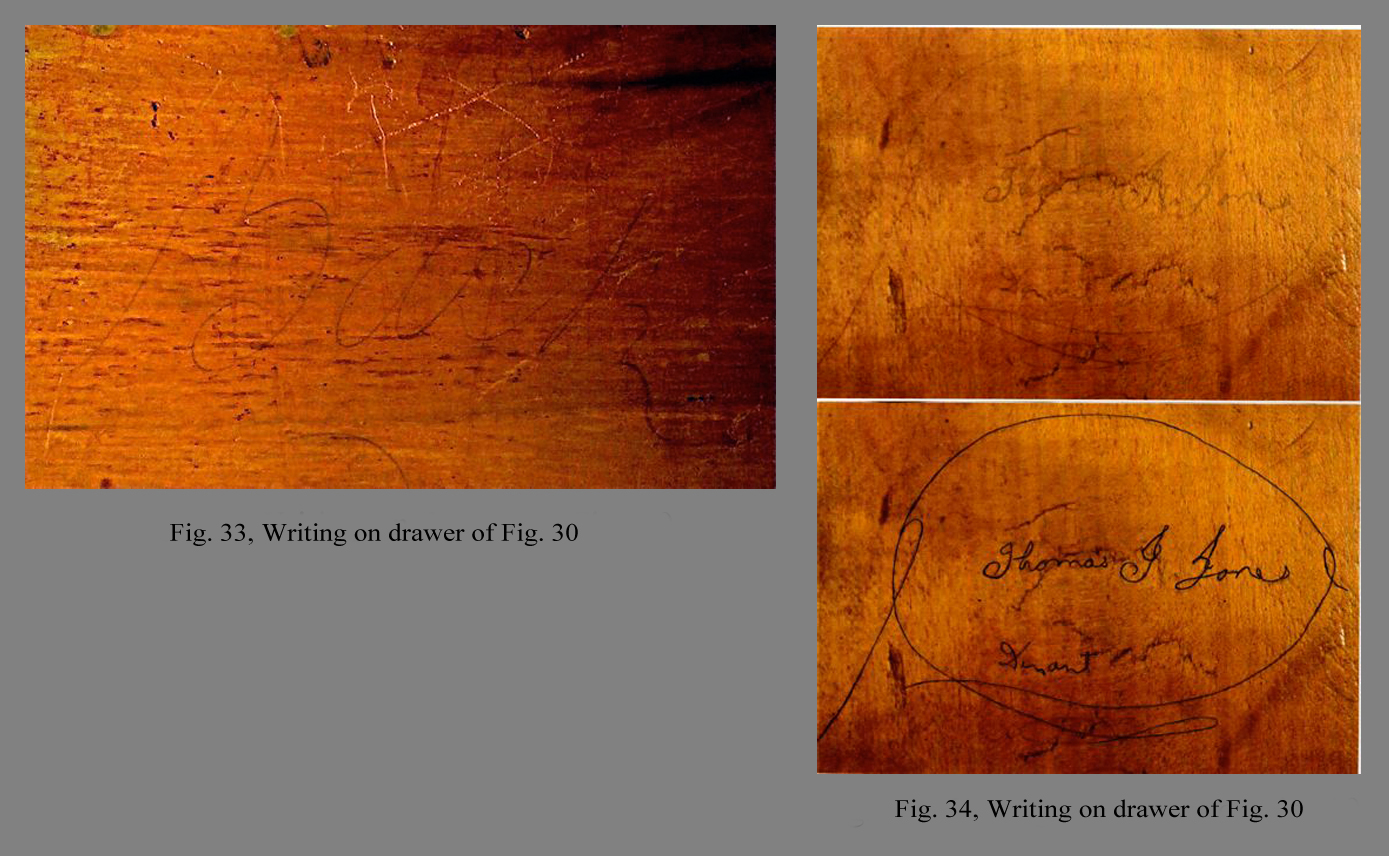

A mahogany sideboard by Burke probably was built shortly after the Hankin’s sale (Fig. 30, Burke sideboard). Its construction reflects Burke’s training in Jones’ shop, but it also demonstrates his desire to make furniture to compete in the Edenton market. The sideboard’s drawers are supported by runners dadoed into the case sides. Burke supported the drawer bottoms with spaced glue blocks along the drawer fronts and sides, just as he had done in Jones’ shop (Fig. 31, Drawer bottom of Fig. 30). The drawer dovetails are narrow and elongated in the front and shorter in the back, a standard feature of Norfolk furniture of the period, although these dovetails are not of the quality found on Norfolk products. Edenton cabinetmakers had been heavily influenced by Norfolk cabinetmakers and their wares since colonial times. Norfolk was the major deep-water port serving northeastern North Carolina and southeastern Virginia. In the early nineteenth century, Norfolk imports and Norfolk trained artisans plying their trade in Edenton set the standard by which Edenton cabinet wares were judged. Secondary woods chosen by Burke for this sideboard also exhibit Norfolk influence. While the poplar used was probably cut locally, the white pine and spruce used were imported from New England and probably transshipped from Norfolk to Edenton, as well as to other Albemarle ports. Nixonton cabinetmakers also received northern woods. A mahogany press with secretary drawer and bookcase contains the inscription “Made and Sold by Isaac Coleman, Nixonton, North Carolina, August 25, 1809” on the inner top of the secretary drawer. Its secondary woods include imported white pine and native cypress and yellow pine. The press and bookcase is completely in the Norfolk style and easily would be taken for a Norfolk product without Coleman’s inscription. The secretary drawer contains a bank of four drawers on either side of an elongated pigeonhole surmounting six standard-size pigeonholes. The front of the secretary drawer appears to be two drawers set side by side, each with oval inlay. The press doors contain round inlay surrounded by square inlay with clipped corners. Each bookcase door contains complex, curvilinear muntins whose tracery results in arches forming a central diamond pattern (Fig. 32, Sketch of tracery on bookcase doors).34 William Jones’ work during his Nixonton period probably reflects the same Norfolk influences exhibited by his future partner’s work and may have been mistaken for Norfolk products over the years.

Continuing one of the most predominant construction techniques seen in the furniture produced in Jones’ shop and afterwards by his former apprentices, Burke wrote the word “Back” on the back of the lower right drawer of the sideboard (Fig. 33, Writing on drawer of Fig. 30). It is written in the same hand as Burke’s inscription on the backboards of the chest signed by Burke and Whedbee while apprentices in Jones’ shop. A further signature, Thomas J. Jones, was written twice on the upper surface of the bottom board of the sideboard’s middle drawer. One signature is large and was written parallel to the front of the drawer. The other is small and was written perpendicular to the drawer front. Both signatures are written in the same hand. “Durant”, again in the same hand, is found below the smaller signature (Fig. 34, Writing on drawer of Fig. 30 [The upper portion of this figure is the writing as it appears in situ, while the lower portion of this figure is the same writing enhanced for clarity.]). All this writing is in a hand that is very similar to the handwriting of William Jones before 1803. Thomas was probably a brother of William and also trained by Pointer, explaining the similarity in their signatures. “Durant” undoubtedly refers to Durant’s Neck in Perquimans County, the location of Henry Pointer’s home as listed in the county’s 1798 tax list, therefore also the home of William Jones and any of his siblings.

Signed and dated examples of Southern furniture, such as the newly discovered Whedbee chest, become the foundations upon which the identification and study of Southern cabinet shops is based. We can debate style and technique, but a signature is hard to dispute. The discovery of this chest has been the catalyst for a reexamination of one element of what has been termed the “Late Perquimans School” of cabinetmaking in northeastern North Carolina.35 By examining the construction of known and newly discovered examples from this group; researching estate papers, inventories, wills, and deeds pertaining to individuals who might have been involved in the production of this furniture, and eliminating those who were not; comparing signatures and various writings found on the furniture with known examples of potential makers; and examining stylistic influences exerted on the Albemarle region during the period these pieces were created from Norfolk, the area’s major source of goods and information; we have discovered not one, but two men of the same name who were responsible of this specific furniture group. One was grounded in the late Rococo conservatism of the earlier Perquimans School, while the second was influenced by the new wave of neoclassical taste sweeping the nation, as interpreted regionally by Norfolk artisans and transmitted throughout southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. Also, as we discovered in our study of William Seay, the WH Cabinetmaker, Henry Pointer and his stepson, William Jones, are another example of the interrelationship between house joiners and cabinetmakers as they strived to create a market for their wares and as a result secure their own financial security and that of their families.

For a slideshow of all of the images used in this article, click on any of the following pictures:

- Figure 15, Greenfield Chest

Published on: Dec 11, 2012

Acknowledgements

The authors especially wish to thank Virginia Wood, Sambo Dixon, Joe Jenkins, and Don Jordan for their help in the preparation of this article.

Note: Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 “Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina”.

Endnotes

1. Perquimans County Apprentice Bonds and Records 1737-1892, Joshua Whedbee Indenture, North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, NC. (Afterwards State Archives)

2. Perquimans County Will Book E, p. 320 and State Archives, Perquimans County Tax List of 1798.

3. Perquimans County Will Book C, p. 363 and Perquimans County Deed Book I, #848.

4. State Archives, Perquimans County Tax List of 1789 and Perquimans County Census of 1790.

5. State Archives, Perquimans County Estate Records 1714-1930, estate of William Jones, Sr.

6. Dru Gatewood Haley and Raymond A. Winslow, Jr., The Historic Architecture of Perquimans County, North Carolina, The Town of Hertford, Hertford, NC, 1982, pp. 252-253.

7. State Archives, Perquimans County Estate Records 1714-1930, Estate of William Jones, Joiner.

8. State Archives, Perquimans County Tax List of 1813.

9. John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina 1700-1820, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, NC, 1988, p. 208.

10. Conversation with Joe Jenkins, August 8, 2012.

11. State Archives, Perquimans County Tax List of 1788.

12. Haley, Architecture, pp. 252-253.

13. Perquimans County Will Book E, p. 123.

14. State Archives, NC Family Research Collection, Jones-Pointer Family Bible.

15. State Archives, Perquimans County Estate Records 1714-1930, Estate of Henry Pointer.

16. Haley, Architecture, pp. 252-253.

17. Polly Cary Mason, Records of Colonial Gloucester County, Virginia, Volume 1, Clearfield Publishing, 1946, pp. 94 and 100 and Fillmore Norfleet, Suffolk in Virginia c. 1795-1840, Copyright by the Author, 1974, pp. 57 and 89.

18. Raymond Parker Fouts, Abstracts of the State Gazette of North Carolina 1787-1791, Volume 1, Gen Rec Publishing, Cocoa, FL, 1982, p. 11.

19. State Archives, John Gray Blount Papers, Letter from William Jones to John Gray Blount dated May 29, 1803.

20. Bivins, Furniture, p. 462.

21. Thomas R. Butchko, On the Shores of the Pasquotank, Museum of the Albemarle, Elizabeth City, NC, 1989, pp. 7-14 and William A. Griffin, Ante-Bellum Elizabeth City, Copyright by the Author, 1970, pp. 12, 14, 16, and 23-28.

22. Griffin, Ante-Bellum, p. 69.

23. Vincent Mercer, Pasquotank County Marriage Bonds 1741-1866, Family Research Center of Northeastern NC, Elizabeth City, NC, 2000, p. 18.

24. Pasquotank County Deed Book K, p. 177 and Book T, p. 94.

25. Pasquotank County Deed Book T, p. 70.

26. Pasquotank County Deed Book T, p. 229.

27. James H. Craig, The Arts and Crafts in North Carolina 1699-1840, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, NC, 1965, p. 337.

28. MESDA Research File S-4449.

29. MESDA Research File S-3065.

30. MESDA Research File S-3052.

31. Bivins, Furniture, p.69.

32. Marc D. Brodsky, The Courthouse at Edenton, Chowan County, Edenton, NC, 1989, p 33.

33. Bivins, Furniture, p. 459.

34. MESDA Research File-Cabinetmakers, Isaac Coleman.

35. Bivins, Furniture, p. 206.